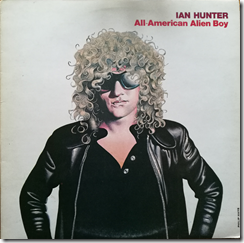

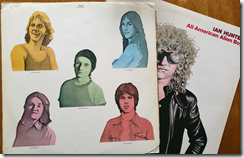

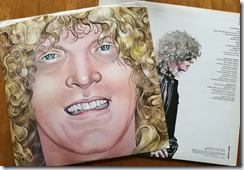

All American Alien Boy (April 1976)

CBS 81310

UK: 29 US: 177

Since a second Hunter-Ronson album was out of the question, Ian Hunter assembled a new band for his second solo album. It was an excellent one, with Jaco Pastorius on bass, Chris Stainton on piano and organ, Gerry Weems on guitar, David Sanborn on sax, and Aynsley Dunbar on drums.

The strength of this jazz-flavoured band along with Hunter’s experiences as a new resident of the USA inspired some of the most thoughtful lyrics he would ever write.

Letter to Britannia from the Union Jack is a melancholic look at his old home country, which he saw as “a victim of your history,” a nation with a glorious past but a sadly unglorious present. The backing is tuneful but sombre.

All-American Alien Boy is more up-beat, a pounding seven-minute monologue on being a “whitey from blighty”, with prominent bass from Pastorius, fine guitar work from Weems, combined with Sanborn’s sax and female backing vocals to make a collage of sound. Hunter’s singing is somewhat recessed in the mix, but full of passion and with some memorable lines, such as “up and down the M1 in some luminous yo-yo toy”, or “the women came from heaven, the men came out of some store.” One of my favourites.

Irene Wilde is a more traditional Hunter ballad, and a song he still performs. A true story, says Hunter, based on his teenage angst encountering a girl he fancied at a bus station, who made it clear that dating was out of the question. Great melody, gentle backing and a heartfelt delivery.

Restless Youth, which closes side one, is the nearest this album has to a rocker, about a troubled boy in New York who is killed by a cop. Hunter blames his fate on “politician thieves.” As a political statement it’s not convincing, but it does chime with Hunter’s general view that the kids are all right, or would be if properly treated.

Side two opens with Rape, which describes (I think) a young man who commits a rape but gets off scot free because he is “sick rich and stoned” and has a good lawyer. “Justice just is Not!” is the punning conclusion. Hunter’s mentor Bob Dylan does this sort of song better; but it is a strong number nevertheless.

Next up is You Nearly Did Me In, which remarkably has most of Queen on backing vocals. The story is that Queen (who had toured with Mott the Hoople) just happened to be visiting the studio at the right time. It’s another highlight of the album, a song possibly about drug addicts, “lost children of the night”, with a great chorus, though exactly why the narrator is nearly “done in” has never been clear to me. The close of the song is epic though. “What ever happened to dignity? What ever happened to integrity? What ever happened to honesty?” Sanborn’s alto sax is gorgeous on this song.

Apathy 83 is a kind of reprise to the song by the Stones, and according to Devine the title was handed to Hunter by none other than Bob Dylan, after what they considered a poor Stones concert at Madison Square Garden in New York. The two happened to meet soon after; Dylan asked Hunter what he thought of the Stones concert. “Insipid,” sand Hunter. Dylan replied, “yeah, apathy for the devil.”

The song takes that thought and applies it to the politics of the time; apathy is allowing evil to flourish. To my mind this is one of Hunter’s best political statements as he rants against misdeeds in high places. Nice accordion from Dominic Cortese.

The album closes with God (Take 1), a dylanesque song in which Hunter explores religion. “I wanted to let people hear how it would sound if I really imitated Bob Dylan,” said Hunter. The song is perhaps my least favourite on the album though, rather ponderous.

All American Alien Boy is distinctive in Hunter’s solo career, beautifully performed, expertly sung, lyrically thoughtful, melodic and jazz-tinged. It was well reviewed but, says Hunter, “pretty boring on one level.” It was a huge departure from the raucous energy of Mott the Hoople, much more so than the album before it. The kids couldn’t relate and sales were disappointing. “The fact that it died commercially was a total bummer,” says Hunter.

In a recent interview with Def Leppard’s Joe Elliott, the two reflect on the album. Hunter reminds us why Ronson was not on the album. “Mick was still with Tony [Defries]. Mick was going to get more than I got, so I said no,” he says.

“You put out Alien boy,” says Elliott. “I’m 16 years old, and … what are you doing? You’ve made this album for my dad. I want more of the first records. Where’s all the rockers? It’s all very clever clever.”

“By the time I was the age you were when you made that record, all of a sudden that record made sense to me,” Elliott continues. “It took 20 years but I got it. The title track is phenomenal, because not only is it an incredible delivery, like rap before rap, it’s got the most incredibly beautiful bass playing by Jaco Pastorius, absolutely stunning, but it took me years to get my head around it.”

Hunter says it was Ronson’s favourite record of his, eventually, though not at the time.

Me, I love the album, though I wish it ended with Apathy ’83.