Yesterday, SUSE and Xamarin announced, in effect, the transfer of all things Mono to Xamarin.

The agreement grants Xamarin a broad, perpetual license to all intellectual property covering Mono, MonoTouch, Mono for Android and Mono Tools for Visual Studio. Xamarin will also provide technical support to SUSE customers using Mono-based products, and assume stewardship of the Mono open source community project.

Xamarin is a startup formed by Mono founder Miguel de Icaza following the acquisition of Novell and SUSE by Attachmate, which ceased Mono development.

Attachmate acquired Novell in November 2010. Mono has been plucked from the abyss with impressive speed.

That said, the strategy behind Mono has shifted. Mono exists because de Icaza liked what Microsoft announced back in 2000 when it introduced C# and the .NET Framework. Microsoft made a show of standardizing the .NET CLI (Common Language Infrastructure), which made PR sense at the time since there was controversy over Sun’s ownership of Java, though nobody really believed that Microsoft knew how to steward an open source development platform or indeed believed that it was really serious about it. History largely justifies that scepticism; but de Icaza called Microsoft’s bluff and forged ahead with Mono, implementing not only the CLI and C# but most of the .NET Framework as well.

The goal of Mono, as I recall, was to bring the benefits of C# and .NET to Linux developers, and to enable developers to move applications freely between Windows and Linux. Apple OS X was also on the radar, though it took longer to become much use. Recalling Mono’s early days, de Icaza said:

Mono to me is a means to an end: a technology to help Linux succeed on the desktop.

Mono worked remarkably well from quite early on, but never quite well enough to persuade mainstream developers it was a sensible choice for applications that would otherwise have run on Windows. It did emerge as a viable and productive toolset and platform for Linux and a number of Mono applications became popular, including Beagle search, Tomboy notes, and F-Spot photo management. Some ASP.NET applications run on Mono; I have one on this site. Another Mono success was its use as the scripting engine in Unity, a game development platform.

A big problem for Mono though was the lack of a business model. There was support and servicing of course, which must have generated some revenue for Novell, but most Mono use is free. Novell possibly had in mind that Mono could be significant as an application server, but it has never become a really trusted platform in the Enterprise. For example, as Alan Radding (Dancing Dinosaur) notes:

DancingDinosaur has not found any SUSE on z user that has successfully implemented .NET apps on the mainframe. A few have tried but reported that Mono on z wasn’t ready for prime time.

Even among the free software and open source community, Mono was hampered by suspicion of Microsoft. If Mono became successful enough to threaten Microsoft, would lawyers appear? Given the way Microsoft is currently behaving with Android, filing legal actions and signing up licensees, those fears might not be unwarranted.

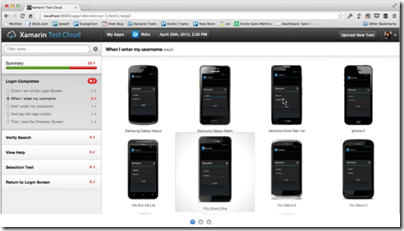

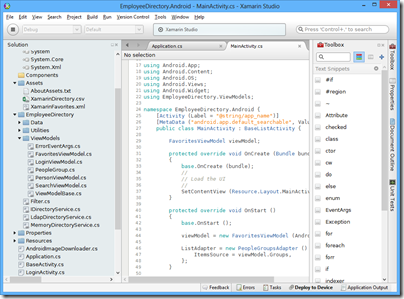

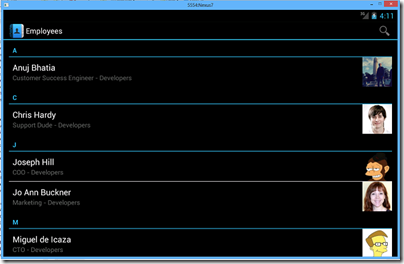

So what is Mono today? The answer is that Mono is now primarily a mobile platform. The Xamarin home page makes this clear, as well as making it apparent that the Mono team has discovered the value of a business model:

Xamarin is tapping into two real business needs. One is the need for a cross-platform mobile development platform that works. The second is a way for Windows developers to use their existing C# skills for mobile development, given that they might not be happy with the tiny market share currently achieved by Windows Phone 7.

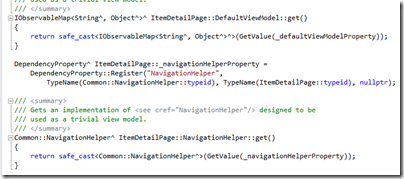

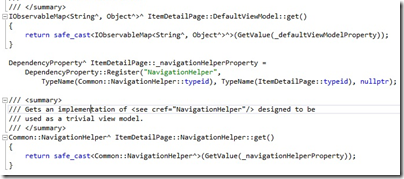

When I had a quick try with Monotouch I was impressed, and I would like to spend some more time with it and with Mono for Android.

Mono has touch competition though. In particular, PhoneGap, Appcelerator’s Titanium, and Adobe AIR. I was interested to see that Adobe is coming up with a packager for AIR on Android, which may significantly improve it as a cross-platform mobile toolkit.

Still, Xamarin is small and nimble and I expect it to succeed. It has also has Visual Studio integration, which is an advantage. One of the pieces Xamarin has now licensed from SUSE is Mono for Visual Studio.

The downside of these latest developments is that if you depend on Mono for the desktop or for ASP.NET, you may find these parts of the Mono project getting little attention from the new company. But Mobile is all that matters now, right?

I write this on July 19 2011. According to Wikipedia:

Recognizing that their small team could not expect to build and support a full product, they launched the Mono open source project, on July 19, 2001 at the O’Reilly conference.

Well, if there was a launch there it was low-key. It is not mentioned in this report. But de Icaza does recall:

We planned the announcement to come by July 19th 2001, so we could announce this at the O’Reilly conference, as Tim O’Reilly had been very supportive of this effort, and had offered his help since the early stages, when it was still a very young idea. When we announced the project launch we had our team in place, and we were shipping our metadata framework and our C# compiler as well as a few initial classes So officially the Mono project was launched on that date, but it had been brewing for a very long time.

Happy Anniversary!