Any website that supports SSL (an HTTPS connection) requires a digital certificate. Until relatively recently, obtaining a certificate meant one of two things. You could either generate your own, which works fine in terms of encrypting the traffic, but results in web browser warnings for anyone outside your organisation, because the issuing authority is not trusted. Or you could buy one from a certificate provider such as Symantec (Verisign), Comodo, Geotrust, Digicert or GoDaddy. These certificates vary in price from fairly cheap to very expensive, with the differences being opaque to many users.

Let’s Encrypt is a project of the Internet Security Research Group, a non-profit organisation founded in 2013 and sponsored by firms including Mozilla, Cisco and Google Chrome. Obtaining certificates from Let’s Encrypt is free, and they are trusted by all major web browsers.

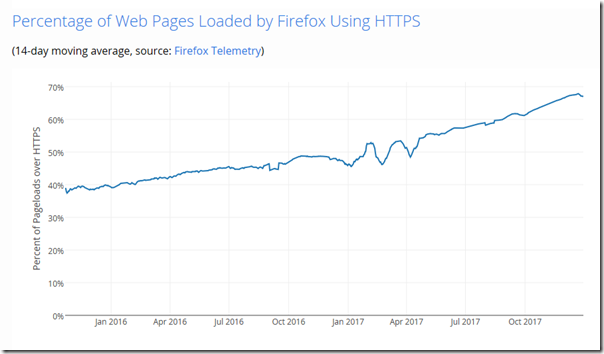

Last month Let’s Encrypt announced coming support for wildcard certificates as well as giving some stats: 46 million active certificates, and plans to double that in 2018. The post also notes that the latest figures from Firefox telemetry indicate that over 65% of the web is now served using HTTPS.

Source: https://letsencrypt.org/stats/

Let’s Encrypt only started issuing certificates in January 2016 so its growth is spectacular.

The reason is simple. Let’s Encrypt is saving the IT industry a huge amount in both money and time. Money, because its certificates are free. Time, because it is all about automation, and once you have the right automated process in place, renewal is automatic.

I have heard it said that Let’s Encrypt certificates are not proper certificates. This is not the case; they are just as trustworthy as those from the other SSL providers, with the caveat that everything is automated. Some types of certificate, such as those for code-signing, have additional verification performed by a human to ensure that they really are being requested by the organisation claimed. No such thing happens with the majority of SSL certificates, for which the process is entirely automated by all the providers and typically requires that the requester can receive email at the domain for which the certificate is issued. Let’s Encrypt uses other techniques, such as proof that you control the DNS for the domain, or are able to write a file to its website. Certificates that require human intervention will likely never be free.

A Let’s Encrypt certificate is only valid for three months, whereas those from commercial providers last at least a year. Despite appearances, this is not a disadvantage. If you automate the process, it is not inconvenient, and a certificate with a shorter life is more secure as it has less time to be compromised.

The ascendance of Let’s Encrypt is probably regretted both by the commercial certificate providers and by IT companies who make a bit of money from selling and administering certificates.

Let’s Encrypt certificates are issued in plain-text PEM (Privacy Enhanced Mail) format. Does that mean you cannot use them in Windows, which typically uses .cer or .pfx certificates? No, because it is easy to convert between formats. For example, you can use the openssl utility. Here is what I use on Linux to get a .pfx:

openssl pkcs12 -inkey privkey.pem -in fullchain.pem -export -out yourcert.pfx

If you have a website hosted for you by a third-party, can you use Let’s Encrypt? Maybe, but only if the hosting company offers this as a service. They may not be in a hurry to do so, since there is a bit of profit in selling SSL certificates, but on the other hand, a far-sighted ISP might win some business by offering free SSL as part of the service.

Implications of Let’s Encrypt

Let’s Encrypt removes the cost barrier for securing a web site, subject to the caveats mentioned above. At the same time, Google is gradually stepping up warnings in the Chrome browser when you visit unencrypted sites:

Eventually, we plan to show the “Not secure” warning for all HTTP pages, even outside Incognito mode.

Google search is also apparently weighted in favour of encrypted sites, so anyone who cares about their web presence or traffic is or will be using SSL.

Is this a good thing? Given the trivia (or worse) that constitutes most of the web, why bother encrypting it, which is slower and takes more processing power (bad for the planet)? Note also that encrypting the traffic does nothing to protect you from malware, nor does it insulate web developers from security bugs such as SQL injection attacks – which is why I prefer to call SSL sites encrypted rather than secure.

The big benefit though is that it makes it much harder to snoop on web traffic. This is good for privacy, especially if you are browsing the web over public Wi-Fi in cafes, hotels or airports. It would be a mistake though to imagine that if you are browsing the public web using HTTPS that you are really private: the sites you visit are still getting your data, including Facebook, Google and various other advertisers who track your browsing.

In the end it is worth it, if only to counter the number of times passwords are sent over the internet in plain text. Unfortunately people remain willing to send passwords by insecure email so there remains work to do.