I have just replaced my PC – well, if you count new motherboard, new CPU, new hard drive, new RAM as replacement, though it sits in the same case – and faced again the question of what to do with my Windows setup, complete with hundreds of applications.

A few years back, there was no question. You took every opportunity to do a clean install, because without it Windows gradually became unusable, as gloriously recounted by Verity Stob.

Stob’s analysis is not completely wrong today, but the matter has greatly improved. The Windows 7 64-bit installation that I use today was installed in August 2009 (run systeminfo if you want to check yours), and that was an in-place upgrade from Windows Vista 64-bit, as recorded here. That Vista install was done in January 2008, so I have preserved applications and settings for coming up to four years and two motherboard changes.

The trade-off is that in return for putting up with some cruft you get a big win in convenience. There is no need to dig out install media, downloads and licence codes, and migration to a new system is quicker.

So why complain? Well, although it can usually be done, moving Windows from one machine to another is not supported by Microsoft, unless the hardware is identical:

Microsoft does not support restoring a system state backup from one computer to a second computer of a different make, model, or hardware configuration. Microsoft will only provide commercially reasonable efforts to support this process. Even if the source and destination computers seem to be identical makes and models, there may be driver, hardware, or firmware differences between the source and destination computers.

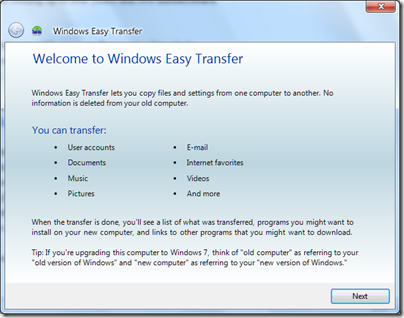

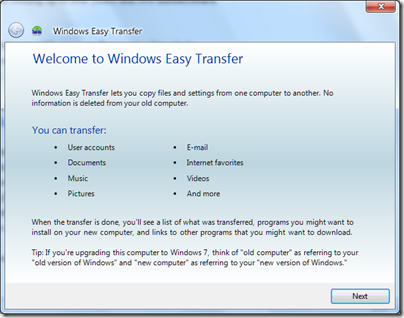

What this means is that users who get a new computer are directed instead towards the Windows Easy Transfer application:

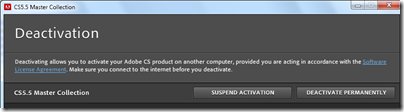

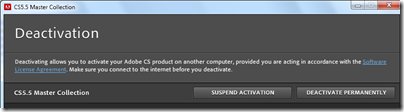

This is a handy tool, but it does not transfer applications. This last point can be particularly tiresome if you use software that requires activation on each machine on which it is installed, not least Microsoft’s own Windows and Office. Adobe’s Creative Suite, for example, allows installation on up to two machines, after which it will no longer install unless you specifically deactivate it:

If you trash your old PC, or it breaks, without deactivating first, then you have to call support and plead your case.

Apple’s Migration Assistant, by contrast, does move applications, making a better user experience.

If you can easily move applications, settings and data, of course, there is no need to move the entire operating system, since you have all that matters.

Why does Microsoft make this so hard? Two reasons I can think of.

One is that there are technical challenges in moving Windows to new hardware; though having said that, I suspect that Microsoft could easily have created a migration wizard that includes applications if it wished to do so.

The second, and more important, is licencing. Most consumer versions of Windows (and Office too) are OEM licences, which are not allowed to be transferred from the machine with which they are supplied. If Microsoft made it easier to move Windows or to migrate applications, less new software would be sold. Enterprises are expected to handle this in a different way, with centralised application management tools.

Virtualisation changes the game of course. The point of virtualisation is that you run the operating system on abstracted hardware that can easily be replicated on another machine. I really would like to run a virtual desktop, but I do not have a suitably high-powered server and there are niggles over fast graphics, USB devices, studio quality audio and so on. I expect all these to be solved and that a virtual desktop is in my future.

In the meantime, I have personally lost patience with the idea of reinstalling everything, and fortunately I do not use OEM Windows licences.

The wider question is interesting though. Although the desire of Microsoft and its partners to protect licence income is understandable, there are new models of application licencing that work better for users. In Google’s world you just sign on in your browser, and all your stuff is there. In Apple’s world, your iOS apps are licenced to you, not your device, and when you get a new device they all reappear. Even Microsoft’s Xbox works like this too, though that was not always the case.

This competition, in combination with virtualisation, means that Microsoft’s approach with Windows looks out of date as well as being unpleasant for users.

Windows 8 is on the horizon, and I would guess that the forthcoming Windows Store will be better in this respect, though note that at its Build conference in September Microsoft did not discuss the business aspects of the Store.