Acer kindly loaned me a Windows Mixed Reality headset to review, which I have been trying over the holiday period.

First, an aside. I had a couple of sessions with Windows Mixed Reality before doing this review. One was at IFA in Berlin at the end of August 2017, where the hardware and especially the software was described as late preview. The second was at the Future Decoded event in London, early November. On both occasions, I was guided through a session either by the hardware vendor or by Microsoft. Those sessions were useful for getting a hands-on experience; but an extended review at home has given me a different understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of the product. Readers beware: those rushed “reviews” based on hands-on sessions at vendor events are poor guides to what a product is really like.

A second observation: I wandered into a few computer game shops before Christmas and Windows Mixed Reality hardware was nowhere to be seen. That is partly because PC gaming has hardly any bricks and mortar presence now. Retailers focus on console gaming, where there is still some money to be made before all the software becomes download-only. PC game sales are now mainly Steam-powered, with a little bit of competition from other download stores including GOS and Microsoft’s Windows Store. That Steam and download dominance has many implications, one of which is invisibility on the High Street.

What about those people (and there must be some) who did unwrap a Windows Mixed Reality headset on Christmas morning? Well, unless they knew exactly what they were getting and enjoy being on the bleeding edge I’m guessing they will have been a little perplexed and disappointed. The problem is not the hardware, nor even Microsoft’s implementation of virtual reality. The problem is the lack of great games (or other virtual reality experiences).

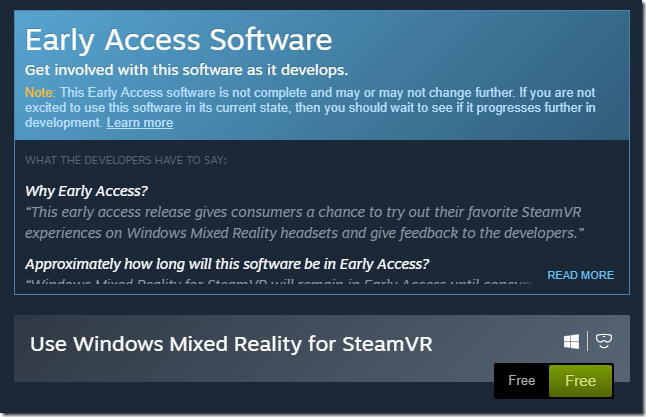

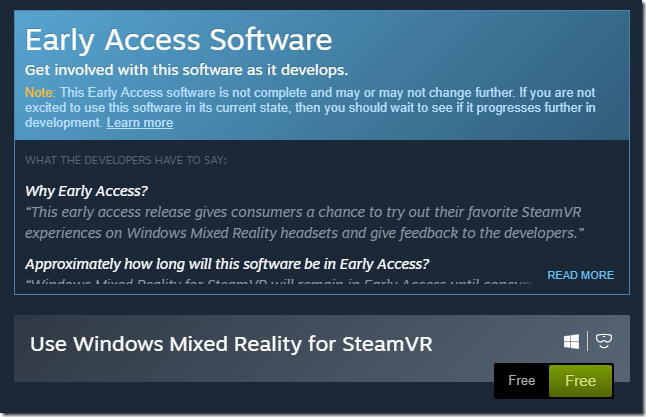

This may improve, provided Microsoft sustains enough momentum to make Windows Mixed Reality worth supporting. The key here is the relationship with Steam. Microsoft cheerfully told the press that Steam VR is supported. The reality is that Steam VR support comes via preview software which you get via Steam and which states that it “is not complete and may or may not change further.” It will probably all be fine eventually, but that is not reassuring for early adopters.

My experience so far is that native Windows MR apps (from the Microsoft Store) work more smoothly, but the best content is on Steam VR. The current Steam preview does work though with a few limitations (no haptic feedback) and other issues depending on how much effort the game developers have put into supporting Windows MR.

I tried Windows MR on a well-specified gaming PC: Core i7 with NVIDIA’s superb GTX 1080 GPU. Games in general run super smoothly on this hardware.

Getting started

A Windows Mixed Reality headset has a wired connection to a PC, broken out into an HDMI and a USB 3.0 connection. You need Windows 10 Fall Creators Update installed, and Setup should be a matter of plugging in your headset, whereupon the hardware is detected, and a setup wizard starts up, downloading additional software as required.

In my case it did not go well. Setup started OK but went into a spin, giving me a corrupt screen and never completing. The problem, it turned out, was that my GPU has only one HDMI port, which I was already using for the main display. I had the headset plugged into a DisplayPort socket via an adapter. I switched this around, so that the headset uses the real HDMI port, and the display uses the adapter. Everything then worked perfectly.

The controllers use Bluetooth. I was wary, because in my previous demos the controllers had been problematic, dropping their connection from time to time, but these work fine.

They are perhaps a bit bulky, thanks to their illuminated rings which are presumably a key part of the tracking system. They also chew batteries.

The Acer headsets are slightly cheaper than average, but I’ve enjoyed my time with this one. I wear glasses but the headset fits comfortably over them.

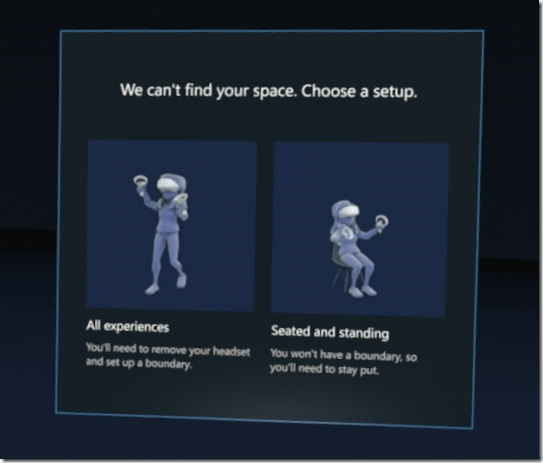

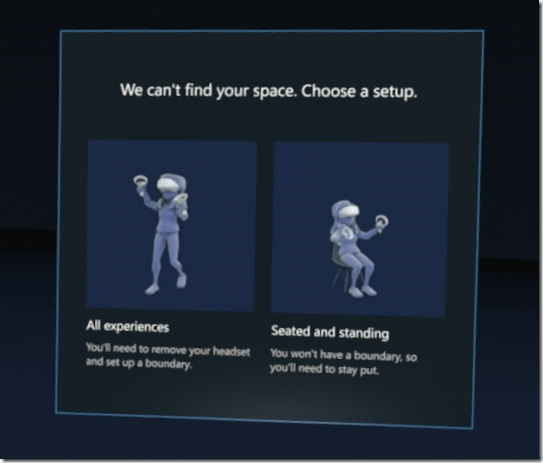

A big selling point of the Windows system is that no external tracking sensors are required. This is called inside-out tracking. It is a great feature and makes it easier just to plug in and go. That said, you have to choose between a stationary position, or free movement; and if you choose free movement, you have to set up a virtual boundary so that you do not walk into physical objects while immersed in a VR experience.

The boundary is an important feature but also illustrates an inherent issue with full VR immersion: you really are isolated from the real world. Motion sickness and disorientation can also be a problem, the reason being that the images your brain perceives do not match the physical movement your body feels.

Once set up, you are in Microsoft’s virtual house, which serves as a kind of customizable Start menu for your VR experiences.

The house is OK though it seems to me over-elaborate for its function, which is to launch games and apps.

I must state at this point that yes, a virtual reality experience is amazing and a new kind of computing. The ability to look all around is extraordinary when you first encounter it, and adds a level of realism which you cannot otherwise achieve. That said, there is some frustration when you discover that the virtual world is not really as extensive as it first appears, just as you get in an adventure game when you find that not all doors open and there are invisible barriers everywhere. I am pretty sure though that a must-have VR game will come along at some point and drive many new sales – though not necessarily for Windows Mixed Reality of course.

I looked for content in the Windows Store. It is slim pickings. There’s Minecraft, which is stunning in VR, until you realise that the controls do not work quite so well as they do in the conventional version. There is Space Pirate, an old-school arcade game which is a lot of fun. There is Arizona Sunshine, which is fine if you like shooting zombies.

I headed over to Steam. The way this works is that you install the Steam app, then launch Windows Mixed Reality, then launch a VR game from your Steam library. You can access the Windows Desktop from within the Windows MR world, though it is not much fun. Although the VR headset offers two 1440 x 1440 displays I found it impossible to keep everything in sharp focus all the time. This does not matter all that much in the context of a VR game or experience, but makes the desktop and desktop applications difficult to use.

I did find lots of goodies in the Steam VR store though. There is Google Earth VR, which is not marked as supporting Windows MR but works. There is also The Lab, which a Steam VR demo which does a great job of showing what the platform can do, with several mini-games and other experiences – including a fab archery game called Longbow where you defend your castle from approaching hordes. You can even fire flaming arrows.

Asteroids! VR, a short, wordless VR film which is nice to watch once. It’s free though!

Mainstream VR?

Irrespective of who provides the hardware, VR has some issues. Even with inside-out tracking, a Windows Mixed Reality setup is somewhat bulky and makes the wearer look silly. The kit will become lighter, as well as integrating audio. HTC’s Vive Pro, just announced at CES, offers built-in headphones and has a wireless option, using Intel’s WiGig technology.

Even so, there are inherent issues with a fully immersive environment. You are vulnerable in various ways. Having people around wearing earbuds and staring at a screen is bad enough, but VR takes anti-social to another level.

The added expense of creating the content is another issue, though the right tools can do an amazing job of simplifying and accelerating the process.

It is worth noting that VR has been around for a long time. Check out the history here. Virtual Reality arcade machines in 1991. Sega VR Glasses in 1993. Why has this stuff taken so long to take off, and remains in its early stages? It is partly about technology catching up to the point of real usability and affordability, but also an open question about how much VR we want and need.