David Sobeski, former Microsoft General Manager, has written about Trust, Users and The Developer Division. It is interesting to me since I recall all these changes: the evolution of the Microsoft C++ from Programmer’s Workbench (which few used) to Visual C++ and then Visual Studio; the original Visual Basic, the transition from VBX to OCX; DDE, OLE and OLE Automation and COM automation, the arrival of C# and .NET and the misery of Visual Basic developers who had to learn .NET; how DCOM (Distributed COM) was the future, especially in conjunction with Transaction Server, and then how it wasn’t, and XML web services were the future, with SOAP and WSDL, and then it wasn’t because REST is better; the transition from ASP to ASP.NET (totally different) to ASP.NET MVC (largely different); and of course the database APIs, the canonical case for Microsoft’s API mind-changing, as DAO gave way to ADO gave way to ADO.NET, not to mention various other SQL Server client libraries, and then there was LINQ and LINQ to SQL and Entity Framework and it is hard to keep up (speaking personally I have not yet really got to grips with Entity Framework).

There is much truth in what Sobeski says; yet his perspective is, I feel, overly negative. At least some of Microsoft’s changes were worthwhile. In particular, the transition to .NET and the introduction of C# was successful and it proved an strong and popular platform for business applications – more so than would have been the case if Microsoft had stuck with C++ and COM-based Visual Basic forever; and yes, the flight to Java would have been more pronounced if C# had not appeared.

Should Silverlight XAML have been “fully compatible” with WPF XAML as Sobeski suggests? I liked Silverlight; to me it was what client-side .NET should have been from the beginning, lightweight and web-friendly, and given its different aims it could never be fully compatible with WPF.

The ever-expanding Windows API is overly bloated and inconsistent for sure; but the code in Petzold’s Programming Windows mostly still works today, at least if you use the 32-bit edition (1998). In fact, Sobeski writes of the virtues of Win16 transitioning to Win32s and Win32 and Win64 in a mostly smooth fashion, without making it clear that this happened alongside the introduction of .NET and other changes.

Even Windows Forms, introduced with .NET in 2002, still works today. ADO.NET too has been resilient, and if you prefer not to use LINQ or Entity Framework then concepts you learned in 2002 will still work now, in Visual Studio 2013.

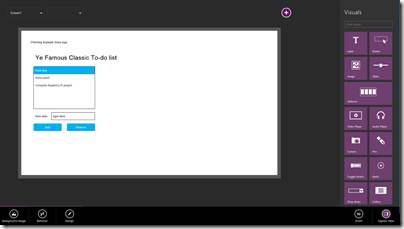

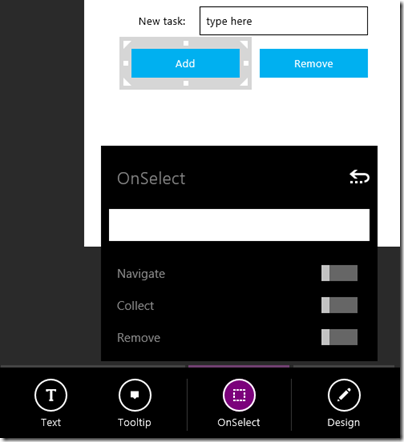

Why does this talk of developer trust then resonate so strongly? It is all to do with the Windows 8 story, not so much the move to Metro itself, but the way Microsoft communicated (or did not communicate) with developers and the abandonment of frameworks that were well liked. It was 2010 that was the darkest year for Microsoft platform developers. Up until Build in October, rumours swirled. Microsoft was abandoning .NET. Everything was going to be HTML or C++. Nobody would confirm or deny anything. Then at Build 2010 it became obvious that Silverlight was all-but dead, in terms of future development; the same Silverlight that a year earlier had been touted as the future both of the .NET client and the rich web platform, in Microsoft’s vision.

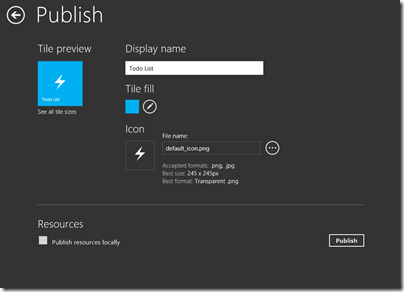

Developers had to wait a further year to discover what Microsoft meant by promoting HTML so strongly. It was all part of the strategy for the tablet-friendly Windows Runtime (WinRT), in which HTML, .NET and C++ are intended to be on an equal footing. Having said which, not all parts of the .NET Framework are supported, mainly because of the sandboxed WinRT environment.

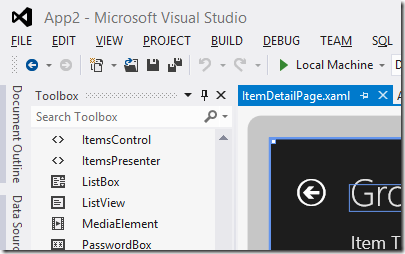

If you are a skilled Windows Forms developer, or a skilled Win32 developer, developing for WinRT is a hard transition, even though you can use a familiar language. If you are a skilled Silverlight or WPF developer, you have knowledge of XAML which is a substantial advantage, but there is still a great deal to learn and a great deal which no longer applies. Microsoft did this to shake off its legacy and avoid compromising the new platform; but the end result is not sufficiently wonderful to justify this rationale. In particular, there could have been more effort to incorporate Silverlight and the work done for Windows Phone (also a sandboxed and touch-based platform).

That said, I disagree with Sobeski’s conclusion:

At the end of the day, developers walked away from Microsoft not because they missed a platform paradigm shift. They left because they lost all trust. You wanted to go somewhere to have your code investments work and continue to work.

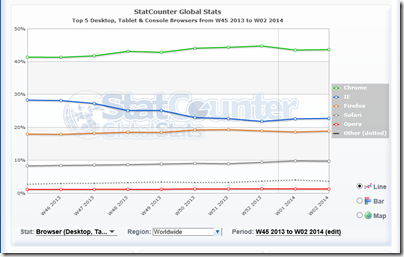

Developers go where the users are. The main reason developers have not rushed to support WinRT with new applications is that they can make more money elsewhere, coding for iOS and Android and desktop Windows. All Windows 8 machines other than those running Windows RT (a tiny minority) still run desktop applications, whereas no version of Windows below 8 runs WinRT apps, making it an easy decision.

Changing this state of affairs, if there is any hope of change, requires Microsoft to raise the profile of WinRT among users more than among developers, by selling more Windows tablets and by making the WinRT platform more compelling for users of those tablets. Winning developer support is a factor of course, but I do not take the view that lack of developer support is the chief reason for lacklustre Windows 8 adoption. There are many more obvious reasons, to do with the high demands a dual-personality operating system makes on users.

That said, the events of 2010 and 2011 hurt the Microsoft developer community deeply. The puzzle now is how the company can heal those wounds but without yet another strategy shift that will further undermine confidence in its platform.