What is happening with the Java language and runtime? Since Java passed into the hands of Oracle, following its acquisition of Sun, there has been a succession of bad news. To recap:

- The JavaOne conference in September 2010 was held in the shadow of Oracle OpenWorld making it a less significant event than in previous years.

- Oracle is suing Google, claiming that Java as used in the Android SDK breaches its copyright.

- IBM has abandoned the Apache open source Harmony project and is committing to the Oracle-supported Open JDK. Although IBM’s Sutor claims that this move will “help unify open source Java efforts”, it seems to have been done without consultation with Apache and is as much divisive as unifying.

- Apple is deprecating Java and ceasing to develop a Mac-specific JVM. This should be seen in context. Apple is averse to runtimes of any kind – note its war against Adobe Flash – and seems to look forward to a day when all or most applications delivered to Apple devices come via the Apple-curated and taxed app store. In mitigation, Apple is cooperating with the OpenJDK and OpenJDK for Mac OS X has been announced.

- Apache has written a strongly-worded blog post claiming that Oracle is “violating their contractual obligation as set forth under the rules of the JCP”, where JCP is the Java Community Process, a multi-vendor group responsible for the Java specification but in which Oracle/Sun has special powers of veto. Apache’s complaint is that Oracle stymies the progress of Harmony by refusing to supply the test kit for Java (TCK) under a free software license. Without the test kit, Harmony’s Java conformance cannot be officially verified.

- The JCP has been unhappy with Oracle’s handling of Java for some time. Many members disagree with the Google litigation and feel that Oracle has not communicated well with the JCP. JCP member Doug Lea stood down, claiming that “the JCP is no longer a credible specification and standards body”. Another member, Stephen Colebourne, has a series of blog posts in which he discusses the great war of Java and what he calls the “unravelling of the JCP”, and recently expressed his view that Oracle was trying to manipulate the recent JCP elections.

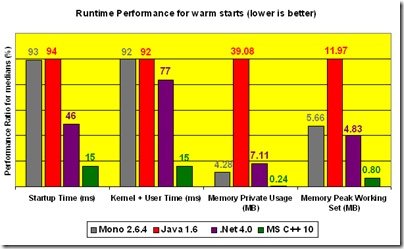

To set this bad news in context, Java was not really in a good way even before the acquisition. While Sun was more friendly towards open source and collaboration, the JCP has long been perceived as too slow to evolve Java, and unrepresentative of the wider Java community. Further, Java’s pre-eminence as a pervasive cross-platform runtime has been reduced. As a browser plug-in it has fallen behind Adobe Flash, the JavaFX initiative failed to win wide developer support, and on mobile it has also lost ground. Java’s advance as a language has been too slow to keep up with Microsoft’s C#.

There are a couple of ways to look at this.

One is to argue that bad news followed by more bad news means Java will become a kind of COBOL, widely used forever but not at the cutting edge of anything.

The other is to argue that since Java was already falling behind, radical change to the way it is managed may actually improve matters.

Mike Milinkovich at the Eclipse Foundation takes a pragmatic view in a recent post. He concedes that Oracle has no idea how to communicate with the Java community, and that the JCP is not vendor-neutral, but says that Java can nevertheless flourish:

I believe that many people are confusing the JCP’s vendor neutrality with its effectiveness as a specifications organization. The JCP has never and will never be a vendor-neutral organization (a la Apache and Eclipse), and anyone who thought it so was fooling themselves. But it has been effective, and I believe that it will be effective again.

It seems to me Java will be managed differently after it emerges from its crisis, and that on the scale between “open” and “proprietary” it will have moved towards proprietary but not in a way that destroys the basic Java proposition of a free development kit and runtime. It is also possible, even likely, that Java language and technology will advance more rapidly than before.

For developers wondering what will happen to Java at a technical level, the best guide currently is still the JDK Roadmap, published in September. Some of its key points:

- The open source Open JDK is the basis for the Oracle JDK.

- The Oracle JDK and Java Runtime Environment (JRE) will continue to be available as free downloads, with no changes to the existing licensing models.

- New features proposed for JDK 7 include better support for dynamic languages and concurrent programming. JDK 8 will get Lambda expression.

While I cannot predict the outcome of Oracle vs Google or even Apache vs Oracle, my guess is that there will be a settlement and that Android’s momentum will not be disrupted.

That said, there is little evidence that Oracle has the vision that Sun once had, to make Java truly pervasive and a defence against lock-in to proprietary operating systems. Microsoft seems to have lost that vision for .NET and Silverlight as well – though the Mono folk have it. Adobe still has it for Flash, though like Oracle it seems if anything to be retreating from open source.

There is therefore some sense in which the problems facing Java (and Silverlight) are good for .NET, for Mono and for Adobe. Nevertheless, 2010 has been a bad year for write once – run anywhere.

Update: Oracle has posted a statement saying:

The recently released statement by the ASF Board with regard to their participation in the JCP calling for EC members to vote against SE7 is a call for continued delay and stagnation of the past several years. We would encourage Apache to reconsider their position and work together with Oracle and the community at large to collectively move Java forward. Oracle provides TCK licenses under fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory terms consistent with its obligations under the JSPA. Oracle believes that with EC approval to initiate the SE7 and SE8 JSRs, the Java community can get on with the important work of driving forward Java SE and other standards in open, transparent, consensus-driven expert groups. This is the priority. Now is the time for positive action. Now is the time to move Java forward.

to which Apache replies succinctly:

The ball is in your court. Honor the agreement.