Earlier today I posted a story speculating about the future direction of Microsoft’s development platform, which has proved controversial and to some extent has been misunderstood. Although it is speculative, the issues are important since developers want to target platforms with a strong future. Here’s another take on why Microsoft, whichever way it decides to go, faces some difficult choices.

First, let me be clear: I don’t see Microsoft abandoning Windows Presentation Foundation let alone Silverlight. Microsoft has an good track record when it comes to continuing support for its technologies, better than competing platforms. Visual Basic 6 applications mostly still run today on Windows 7, perhaps with a few issues caused by User Account Control for which there are workarounds. Whatever you target, there is an excellent chance Microsoft will continue to support it long into the future. The main exception I can think of is Windows Mobile, which is incompatible with the new Windows Phone 7 series, but given the challenges Microsoft faces in mobile you can understand the decision.

Nor is there any chance of Microsoft reviving old frameworks. There will not be a return to Windows Forms. WPF is a better GUI framework in every way, other than performance on older systems – though note that Windows Forms applications still run fine today, and I imagine will run fine on Windows 8 and probably 9 as well.

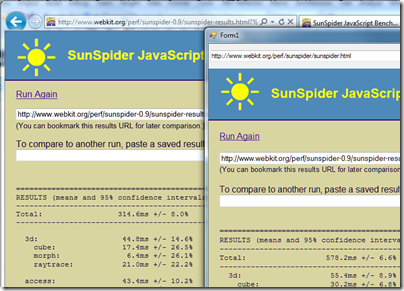

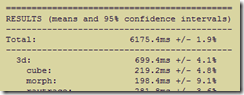

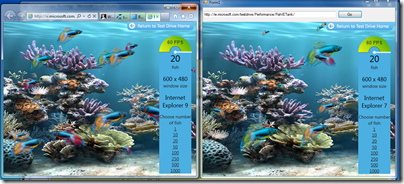

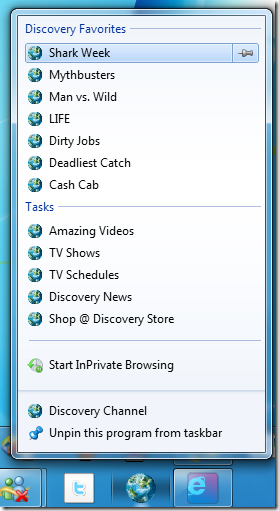

The real question is not about support, but future investment. Microsoft has finite resources. It is in overdrive right now on Internet Explorer, on Silverlight, on Windows Phone 7, and on Azure, for example. There will be other products and technologies that receive less attention, because someone has decided they are not strategic.

It also seems to me that Microsoft’s server and cloud story is less conflicted. From the developer’s perspective it is thoroughly .NET based, and you can be confident that technologies like C#, IIS, ASP.NET, SQL Server, Exchange and SharePoint will be around for the foreseeable future.

With that out of the way, a few further comments.

Windows Presentation Foundation

The history of WPF goes back to the early days of Windows Vista, then called Longhorn. WPF was one of the the “three pillars”, Avalon, where the others were Indigo (WCF) and WinFS. Avalon was the future of the Windows GUI API, based on .NET code and XAML layout.

If Longhorn has proceeded as planned, WPF would be the loose equivalent of Cocoa on Apple’s OS X, the standard way to code Windows GUI applications. Unfortunately, in 2004, Microsoft discovered that Longhorn was heading for disaster. The project was reset, delaying release and resulting in Vista being both late and rushed. The reset project included Avalon as a supported framework, but made it incidental to the workings of Windows itself. The Windows team, in other words, lost faith in Avalon and reverted to native code with a dash of DirectX.

Windows 7 is more of the same. WPF is there but it is not at the heart of the OS. Developers are encouraged to use it for their own apps, but the Windows team is focused on native code.

When Visual Studio 2010 was released, with a shell built in WPF, Microsoft made some noise about how it showed its commitment to the framework. It was also noted that the Visual Studio team had worked with the WPF team to fix some issues. However, there is little sign of WPF changing its role as a layer in Windows primarily to support custom applications, rather than being used for the shell of Windows itself.

The question now: how much should Microsoft invest in future WPF development? It is not essential for Windows itself. Nor it is compelling for developers wanting to take advantage of the cloud model and support diverse clients. Frankly it does not look strategic unless it becomes the Windows shell API; and you could understand Microsoft having a “once bitten twice shy” attitude to that possibility.

I find it plausible that Microsoft would throttle back on WPF development.

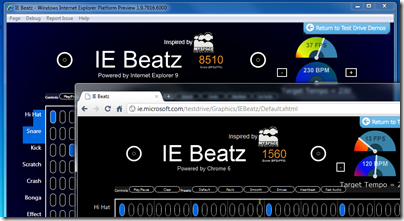

Silverlight

Silverlight by contrast is strategic. Silverlight is a framework that runs in the browser, out of browser, and on Windows Phone 7. It is lightweight and cloud-oriented, and it runs .NET code, ticking lots of boxes for developers moving on from Windows desktop applications. It is also designer-friendly, with rich graphics and multimedia support. There are still a few gaps – printing is crude, for example – but it makes more sense for Microsoft to invest in Silverlight than WPF. It is significant that the new LightSwitch tool for rapid development of database apps targets Silverlight, not WPF, and not ASP.NET (except on the server). Silverlight is also the application platform for Windows Phone 7.

Then again, Silverlight is WPF. It was originally WPF/Everywhere, and uses the same XAML language for layout.

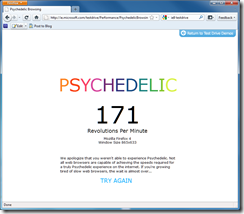

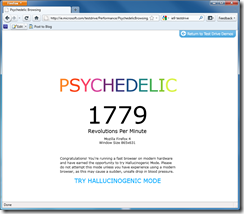

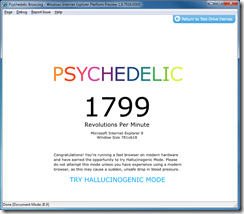

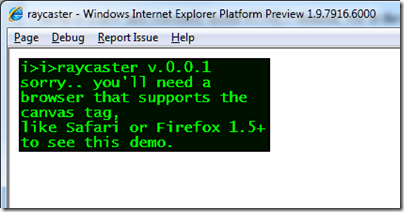

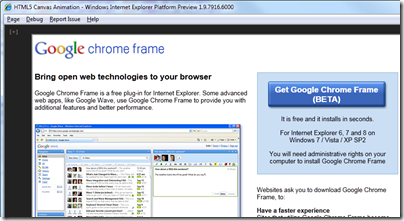

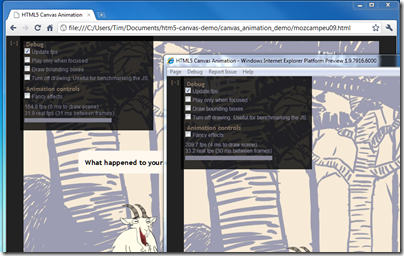

I will be surprised if Microsoft back-pedals on Silverlight. Nevertheless, I can also understand this being a matter of debate. Despite Microsoft’s efforts to distinguish them, there is considerable overlap between what Silverlight does, and what HTML 5 in IE9 does, especially when in the browser. There is also the Apple problem: HTML applications will run on iPhone and iPad, but Silverlight will not. What if Microsoft focused on the new IE engine instead of Silverlight, supporting it properly in Visual Studio, and providing ways for developers to create out-of-browser apps that run with full trust and have access to local system APIs? This would be along the same lines as the Palm WebOS and Google’s Chrome OS.

Put another way, does it make sense for Microsoft to invest equally in HTML 5 and Silverlight, when possibly IE 9 could be the basis of a unifying technology, a subset of which would work on any modern browser on any client?

It seems to me that Microsoft will have to invest in tooling for HTML 5 clients in some forthcoming edition of Visual Studio, and that this will be a selling point for its cloud platform, while possibly undermining the role of Silverlight.

There is also a continuing case for Silverlight, both because of the inherent advantages of a plug-in – consistency of client platform as well as features that HTML 5 lacks – and because it supports .NET. The .NET languages (Mono aside) tie developers to Visual Studio and to Microsoft’s platform. Visual Studio combined with .NET is a formidable tool for both client and server and a key advantage for the platform.

Watch this space.