Adobe has announced Experience Manager Apps for Marketers and Developers. This comes in two flavours: Experience Manager Apps is for marketers, and PhoneGap Enterprise is for developers. The announcements are unfortunately sketchy when it comes to details, though Andre Charland’s post has a little more:

-

Better collaboration – With our new PhoneGap Enterprise app, developer team members and business colleagues can view the latest version of apps in production, development and staging

-

App editing capabilities – Non-developer colleagues can edit and improve the app experience using a simple drag-and-drop interface from the new Adobe Experience Manager apps; this way developers can focus on building new features, not on making updates.

-

Analytics & optimization – Teams can immediately start measuring app performance with Adobe Analytics; we’re also planning to incorporate functionality so teams can start A/B testing their way to higher app engagement and monetization using Adobe Target.

-

Push notifications – Engage your customers on-the-go with push notifications from Adobe Campaign

-

Support and training – PhoneGap Enterprise comes with SLA and support so customers can be rest assured that Adobe PhoneGap has their back.

Head over to the PhoneGap Enterprise site and you get nothing more than a “Get in touch” button.

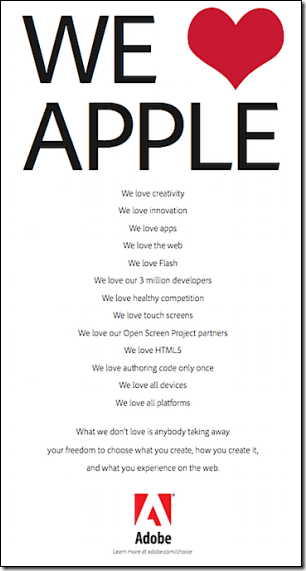

Announcement-ware then. Still, enough to rile Flash and AIR (Adobe Integrated Runtime) developers who feel that Adobe is abandoning a better technology for app development. Despite the absence of the Flash runtime on Apple iOS, you can still build mobile apps by compiling the code with a native wrapper.

Adobe… this whole thread should make you realize what an awesome platform and die hard fans you have in AIR. Even after all that crap you pulled with screwing over Flex developers, mitigating Flash to just games, retreating it from the web, killing AS4 and god knows what else you’ve done to try to kill the community’s spirit. WE STILL WANT AIR!

says one frustrated developer.

Gary Paluk has also posted on the subject:

I have invested 13 years of my own development career in Adobe products and evangelized the technology over that time. Your users can see that there is a perfectly good technology that does more than the new HTML5 offerings and they are evidently frustrated that you are not supporting developers that do not understand why they are being forced to retrain to use inferior technologies.

Has Adobe in fact abandoned Flash and AIR? Not quite; but as this detailed roadmap shows, plans for a next-generation Flash player have been abandoned and Adobe is now focused on “web-based virtual machines,” meaning I guess JavaScript and other browser technologies:

Adobe will focus its future Flash Player development on top of the existing Flash Player architecture and virtual machine, and not on a completely new virtual machine and architecture (Flash Player "Next") as was previously planned. At the same time, Adobe plans to continue its next-generation virtual machine and language work as part of the larger web community doing such work on web-based virtual machines.

From my perspective, Adobe seemed to mostly lose interest in the developer community after its November 2011 shift to digital marketing, other than in an “apps for marketing” context. Its design tools on the other hand go from strength to strength, and the transition to subscription in the form of Creative Cloud has been brilliantly executed.