I imagine there must be urgent meetings taking place at Adobe following Apple’s prohibition of Flash content or applications on its iPhone and iPad devices, and last week’s open letter from Apple CEO Steve Jobs which leaves little hope of a change in policy.

The problem is that until now Adobe has put the Flash runtime at the heart of its strategy. The Flash Platform is a suite of tools and technologies including middleware (LiveCycle Data Services), web and desktop runtimes (Flash and AIR), design and developer tools (Creative Suite and Flash Builder). The company has worked to integrate Flash and PDF, using embedded Flash content for multimedia and to blur the boundaries between documents and applications.

If you look at Creative Suite 5, the latest release of Adobe’s flagship tools and from which it derives most of its revenue, there is scarcely a product within it which Flash does not touch.

Adobe’s hosted document and collaboration platform, Acrobat.com, uses Flash for online document viewing and editing, for web conferencing, for online presentations.

Adobe’s abandoned Flash to iPhone compiler was not only something for third-party developers, but also for Adobe itself, and the company has already been using it to enable access from iPhone to some of its Flash-based online services. For example, Adobe Acrobat Connect Pro Mobile for iPhone, which lets you attend Acrobat Connect Pro meetings:

This application was developed using the Flash platform and the Packager for iPhone to publish it as a native iPhone application. We will also be able to use the same code to deliver this application on other mobile devices when AIR for mobile devices becomes available later this year.

Of course Adobe is not solely a Flash company. It’s also a PDF company, and while there is no Adobe Reader for iPhone, it is at least possible to view PDFs on Apple’s devices. Adobe is an HTML company too, and products like Dreamweaver and Fireworks are geared towards HTML content.

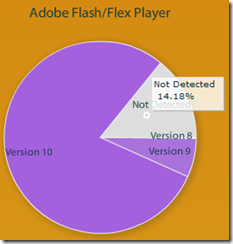

Still, Apple has created a big problem for Adobe. The appeal of the Flash Platform starts with the ubiquity of the runtime.

Let’s assume that Apple trundles on, grabbing an increasing share of the Smartphone market and encroaching into what we now think of as the laptop/netbook market with iPad and possibly other appliance-type computing devices. What can Adobe do? Here are a couple of top-level choices that occur to me:

1. Resign itself to being an anything-but-Apple company. There is life beyond iPhone and iPad; and Adobe is making good progress towards establishing Flash elsewhere, from Android mobiles to set-top boxes to games consoles. Unfortunately the Apple-owning community is a wealthy and influential one; the impact of losing that part of the market is greater than its market share implies. Nevertheless, this seems to be Adobe’s immediate reaction to the Jobs bombshell. It is rumoured to be giving Android phones to its employees, for example, and there are signs of an Adobe-Google alliance forming against Apple – note that Google is building Flash by default into its Chrome browser.

2. Pull back on Flash. For example, redesign Buzzword, its Flash-based online document editor, in HTML and JavaScript. Tune its PR message to emphasise how useful its tools are in an non-Flash context, rather than presuming its runtime will be everywhere. I think Adobe will have to do this to some extent.

A mitigating factor is that while Adobe has (until now) done a great job of deploying the Flash runtime, it has done less well at monetising it. If you look at its latest financials, you’ll see that Flash Platform (including AIR) accounted for only 6% of its revenue, compared to 50% for design tools including Creative Suite and Photoshop, 28% for business use of Acrobat, and 10% for the recently acquired Omniture web analytics. Although some of its design market is Flash-dependent, there is plenty more that is not.