I have been trying a Marley Stir it Up Wireless turntable over the last couple of weeks.

This is the wireless version of an older model, also called Stir it up. The name references a Bob Marley song, and yes there is a family connection. Marley manufactures a range of relatively inexpensive audio products with a distinctive emphasis on natural and recycled materials.

The turntable is no exception, and has an attractive bamboo plinth and a fabric cover in place of the usual Perspex (or similar) lid. The fabric cover is actually a bit annoying, since you cannot use it when a record is playing (it would flop all over it).

I am familiar with turntable setup, and otherwise would have found the setup instructions confusing. The belt is a suppled already fitted to the platter. You have to poke it round the drive pulley through a hole in the platter. That is not too hard, but there also conflicting and unclear instructions about how to set the tracking weight and bias correction. What you should do is to ignore the printed instructions and check out the video here. This explains that you fit the counterweight to the arm, adjust it until the cartridge floats just above the platter, then twist the weight gauge to zero, then twist the counterweight to 2.5g, the correct tracking force for the supplied Audio Technical 3600L cartridge. Then set the anti-skate to the same value as the tracking weight.

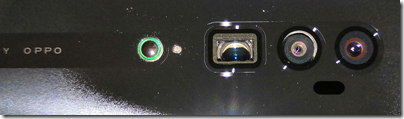

Connections on this turntable are flexible. You can switch the phono pre-amp on or off; if ON you do not need a phono input on your amplifier, just line in. Alternatively you can plug in headphones, or connect Bluetooth speakers, using the volume control at front right.

There is also a USB port at the back of the unit. You can connect this to a PC or Mac to convert records to audio files.

Playing record is a matter of placing the record on the platter, setting the speed as required, unclipping the arm, pulling the arm lowering lever FORWARD to lift it, moving the arm over the record (which starts the platter rotating), then pushing the lever BACK to lower it (I found the lever worked the opposite way to what I expected).

All worked well though, and I was soon playing records. First impressions were good. I found the sound quality decent enough to be enjoyable and put on a few favourites. My question had been: can a cheapish turntable deliver good enough sound to make playing records fun? The answer, I felt, was yes.

This was despite some obvious weaknesses in the turntable. The arm does not move as freely as a top quality arm, and the fact that it operates a switch is sub-optimal; it is better to have a separate switch to turn the platter rotation on and off. I also noticed mechanical noise from the turntable, not enough to be spoil the music, but a bad sign. The cartridge is from a great manufacturer, but is about the cheapest in the range. Finally, the platter is lightweight, which is bad for speed stability.

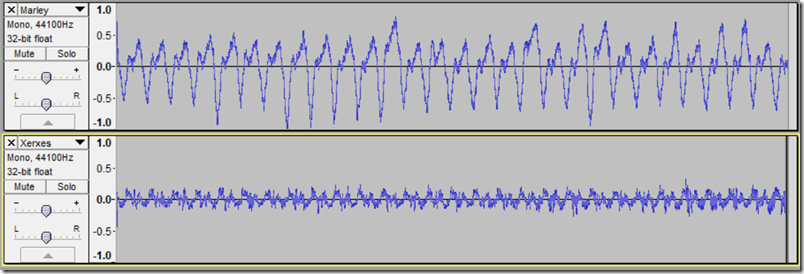

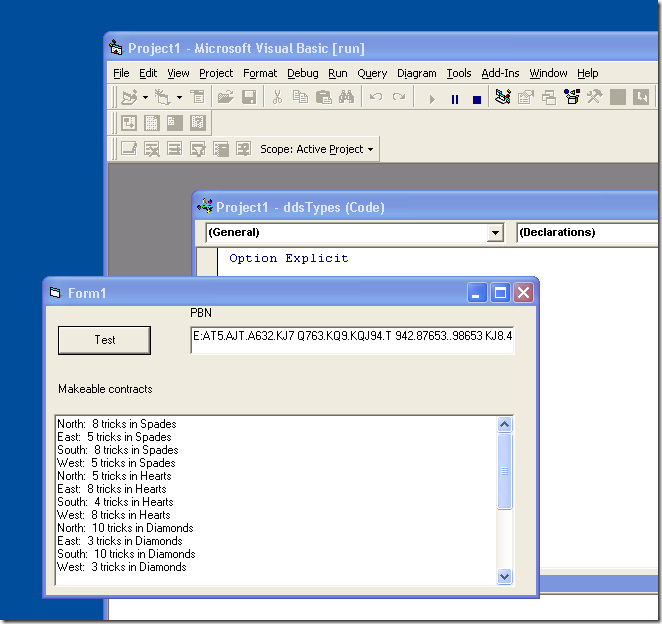

This last point is important. I noticed that on some material the pitch was not as stable as it should be. Marley quote “less than 0.3%” for wow and flutter, which is rather high. I decided to do some measurement. I recorded a 3.15kHz tone into a digital recorded and opened the file in Audacity. Then I used the Wow and Flutter visualizer plugin from here. I repeated the test with my normal (old but much more expensive) turntable, a Roksan Xerxes, to get a comparison. In the following analysis, the +/- 1.0 represents 1% divergence from the average frequency. A perfect result would be a straight line. The Marley is the top chart, the Xerxes below.

Essentially this shows a cyclic speed variation of up to about 1.8% peak to peak for the Marley, compared to around 0.4% for the Xerxes. Note that when converted to weighted RMS (root mean square) this is probably within spec for the Marley; but it is also obvious that the Marley is pretty bad. Does it matter? Well, it is certainly audible. Whether it bothers you depends partly on the kind of music you play, and partly on your sensitivity to this kind of distortion. I noticed it easily on Kind of Blue by Miles Davis, not so much on rock music.

The Marley is £229 full retail. Can you do better for the same price? That is hard to answer since the Marley does pack in a lot of flexibility. All you need to add is a Bluetooth speaker, or headphones, and you can listen to music. If you compare the Rega Planar 1, which is £229, you do get a turntable more obviously designed for best quality at the price, but it is more of a bare-bones design, lacking the phono pre-amp, headphone socket and wireless capabilities. And even the Rega Planar 1 does not have a great spec for wow and flutter; I cannot find a published spec but I believe it is around 0.2% – there is a discussion here.

I still feel the Marley is a good buy if you want to have some fun playing records, but getting the best quality out of records has never been cheap and this is true today as it was in the LP’s heyday back in the 60s and 70s.

I cannot fault the AT cartridge which gives a clean and lively sound. The headphone output is not very loud, but fine for some casual listening.

Is there any point, when streaming is so easy? All I can say is that playing records is good fun and at its best offers an organic, three-dimensional sound quality that you do not often hear from a digital source. Quite often records are less compressed than digital versions of the same music, which is also a reason why they can sound better. In terms of signal to noise, wow and flutter, distortion etc, digital is of course superior.