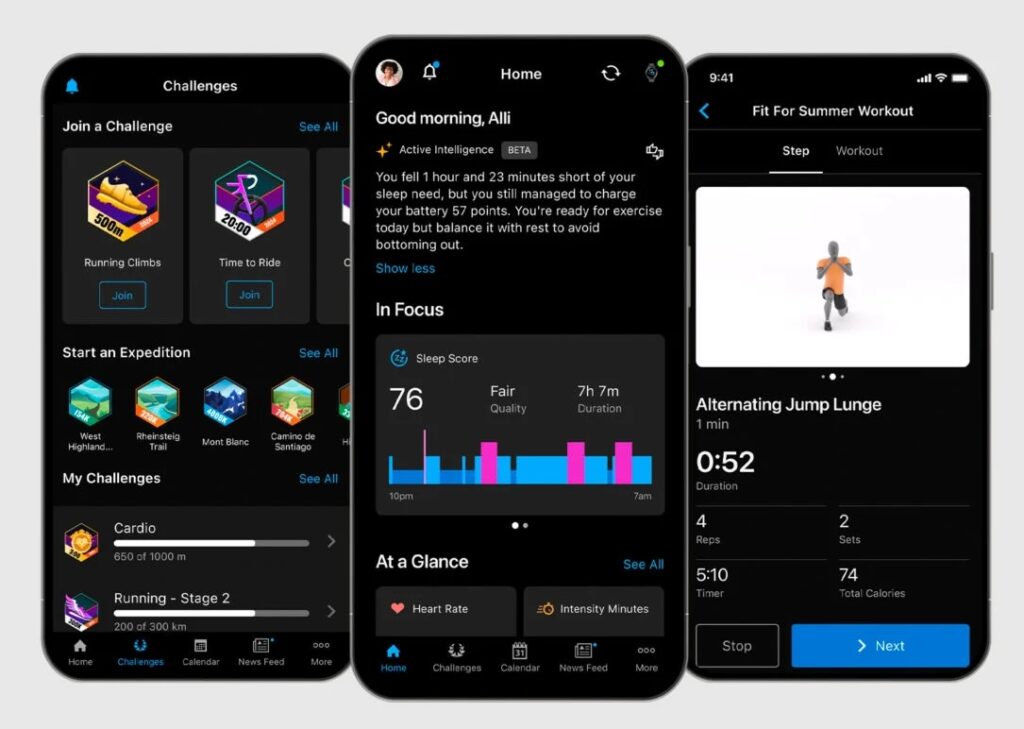

Garmin, makers of sports watches which gather health and performance data on your activities, has announced Connect+, a subscription offering with “premium features and more personalised insights.”

Garmin Connect is the cloud-based application that stores and manages user data, such as the route, pace and heart rate, on runs, cycle rides and other workouts, as well as providing a user interface which lets you browse and analyse this data. The mobile app is a slightly cut-down version of the web app. Until now, this service has been free to all customers of Garmin wearable devices.

The company stated that Garmin Connect+ is a “premium plan that provides new features and even more personalized insights … with Active Intelligence insights powered by AI.” It also promised customers that “all existing features and data in Garmin Connect will remain free.” The subscription costs $6.99 per month or $69.99 per year. UK price is £6.99 per month or £69.99 per year which is a bit more expensive.

The reaction from Garmin’s considerable community has been largely negative. The Garmin forum on Reddit which has over 266,000 members is full of complaints, not only because the subscription is considered poor value but also from fear that despite the company’s reassurance the free Garmin Connect service will get worse, perhaps becoming ad-laden or just less useful as all the investment in improvements is switched to the premium version.

On the official Garmin forums an initial thread filled quickly with complaints and was locked; and a new thread is going in the same direction. For example:

“I paid £800 for my Descent Mk2s with the understanding that there WAS NO SUBSCRIPTION and the high cost of my device subsidised the Connect platform. The mere existence of the paid platform is a clear sign that all/most new features will go to the paid version and the base platform will get nothing. You’ve broken all trust here Garmin, I was waiting for the next Descent to upgrade but I will look elsewhere now.”

A few observations:

- Companies love subscriptions because they give a near-guaranteed and continuous revenue stream.

- The subscription model combined with hardware can have a strange and generally negative impact on the customer, with the obvious example being printers where selling ink has proved more profitable than selling printers, to the point where some printers are designed with deliberately small-capacity cartridges and sold cheaply; the sale of the hardware can also be seen as the purchase of an income stream from ink sales.

- A Garmin wearable is a cloud-connected device and is inconvenient to use without the cloud service behind it. For example, I am a runner with a Garmin watch; when I add a training schedule I do so in the Connect web application, which then syncs with the watch so that while I am training the watch tells me how I am doing, too fast, too slow, heart rate higher than planned, and so on. That service costs money to provide so it may seem reasonable for Garmin to charge for it.

- The counter-argument is that customers have purchased Garmin devices, which are more expensive than similar hardware from other vendors, in part on the basis that they include a high quality cloud service for no additional cost. Such customers now feel let down.

- We need to think about how the subscription changes the incentives for the company. The business model until now has included the idea that more expensive watches light up different data-driven features. Sometimes these features depend on hardware sensors that only exist in the premium devices, but sometimes it is just that the device operating system is deliberately crippled on the cheaper models. Adding the subscription element to the mix gives Garmin an incentive to improve the premium cloud service to add features, rather than improving the hardware and on-device software.

- It follows from this that owners of the cheapest Garmin watches will get the least value from the subscription, because their hardware does not support as many features. Will the company now aim to sell watches with hitherto premium features more cheaply, to improve the value of the subscription? Or will it be more concerned to preserve the premium features of its more expensive devices to justify their higher price?

- It was predictable that breaking this news would be difficult: it is informing customers that a service that was previously completely free will now have a freemium model. The promise that existing free features would remain free has done little to reassure users, who assume either that this promise will not be kept, or that the free version will become gradually worse in comparison with the paid option. Could the company have handled this better? More engagement with users would perhaps help.

Finally, it seems to me that Connect+ will be a hard sell, for two reasons. First, Strava has already largely captured the social connection aspect of this type of service, and many Garmin users primarily use Strava as a result. Remarkably, even the free Strava is ad-free (other than for prompts to subscribe) and quite feature-rich. Few will want to subscribe both to Strava and Connect+, and Strava is likely to win this one.

Second, the AI aspect (which is expensive for the provider) has yet to prove its worth. From what I have seen, Strava’s Athlete Intelligence mostly provides banal feedback that offers no in-depth insight.

While one understands the reasons which are driving Garmin towards a subscription model, it has also given the company a tricky path to navigate.