There were two big ideas behind Surface RT and Windows RT, the 2012 Windows 8 project which left Microsoft (and some OEM partners) with a mountain of unsold hardware. One was to compete with iPads and Android tablets by making Windows a touch-friendly operating system. The second was that Windows had to move on from being vulnerable to being damaged or completely broken by applications. Traditional Windows applications have installers that run with full admin rights and there is nothing much to stop them installing files in the wrong places, setting themselves to start up automatically, or bloating the Registry (the central configuration database in Windows). “My PC is so slow” is a common complaint, and the cumulative effect of successive application installs is one of the key reasons. Vulnerability to malware is another problem, and one which anti-virus software can never solve completely.

Windows RT solved these problems by disallowing application installs other than via the Windows Store. At that time, Windows Store apps were also locked down, so that a malware infection was only possible if there were a bug in the operating system.

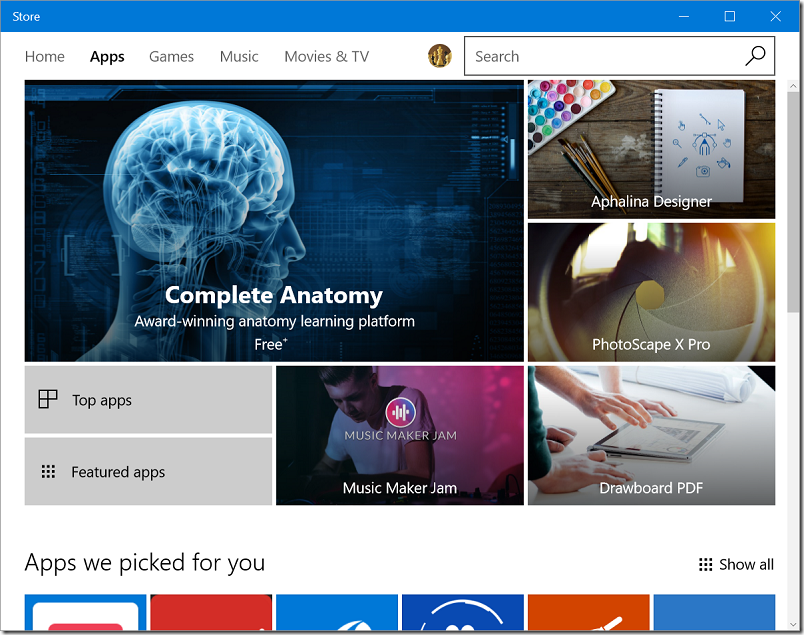

Why did Surface RT and Windows RT fail? The ARM-based hardware was rather slow, which was one of the issues, but a more serious flaw was the lack of compelling applications in the Store. Why was that? Complex reasons, but the chief one is that Windows RT was caught in a cycle of failure. Developers want to make money, and the Windows 8 Store was not sufficiently popular with users to give them a big market. At the same time, users who tried the Store found few applications worth their time, and therefore rarely used it.

The problem was compounded by the unpopularity of Windows 8, which was an unfamiliar environment for the existing Windows users who formed the primary market.

Nevertheless, the thinking behind Windows 8 and Windows RT was not completely off the mark. If only it could get over the hump of unpopularity and lack of apps, it could usher in a new era of Windows devices that were secure, touch-friendly, and resistant to performance decay.

It never did, and with Windows 10 Microsoft appeared to give up. The desktop was back, mouse and keyboard was again primary, and Store apps now ran in windows on the desktop. A special Tablet Mode attempted to make Windows 10 equally as touch-friendly as Windows 8, but did not succeed.

Windows still has those problems though, the ones which Windows RT was intended to solve. Could there be another approach which would fix those issues but in a manner more acceptable to users?

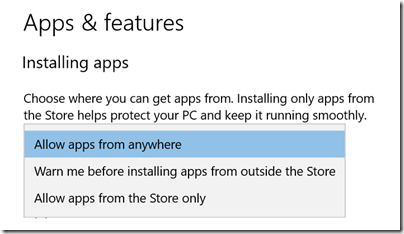

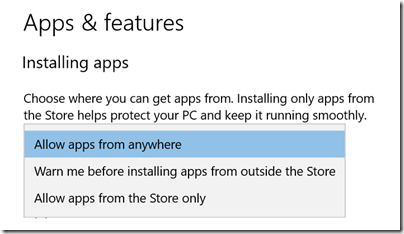

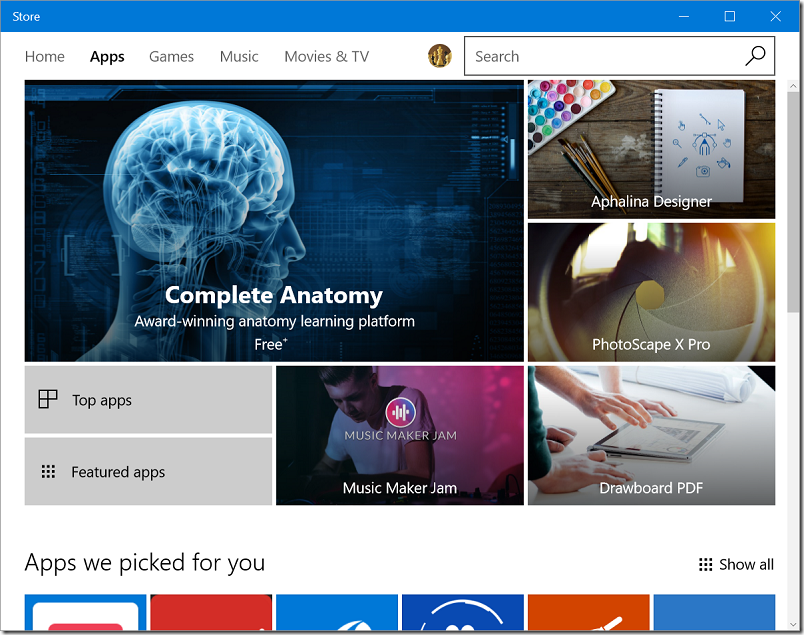

Windows S and the Surface Laptop, announced today in New York, is the outcome. It is still Windows 10, but Microsoft has flipped a switch that enforces all apps to be installed from the Windows Store. This switch is already in the latest version of Windows 10, the Creators Update, but off by default:

Microsoft has also taken steps to make the Store more attractive for developers. It is no longer necessary to develop apps on a new platform within Windows, as it was for the Windows 8 Store. Now you can simply take your existing desktop application and wrap it to enable Store download. This feature is called the Desktop Bridge, or Project Centennial. Applications so wrapped are not as secure as Windows 8 Store apps were; they can write to files anywhere that the user has permission. At the same time, Microsoft has taken steps to make Desktop Bridge apps better isolated than normal desktop applications. You can read the details of how this works here. It is arranged that applications install all files to a private location, instead of system locations, and that Windows hides this fact from the application code by using redirection. The same is true of the registry. This approach means that file version problems and registry bloat are much less likely. Such issues are still possible because the Desktop Bridge does not redirect file or registry calls outside the application package; these are allowed if the user has permission, for compatibility reasons. Nevertheless, it is a big advance on old-style Windows desktop application installs.

When the user removes a Desktop Bridge application, in most cases all its files and registry entries are cleanly removed.

An important additional protection is that applications submitted to the Store are vetted by Microsoft, so malicious or badly behaved instances should not get through.

Windows S will be installed by default both on Surface Laptop and on a new generation of low-end laptops aimed mainly at the education market.

The benefits of Windows S are real; but unfortunately Microsoft still has not solved the Store problem. Currently, your favourite Windows applications are not in the Store. Microsoft Office will be there, thanks to the Desktop Bridge, but many others are not.

Microsoft’s big bet is that thanks to Windows S and other initiatives, the Store will be sufficiently attractive to developers, and sufficiently easy to target, that it will soon offer a full range of applications including all your favourites.

Right now though, if you get a Windows S laptop, you will probably end up buying the upgrade to Windows 10 Pro, for $49.00 or equivalent. Then you can install any Windows desktop application. However, by doing so you make it unnecessary for developers to bother using Desktop Bridge to wrap their applications – so they might never do so.

Windows S has a few other limitations:

Microsoft Edge is the default web browser on Microsoft 10 S. You are able to download another browser that might be available from the Windows Store, but Microsoft Edge will remain the default if, for example, you open an .htm file. Additionally, the default search provider in Microsoft Edge and Internet Explorer cannot be changed.

In addition, it cannot join a local Windows domain (a problem for many businesses), though it can join Azure AD, the Office 365 directory.

Microsoft’s goal here is worthwhile: to move Windows into a new place in terms of security and resilience. Getting it there though will not be easy.