Microsoft has announced its most expensive acquisition yet, taking over LinkedIn for $26.2 billion. The transaction is expected to close later in 2016.

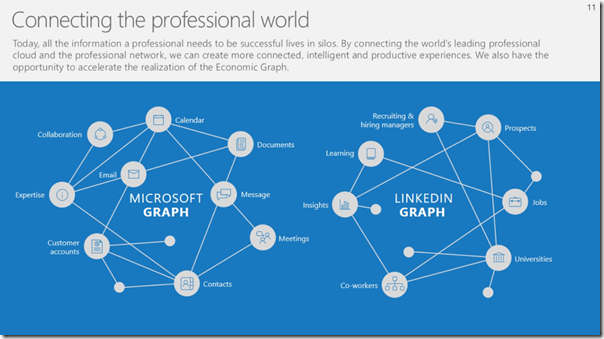

Why? It’s about combining data from Office 365 with LinkedIn’s data on who works where. According to Microsoft, it’s “the word’s first economic graph, a digital mapping of the global economy,” said Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella. “If you connect these two graphs, that’s where the magic starts to happen.”

LinkedIn is not just a social network with a business flavour, but also offers online training thanks to its April 2015 acquisition of Lynda.com.

“A professional’s profile will be unified,” says the presentation, “and the right data at the right time will surface in an app, whether Outlook, Skype, Office or elsewhere.”

There is obvious synergy with Dynamics CRM for customer relationship building and “social selling” – which, at its best, is the ability to be there at the right time with the right offer for your product or service, having nurtured a relationship over a long period.

There is even an offer to “empower developers in new ways with rich APIs and new training opportunities.”

Will it work?

Microsoft is not good at acquisitions. That is in part because of its own internal politics, leading to tragedies like the takeover of Danger in 2008, a strong company with a strategic product that was so mismanaged following the takeover that it lead to the Kin disaster. Then there was Nokia, a perfect fit for Steve Ballmer’s strategy of “win at all costs” with Windows Phone, and a perfect misfit for Nadella’s “cloud plus any device” approach, leading to the dismantling of the acquired assets and most of the employees with huge destruction of value.

What about Yammer, acquired for $1.2 billion in 2012, to “accelerate Yammer’s adoption alongside complementary offerings from Microsoft SharePoint, Office 365, Microsoft Dynamics and Skype?” It is near-invisible today. Or Skype, $8.5 billion in May 2011? Skype still has lots of users, but Microsoft has failed on the technology side, fiddling with numerous different Windows and mobile clients and designs, making users unhappy, with poor connections, and absorbing Messenger to no benefit. Lync, Microsoft’s enterprise instant messaging system, has been renamed Skype for Business but still uses different technology.

Still, let’s presume the acquisition works and that LinkedIn continues to grow. Will it make sense for Microsoft? Will it make sense for Microsoft (and LinkedIn’s) customers?

Who are LinkedIn’s customers? In the first quarter of 2016, the quarterly revenue figures looked like this:

Talent solutions (recruitment): $558 million

Marketing solutions (advertising): $154 million

Premium subscriptions (users who pay): $149 million. Of LinkedIn’s 433 million members, just 2 million pay for subscriptions.

Why would you pay for a LinkedIn subscription? I’m speculating, but I’d guess that a paid subscription is excellent value for recruiters and fair value for job seekers, but little value for others. That means the recruitment aspect is if anything understated by the amount in Talent Solutions.

Those other 431 LinkedIn members are not customers. They are users whose presence forms the value of the service to the recruiters.

Microsoft could in principle find other ways to get value out of those users, by making them customers for its productivity offerings. I doubt that that this is the primary intent though. The intent is more about “the magic” of all that lovely data combined with Azure’s powerful analytics capabilities. Somehow that is meant to yield value in unexpected ways.

Google has enormous success with this approach. It services users highly value, such as search, Google Apps, YouTube, Maps, the Android operating system. Then it exploits the presence of those users to offer them contextual advertising. It becomes the portal to your life taking a little cut every time you spend money.

How does this work in a business context? This is not clear to me. What is the synergy between Office 365, which is essentially internal IT services outsourced to a public cloud, and LinkedIn, which is essentially about contact building to find work or sell services? I would say, not all that much. Yes, LinkedIn can be integrated into Office 365 such that it is easier to find freelance help for a need that arises, for example. Making it easier to leave your company by finding another job though is not likely to go down well with Office 365 customers.

Can Microsoft make LinkedIn an essential business destination, like YouTube for video or Google for search, to enable the kinds of contextual opportunities that drive Alphabet’s business? Anything could happen, but it is miles away from that at the moment. Is it the best source for business news? No. Is it the best way to keep in touch with colleagues? No, that’s your internal IT system (could be Office 365), or maybe Facebook or Twitter for social contact. Is it the best way to keep in touch with friends? No, that’s Facebook. And so on.

If you are talking Dynamics CRM, then there you can absolutely see the synergy, but that is not big enough to justify the $26 billion cost.

One of the issues is that LinkedIn is not loved. There is constant bombardment with contact requests which are just a chore. There are emails like this:

which mean little to me because honestly it is not a network I value – being mostly composed of people who have asked to “link in” with me in the hope that I may be useful to them by writing about their stuff. Others tell me they get constant invitations to apply for jobs; IT recruiters can be an aggressive bunch and no doubt it is the same in other professions where there is skills shortage.

In other words, getting from here to a point where LinkedIn is woven into our business lives in a mutually beneficial way looks like a difficult journey.

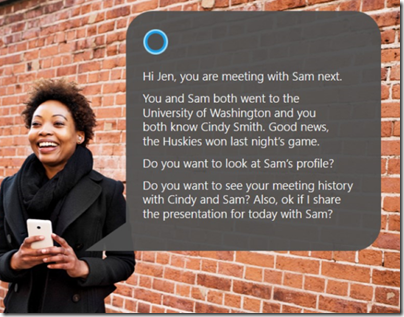

This might explain the lame illustration of how great life will be after the acquisition.

I have a meeting and Cortana is going to give me all kinds of information about the person I am meeting, social as well as professional. This is great for a salesperson going in to make a pitch. It might not be so great for the recipient of that pitch who may want to keep the meeting brief. It raises tricky questions about the overlap between personal and business data.

I recall the Outlook Connector, an add-on to Outlook that surfaced a panel of information about a person drawn mainly from Facebook. I found it intriguing but sometimes uncomfortable, that when someone emailed me for some business reason I would news of their recent holiday or some such.

Privacy and trust

One reason for choosing Microsoft over Google for cloud email and document services is that whereas Microsoft’s main business is in providing IT services, with Google you are always aware that its main business is advertising and that it wants to mine your data. Now that Microsoft wants to create “the world’s first economic graph” that distinction is less sharp. Microsoft wants to mine your data as well, in other words, and possibly not to your advantage. Now we will have to be alert, on Office 365, for checkboxes that say “Share this on my LinkedIn Profile” or “Notify my LinkedIn contacts” or some such.

I was disappointed not to hear more on the privacy and trust issues in the webcast following the announcement. It was left to a question at the end on maintaining the distinction between public and private data. “Nothing gets connected without customers opting in,” said Nadella. I would like to have heard that first. I would also like to be reassured that Nadella means “opting in” rather than “failing to opt out”, which is more the norm in this area.

The new Microsoft

What is the new Microsoft? The LinkedIn deal seems to be significant in several ways. It shows how the company is further tilting towards business rather than consumer customers. And it is not technology. Microsoft is buying data and an internet destination, not technical innovation. To me, Microsoft is at its best when it simplifies and democratizes technology – yes, it can do this, and I’d instance things like Excel, the original Visual Basic, Access, and more recently, things like HoloLens and Windows Phone (the best phone UI). You can even see this in Office 365; it has its complexities but compare it to setting up multiple servers with Active Directory, Exchange and SharePoint and you will get the point.

Right now I am not seeing the magic.