Microsoft’s Windows Phone disaster lurched further towards oblivion last week, when Windows boss Terry Myerson emailed employees with the news that “Today I want to share that we are taking the additional step of streamlining our smartphone hardware business, and we anticipate this will impact up to 1,850 jobs worldwide, up to 1,350 of which are in Finland.”

“Streamlining” is exec-speak for further withdrawal from the mobile phone business.

Microsoft is at times a dysfunctional company and nowhere is this better illustrated than in its mobile devices adventures. The failure of Windows Phone is a self-inflicted wound. Mis-steps include:

- Aiming the first release of Windows Phone 7, in 2010, at the consumer market despite Windows core strength being in business computers

- Launching Windows Phone while failing to do the spadework with operators and retailers to ensure that it was actually widely available

- Using Silverlight as the development platform for Windows Phone and then abandoning Silverlight on Windows and releasing Windows 8 with a different and incompatible development platform

- Promising that Windows Phone would be updated by Microsoft so users could stay up to date, while in fact leaving this to operators who did not care – this applied until April 2014 when the Developer Preview program kicked off, allowing users to update by signing up as developers, subject to hardware constraints

- Long dormant periods while Microsoft went through one of its, “let’s pause while we make huge changes that will be great eventually” phases, such as before Windows Phone 8.0 which introduced the NT kernel and before Windows Mobile 10 which introduced the Universal Windows Platform

Despite all the above, the arrival of a former Microsoft executive at Nokia meant that Windows Phone was adopted by a company that actually understood how to develop and market smartphones. Visibility of Windows Phone at retail greatly improved and technology such as Nokia’s PureView photography gave it an edge in some areas. Windows Phone was also strong for turn by turn driving directions with Here maps.

It was an uphill battle against iPhone and Android, and with Microsoft’s too-slow platform development, but Nokia made some impact and built significant market share in certain territories, though in Europe rather than the USA.

Microsoft acquired Nokia’s devices business in 2014, along with CEO Stephen Elop, and it was here that everything went wrong. Specifically:

The transition period along with the coming Windows 10 resulted in not much happening in terms of new phones or announcements

Steve Ballmer was replaced as Microsoft CEO by Satya Nadella, before the acquisition completed. Ballmer had a strong belief in “Windows everywhere” and the importance of Microsoft not conceding the mobile space to competitors. Nadella came from a server background and believes everything will be fine as long as Microsoft’s server and cloud products are strong.

There was no consensus at Microsoft about whether Windows Phone was a key strategic asset or a waste of time and after running around in circles for a bit the inevitable happened: in June 2015 Nadella cut back the Windows Phone staff, cancelled some forthcoming devices, and parted company with Elop, who presumably had no appetite for presiding over the death of the business he had nurtured.

Myerson’s memo still presents the illusion that Windows Phone has some kind of future. “We’re scaling back, but we’re not out!” he writes. However you cannot be a little bit in the mobile phone business any more than you can be a little bit pregnant. The reason, as Elop announced when Nokia chose Windows Phone, is that you need an ecosystem. No, Continuum (the ability to use a phone like a desktop with an external display) is not an ecosystem. Maybe there will be some specialist business cases where a mobile device running Windows meets the need, but it will be a tiny niche.

This is also the reason why June 2015 was really the date that Windows Phone died, at least in public. Once it became obvious that Microsoft no longer believed in its own mobile platform, there was no hope, and sales suffered accordingly.

Could it have been different? Of course. The Nokia acquisition was not necessarily a bad idea: in theory it gave the hardware the backing of Microsoft’s deep pockets and brought to the company the skills that it lacked in how to make and market phones.

The saga has not been pretty to watch. In particular, the destruction of value in acquiring and then disposing of Nokia is distressing, as is the destruction of value in the Windows Phone operating system itself.

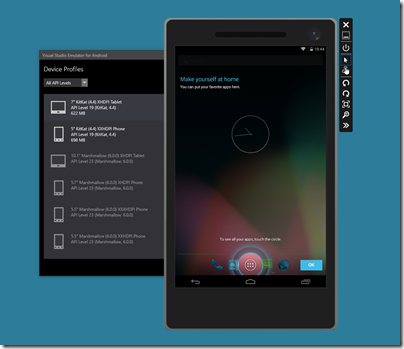

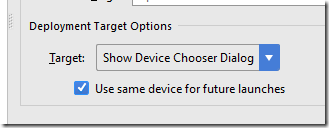

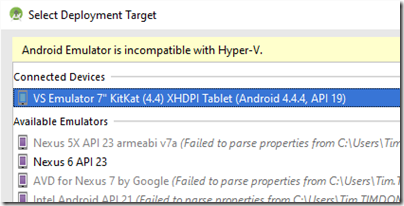

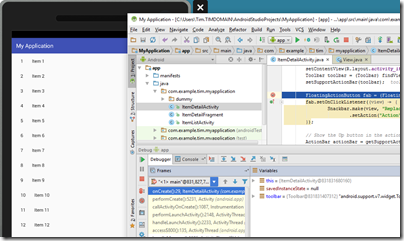

I have used a Windows Phone as my main mobile device for several years, and yes, it has a lot going for it. Navigation is easier than on Android or iOS, performance is good, and the integration with social media was for a while excellent. The camera on a Lumia 1020 remains superb. The development platform is strong, with Visual Studio and C#.

The subject of operating system design is another story; but there is another take on this narrative which looks like this:

Old world: Windows 7, Windows Mobile 6

Lurch towards mobile: Windows 8, Windows Phone 7

Lurch back towards desktop: Windows 10, Windows Mobile 10 with Continuum

Windows 10 is not as good as Windows 8.x on tablets, and Windows Mobile 10 is perhaps not as good as Windows Phone 8.x on mobile. I say perhaps because I don’t hate it; but there is a trade-off with performance and touch-friendliness worse while the capability of the operating system and its apps has improved.

In this way of reading Microsoft’s strategy, the death of Windows Phone is a consequence of the unravelling of former Windows boss Steven Sinofsky’s strategy to make Windows a secure and mobile-friendly platform.

The new Microsoft

That is it then; Microsoft is exiting mobile and trusting in server and cloud, plus a large but declining desktop Windows business, plus applications for other people’s mobile platforms. It is a software company after all.

It is too early though to say whether or not Ballmer was wrong and Nadella right in steering away from Windows everywhere. For sure Google will continue to do all it can to push Android users towards its own cloud services. Apple’s is a more open platform in this sense, because the company has no real equivalent to Office 365 or Azure, but Microsoft is vulnerable here as well. There is also Amazon Web Services to think about, the dominant cloud player, with its own offerings for email, cloud database and so on.

Still, this is the new Microsoft; and from a customer perspective there is good news in that both iOS and Android should be well supported for Microsoft’s services, and that Office 365 and Azure have to compete on technical merit, not just on the basis of integrating nicely with Windows.