Microsoft has shared details of the forthcoming Windows Phone 8 operating system, which is set to be available on devices before the end of 2012.

The improvements are fundamental, and it seems that Microsoft has finally created a mobile platform that has what it takes, technically, to compete in the modern smartphone market. Winning share from competitors is another thing of course; Nokia’s hoped-for third ecosystem is still tiny relative to Apple iOS or Google Android.

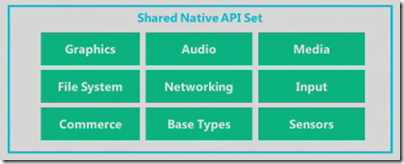

It starts with a change in the core operating system, from Windows CE to Windows 8. The two now share the same kernel, and APIs including Graphics, Audio, Media, File System, Networking, Input, Commerce, Base Types and Sensors. The .NET Framework is also the same. The browser will be Internet Explorer 10.

Silverlight was not mentioned, nor was XNA, though we were told that Windows Phone 7.x apps will run on Windows Phone 8.

The change does enable multi-core support at last. Screen resolution can now go up to 1280 x 768, ready for high-definition displays. There is also support for MicroSD storage, a feature which should have been in the first release.

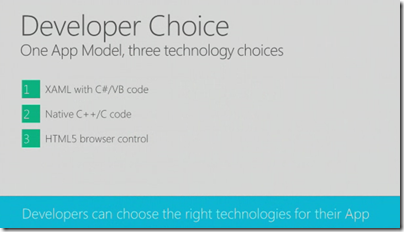

What about Windows RT, the runtime for Metro-style apps in Windows 8? Here is the significant slide from yesterday’s presentation:

This looks similar to Windows RT, which also supports three development models: XAML and .NET, native C/C++ code, and HTML5. It is not quite the same though. One thing I did not hear mentioned was contracts, the communication and file sharing system built into Windows 8, though we were promised “sharing under user control”. Nor did we hear about language “projections”, the layer that lets different languages in Windows 8 call the same Windows Runtime APIs. My guess at the moment is that Windows Phone 8 does not include the Windows Runtime, though it does have much in common with it. The further guess is that the full Windows Runtime will come in Windows Phone 9.

In other words, it seems that Windows Phone 8 will not run apps coded for Windows 8, though we were told that if you code to the XAML and .NET model for apps, and the native code model for games, few changes will be needed. XNA developers should consider a change of direction.

Support for C/C++ is a key feature and one that in my view should have been in the first Windows Phone release. One of the things it enables is official support for SQLite, the cross-platform database engine also found in Mac OS X and numerous other platforms. A good day for SQLite, which pleases me as I am a fan.

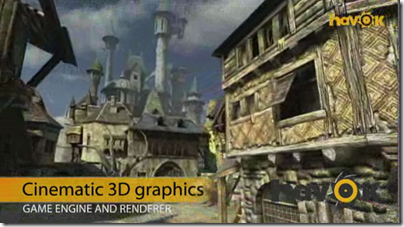

There will also be C/C++ gaming libraries coming to Windows Phone 8, including Havoc:

What else is new? Users will like the new Start screen, which unlike the whole of Windows Phone 8 is also coming to existing devices, which will get a half-way upgrade called Windows Phone 7.8 (7 and 8, geddit?). The innovation in the new Start screen is that any tile can be sized by the user to any of the supported sizes. The smallest size allows four tiles across, so you can make your Windows Phone look more like Android or iOS if you so choose.

What else? Microsoft is not announcing “end-user features” yet, but did promise Nokia offline maps plus turn by turn directions; digital wallet which can be paired with a secure SIM for NFC (near field communications) payment, and deep support for Skype and VOIP so they “feel like any other call”. Apparently operators will love the way the wallet is implemented, because unlike Android it is hooked to the SIM, but I doubt they will be so keen on Skype.

There is an improved speech engine which duly failed to recognise speech input correctly in the first demo, though it worked after that.

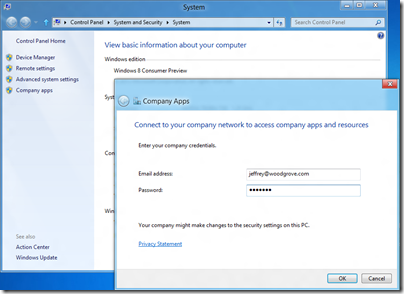

Finally, Microsoft is now talking Enterprise for Windows Phone. There will be bitlocker encryption and enterprise app deployment without Windows store, as well as device management. Think full System Center 2012 integration.

Conclusion? There is disappointment that existing Windows Phone 7 devices are not fully upgradeable, but this is hardly surprising given the changed core. As a platform it is greatly improved, though I would like to see full WinRT included. Despite its poor start, you cannot dismiss this mobile OS as Microsoft continues to use its financial muscle to try and try again.

If it succeeds, will it be too late for Nokia? Maybe, though my hunch is that Microsoft will do what it takes to keep its key mobile partner alive.