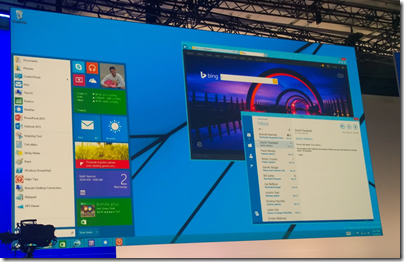

At its Build developer conference in San Francisco, Microsoft has announced a new kind of Windows app: a Universal App. In fact, you can download the latest Visual Studio 2013 update (Update 2 RC) and

A Universal App runs on both Windows Phone 8.1 and Windows 8.1. But what is it really?

The place to start is with the runtime. In Windows Phone 8, Microsoft migrated the kernel in Windows Phone from the cut-down CE version of Windows, to the same kernel used by desktop Windows. However the app runtime in Windows Phone 8 remained Silverlight, Microsoft’s Flash competitor which was originally designed as a browser plug-in.

In Windows Phone 8.1 Microsoft has taken the next logical step, and ported the Windows Runtime (WinRT) to the phone. WinRT is the runtime behind the Metro/Modern/Store App environment introduced in Windows 8.

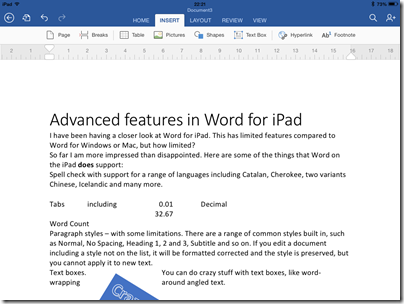

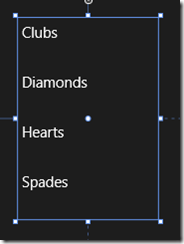

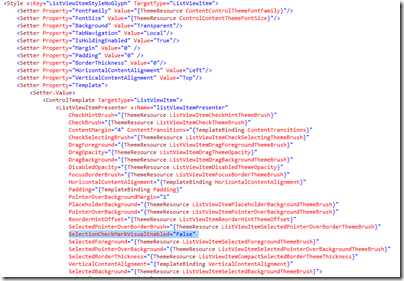

A Universal App runs on WinRT. This means that Windows Phone 8.1 supports the same variety of development options as Windows 8: XAML and C#, XAML and C++, HTML and the WinJS Javascript library (now open source), and DirectX for games.

The port is not 100%; there are some platform-specific APIs. Apparently compatibility is about 90% in terms of APIs available.

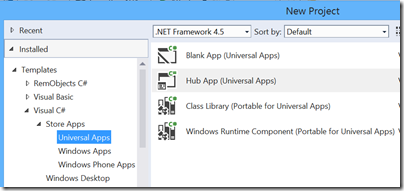

That said, a Universal App is not a universal binary. Apparently you can have a universal binary, but it is not the approach Microsoft is taking. A Universal App is a project type in Visual Studio.

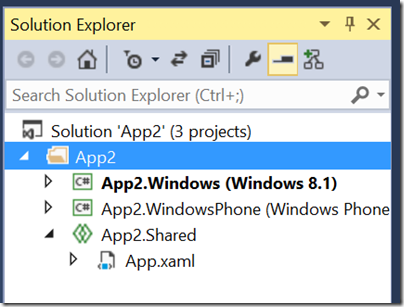

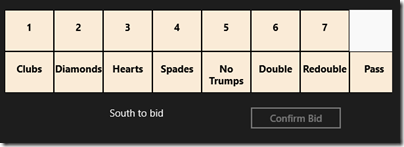

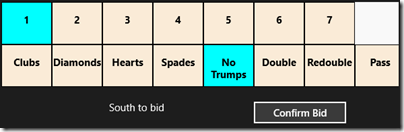

When you create a Universal App you get a project with multiple targets.

By default you get two targets, but we have also seen Xbox One as a target, and conceptually we could see more: maybe Xamarin might extend it to support iOS and Android, for example.

The way this works is that at compile-time any code (which can include XAML and project assets such as images as well as C# code) that is in the Shared project gets merged into the target-specific project.

This means that a Universal App could contain very little shared code, or be almost entirely shared code. This is a developer choice.

Separately, Microsoft has now enabled an app identity to run across multiple Windows platforms in the Store. This means a user can purchase an app once for multiple platforms. However, this is more a business than a technical feature. It would be possible for the developer to offer a multi-platform app in the Store, but keep the development for each platform entirely separate.

That said, the shared WinRT aspect means that code sharing in a Universal App is very feasible. Most if not all non-visual code should work fine, and XAML experts will be able to share most of the UI code as well, thanks to the flexibility built into the XAML UI language.

That is the good bit. There is a problem though. Neither the Windows Phone app platform, nor the Windows 8 app platform have been hugely successful to date, but of the two, Windows Phone has fared better. There are now 500 new apps per day for Windows Phone, we were told here at Build.

Unfortunately, porting those Windows Phone apps to become Universal apps is not easy. Developers have to port their app from Silverlight to WinRT, before they can add a target for Windows 8. They will also need to maintain the old Silverlight app for users with versions of Windows Phone earlier than 8.1. Nokia has promised to offer upgrades for all Windows Phone 8 Lumia models, but that will not the base for all Windows 8 phones out there, and as ever operators have a role here.

Life is easier for Windows 8 app developers who now want to support Windows Phone 8.1; but there are not so many great Windows 8 apps for which Windows Phone users are anxiously awaiting.

Still, the Universal App approach makes perfect sense for the future, once Windows Phone 8.1 is established in the market. It also makes sense for enterprises with internal apps to deploy for mobile and tablet users.