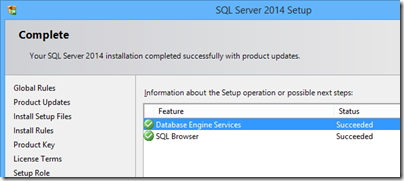

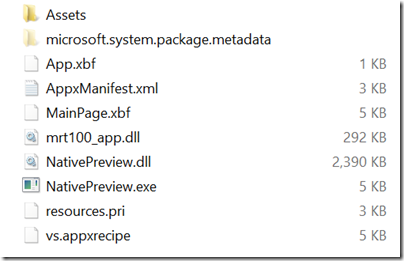

Microsoft designed the Windows Runtime (WinRT, the engine behind the controversial touch-friendly “Metro” user interface in Windows 8) to support three development platforms. These are C++ with XAML (for most GUI apps) or DirectX (for fast games); or C# and XAML; or HTML and JavaScript using the WinJS library for access to Windows-specific functions.

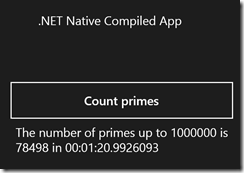

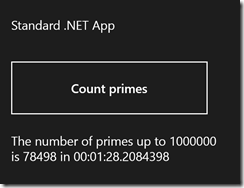

Microsoft’s line is that all three approaches are fine to use, with little performance difference other than that C++ avoids an interop layer. Of course if you have any arbitrary code that runs faster in C++ than in C#, then you will still see that difference in the WinRT environment.

It is also obvious that if you are an HTML and JavaScript expert but know nothing of C# or XAML, you should use WinJS; similarly if you have a lot of C# code to port and know nothing of HTML or JavaScript, C# and XAML chooses itself.

But what if you approach the decision from a neutral perspective. I am going to leave aside the C++ option for the moment as it is more of a leap than C# versus JavaScript. Which is best?

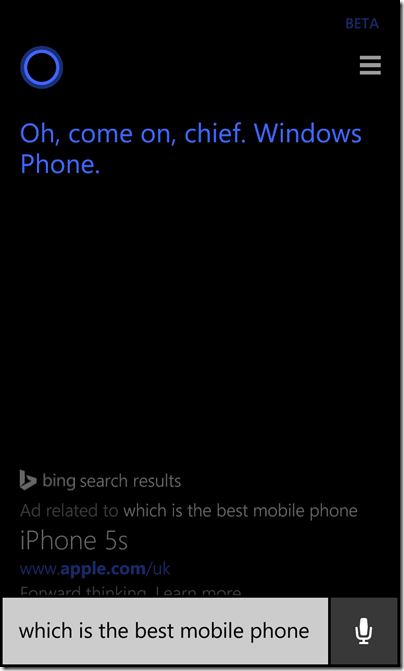

On the WinJS side, a common misconception is that this library is only for Windows. At Build 2014 Microsoft announced that WinJS is now open source, and works on other browsers and devices:

The library has been extended to smaller and more mobile devices with the release of WinJS 2.1 for Windows Phone 8.1, which was announced today at //build. Now that WinJS is available for building apps across Microsoft platforms and devices, it is ready to extend to web apps and sites on other browsers and devices including Chrome, Firefox, iOS, and Android.

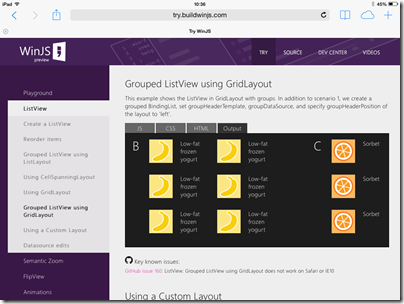

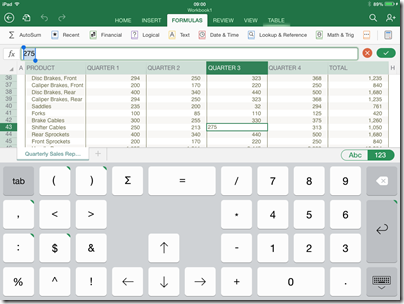

In order to sample this, I went along to try.buildwinjs.com on an iPad. All the things I tried quickly worked fine on iOS.

If you used WinJS to build an app, you could use PhoneGap or Cordova to package it as a native application for the iOS or Android app stores.

A further reflection on this is that some of the WinJS controls which you might have assumed are native WinRT controls instantiated from JavaScript are in fact implemented in CSS and JavaScript. That is an advantage for cross-platform, but does suggest that Microsoft has been busy duplicating the look and feel of XAML controls in HTML and JavaScript, which seems a lot of work and an approach which is bound to result in inconsistencies.

Another snag with this approach – leaving aside the questions of performance and so on which I have not investigated – is that you end up with the distinctive look and feel of a Windows 8 app, which is going to be surprising on these other devices.

C# also has cross-platform potential, thanks to the great work of Xamarin and not forgetting RemObjects C#. Note though that I wrote C# rather than XAML. There is no cross-platform XAML implementation other than the abandoned cross-platform Silverlight efforts, Silverlight for the Mac and Moonlight for Linux. Xamarin expects you to rewrite your UI code for each platform – which may in fact be a good thing, though more effort.

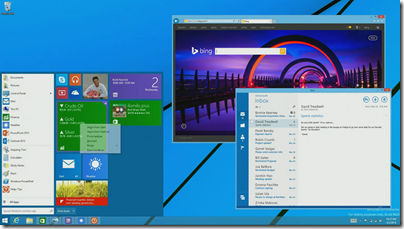

If you are focused on the Windows platform though, it seems to me that the pendulum is swinging away from WinJS and towards C# and XAML. Wordament is an interesting case. This is one of the better games for Windows 8, and also available for Windows Phone, iOS and Android. Originally this was implemented in HTML and JavaScript. The developers have blogged about the choices they made:

Wordament grew up very fast. It seemed like it went from an indie game with a handful of players to a full on Microsoft title with millions of users, on lots of platforms, almost overnight. In that transition we ended up writing lots of code. For instance, in the course of a year we had ports of the Wordament client written in JavaScript, Objective C, C++ and C#. Each one of these ports has its own special issues, build processes and maintenance challenges. At the time, we were still a two person team and Jason and I were struggling to continue to innovate on Wordament, while supporting the “in-market” code bases we had shipped. So we started looking for a solution that would allow us to share more code between all of the platforms we were targeting. Funnily enough, the answer was sitting in our own backyard: C#.

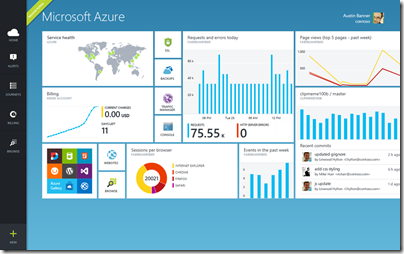

As we looked around at the state of “cross platform development” on Windows, Windows Phone, iOS and Android we started to realize that C# was an excellent choice to target all modern mobile devices. So we did just that. With the help of Visual Studio for Windows and Xamarin for iOS and Android, we started a project to build a single version of Wordament’s source code that could target all the platforms we ship on. This release on Windows 8 marks the end of that journey. All of our clients are now proudly built out of one source tree and in one language. Even our service, which runs on Windows Azure, is built in C#. This is a huge efficiency win for our team of four.

Notable also is that the forthcoming Office for WinRT, previewed at Build, is written in XAML and C++ (according to what I was told). This means XAML will get some love inside Microsoft, which is bound to be good for performance and features.

An advantage of the C# approach is simply that you get to use C#, which is well-liked by developers and with some compelling new features promised in version 6.0, many thanks to the Roslyn project – which also promises a smarter editor in Visual Studio.

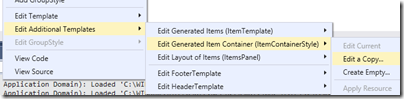

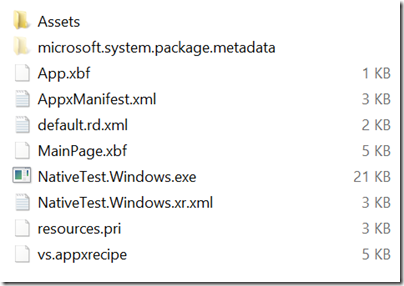

What about XAML? This is harder to love. XML is out of fashion – too verbose, too many angle brackets – and the initial promise of a breakthrough in designer/developer workflow thanks to XAML and MVVM (Model – View – ViewModel, which aims to separate code from user interface design) now seems hollow. I am writing a game in XAML and C# and do not much enjoy the XAML part. One of the issues is that the editing experience is less satisfactory. If you make an error in the XAML, the design view simply blanks out with an “Invalid Markup” error. Further, the integration between the XAML and C# editors is a constant source of problems. Half the time, the C# editor seems to forget the variables declared in XAML, giving you lots of errors and no code completion until you next compile. Even when it is working, a rename refactor in the C# editor will not rename variable references that are within quotes in the XAML, for example property names that are the targets of animations.

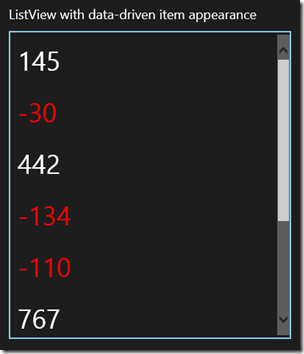

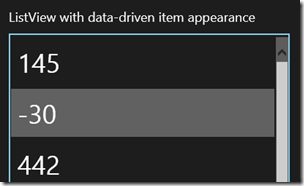

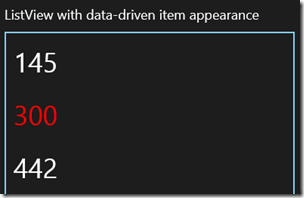

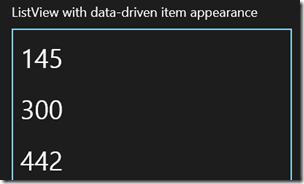

On the plus side, XAML is amazing in what it can do when you work out how. The user interfaces it generates are rich, scalable and responsive. It is way better that the old Win32 GDI-based approach (also used in the Windows Forms .NET API), which is hard to get right for all the combinations of screen sizes and resolutions, and has odd dependencies on system font sizes and dialog units (don’t ask).

Despite the issues with XAML, C# and XAML (or C++ and XAML) is my own preference for targeting the new Windows platform, but I am interested in other perspectives on this.