This book caught my eye because while I like ASP.NET MVC, Microsoft’s modern web application framework, it seems to be badly documented. Even the word “badly” is not quite right; there is lots of documentation, some of high quality, but finding your way around it is challenging, thanks to the many different pieces involved. When I completed an ASP.NET MVC project recently, I found it frustrating thanks to over-reliance on sample projects (hey, here is a an application we did that works, see if you can figure out how we did it), many out of date articles relating to old versions; and the opposite, posts and samples which include preview software that does not seem wise to use in production.

In my experience ASP.NET MVC is both cleaner and faster than ASP.NET Web Forms, the older .NET web framework, but there is more to learn before you can go ahead and write an application.

Professional ASP.NET MVC 5 gives you nearly 600 pages on the subject. It is aimed at a broad readership: the introduction states:

Professional ASP.NET MVC 5 is designed to teach ASP.NET MVC, from a beginner level through advanced topics.

Perhaps that is too broad, though the idea is that the first six chapters (about 150 pages) cover the basics, and that the later chapters are more advanced, so if you are not a beginner you can start at chapter 7.

The main author is Jon Galloway who is a Technical Evangelist at Microsoft. The other authors are Brad Wilson, formerly at Microsoft and now at CenturyLink Cloud; K Scott Allen at OdeToCode, David Matson who is on the ASP.NET MVC team at Microsoft, and Phil Haack formerly at Microsoft and now at GitHub. I get the impression that Haack wrote several chapters in an earlier edition of the book, but did not work directly on this one; Galloway brought his chapters up to date.

Be in no doubt: there are plenty of well-informed ASP.NET MVC people on this team.

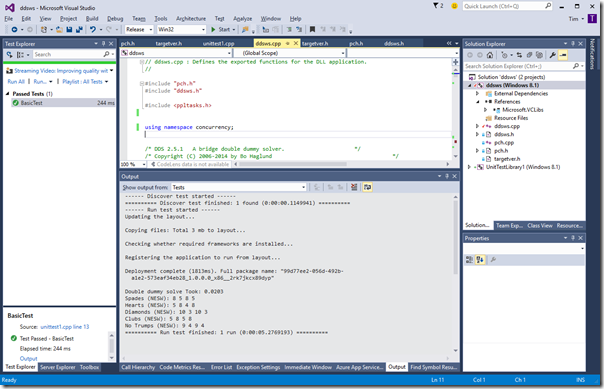

The earlier part of the book uses a sample Music Store application, a version of which is publicly available here. You can also download a tutorial, based on the sample, written by Galloway. The public tutorial however dates from 2011 and is based on ASP.NET MVC 3 and Visual Studio 2010. The book uses Visual Studio 2013.

Chapters 1 to 6, the beginner section, do a decent job of talking you through how to build a first application. There are chapters on Controllers, Views, Models, Forms and HTML Helpers, and finally Data Annotations and Validation. It’s a good basic introduction but if you are like me you will come out with many questions, like what is an ActionResult (the type of most Controller methods)? You have to wait until chapter 16 for a full description.

Chapter 7 is on Membership, Authorization and Security. That is too much for one chapter. It is mostly on security, and inadequate on membership. One of my disappointments with this book is that Azure Active Directory hardly gets a mention; yet to my mind integration of web applications with Office 365 (which uses Azure AD) is a huge feature for Microsoft.

On security though, this is a useful chapter, with handy coverage of Cross-Site Request Forgery and other common vulnerabilities.

Next comes a chapter on AJAX with a little bit on JQuery, client-side validation, and Ajax ActionLinks. Here is the dilemma though. Does it make sense to cover JQuery in detail, when this very popular open source library is widely documented elsewhere? On the other hand, does it make sense not to cover JQuery in detail, when it is usually a vital part of your ASP.NET MVC application?

I would add that this title is poor on design aspects of a web application. That said, I was not expecting much on the design side; but what would help would be coverage of how to work with designers: what is safe to hand over to designers, and how does a typical designer/developer workflow play out with ASP.NET MVC?

I would also like to see more coverage of how to work with Bootstrap, the CSS framework which is integrated with ASP.NET MVC 5 in Visual Studio. I found it a challenge, for example, to discover the best way to change the default fonts and colours used, which is rather basic.

Chapter 9 is on routing, dry but essential background. Chapter 10 on NuGet, the Visual Studio package manager, and a good chapter given how important NuGet now is for most Visual Studio work.

Incidentally, many of the samples for the book can be installed via NuGet. It’s not completely obvious how to do this. I found the best way is to go to http://www.nuget.org and search for Wrox.ProMvc5 – here is the link to the search results. This lists all the packages available; note the package names. Then open the Nuget package manager console and type:

install-package [packagename]

to get the sample.

Chapter 11 is a too-brief chapter on the Web API. I would like to see more on this, maybe even walking through a complete application with clients for say, Windows Phone and a web application – though the following chapter does present a client example using AngularJS.

Chapter 13 is a somewhat theoretical look at dependency injection and inversion of control; handy as Microsoft developers talk a lot about this.

Next comes a very brief introduction to unit testing, intended I think only as a starting point.

For me, the the next two chapters are the most valuable. Chapter 15 concerns extending MVC: you learn about extending models with value providers and model binders; validating models; writing HTML helpers and Razor (the view engine in ASP.NET MVC) helpers; authentication filters and authorization filters. Chapter 16 on advanced topics looks in more detail at Razor, routing, templates, ActionResult and a few other things.

Finally, we get a look at how the Nuget.org application was put together, and an appendix covering some miscellaneous details like what is new in ASP.NET MVC 5.1.

Conclusions

I find this one hard to summarise. There is too much missing to give this an unreserved recommendation. I would like more on topics including ASP.NET Identity, Azure AD integration, Entity Framework, Bootstrap, and more. Trying to cover every developer from beginner to advanced is too much; removing some of the introductory material would have left more room for the more interesting sections. The book is also rather weighted towards theory rather than hands-on coding. At some points it felt more like an explanation from the ASP.NET MVC team on “why we did it this way”, than a developer tutorial.

That said, having those insights from the team is valuable in itself. As someone who has only recently engaged with ASP.NET MVC in a real application, I did find the book useful and will come back to some of those explanations in future.

Looking at what else is available, it seems to me that there is a shortage of books on this subject and that a “what you need to know” title aimed at professional developers would be widely welcomed. It would pay Microsoft to sponsor it, since my sense is that some developers stick with ASP.NET Web Forms not because it is better, but because it is more approachable.