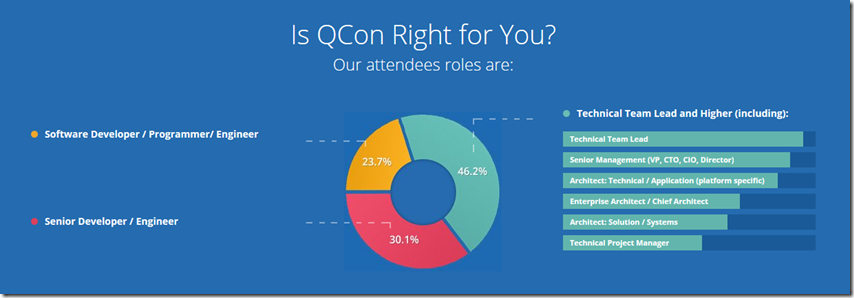

The most significant thing about the Ethics track at QCon London, a software development conference I attended last week, is that it existed. I can recall ethics being discussed at QCon in previous years (including a memorable appeal by Martin Fowler at Thoughtworks about rectifying the gender imbalance in IT) but not a specific track.

Why does ethics matter more today? Ethics has always mattered, but the power of software over our lives is increasing. It is possible be that algorithms at Facebook, YouTube and Twitter influenced the result of the last US election and the UK’s Brexit referendum. Algorithms play a large role in influencing many of choices, what to buy, where to eat, where to stay, which airline to book, which vendor to use.

Software also consumes more of our time than ever, as we constantly check our phones for notifications, play games or read online content.

The increasing importance of AI (Artificial Intelligence) also raises ethical questions. Last week I attended the Re-work AI Assistant Summit, also in London. One of the sessions concerned “Building an AI Friend”, presented by Artem Rodichev from Replika. The demos were impressive, showing how a bot can be engaging and help users to talk about what matters to them. I asked though if the company had thought about ethical issues, for example if a child became attached to a bot without realising it was non-human. The answer I got was in effect a blank look, followed by the statement “we have a minimum age limit of 7”. The company has no announced business model, but I would encourage it to form an ethical policy early as these things are hard to bolt on in retrospect – as Facebook is discovering today, in the aftermath of the exposure of how its personal data is being misused by third parties.

AI is also poised to take over more jobs previously done by people. This could be a great liberator for humanity, or alternatively divide society even more deeply into haves and have-nots.

We need more ethics discussion then; but is it too late? Well, it is never too late to improve matters, but perhaps much harm could have been avoided if the industry had focused on this earlier.

I attended a talk by Alexander Steinhart (a technologist at ThoughtWorks) on the psychologist’s perspective on ethics in technology.

Steinhart talked about addiction. “We all want to unplug, but cannot”, he said.

“Now we are all connected. On average people are nearly three hours online every day. They check phones every 7 to 15 minutes. Many people have difficulties in finding the right balance.”

When is a habit an addiction? When it “gets into the way of your life and you can’t do anything else, and when you try to change behaviour you don’t manage,” said Steinhart, mentioning that “distraction” is identified as a risk by many people today, including teenagers.

Interruptions and distractions are detrimental to our productivity and also a source of stress, he said. Once you are distracted, it takes 20-25 minutes to recover your focus. “Take care that you are not connected all the time.”

Unfortunately we have also developed an “attention economy” where web sites and apps are rewarded for holding our attention and they have evolved to do that effectively.

A great way, apparently, to get us addicted is to have mechanisms that only occasionally reward us. We will try and try again in hope of reward. Lotteries are like this. So are slot machines. So too, says Steinhart, are things like notifications in apps, or the action of pulling down to refresh emails or other feeds. Most of the time we get nothing of value and we know that. But occasionally something really good arrives. The possibility keeps us hooked.

Another difficulty is that humans do not always cope well with abundance. When a previously scarce resource, food for example, becomes abundant, logically what should happen is that we become more discriminating, selecting only the best and discarding the rest. In practice though this is not the case, and we have seen the ascendance of junk food that does us harm.

We now have abundant information. Answering a question that might once have required a trip to the library or several phone calls can now be done in an instance. That is fantastic; but are we coping well? Somehow, instead of becoming more discriminating about the sources and value of available information, humanity is prone to consuming more and more information of low quality, whether that is banal time-wasting or actual falsehoods and information that is intended to deceive or mislead us.

Steinhart argues that we have moved into a new technological era but have not yet learned how to manage it. He draws an analogy with urbanisation; it tool mankind a while to learn how to build cities that were agreeable places in which to live.

Human needs includes some that are will served by today’s technological landscape. We need to experience “all of the different senses, to small, to taste.” We need privacy and solitude. “If you put managers alone for one hour in a room with nothing to do, they make better decisions the rest of the day,” claims Steinhart. We also need conversations, not just connections. “There is so much human interaction that you cannot digitise, like looking someone in the eye” he said.

How does this translate to ethics in technology? We need positive computing and software design that is “aligned with human goals,” he said.

Free and open source software is helpful in this respect, because the goals of the software are aligned with our needs rather then profit.

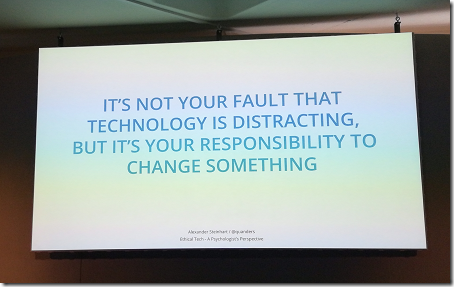

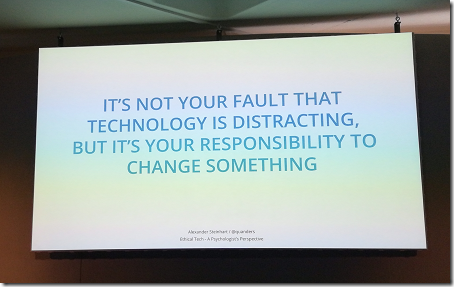

What can software developers do? “It is not your fault that technology is distracting,” said Steinhart, “but it’s your responsibility to change something.”

It is interesting to imagine what software might look like if designed for human needs rather than business interests. Steinhart’s ideas are around making software quieter, designed to get out of our way rather than to interrupt us, smartphones that encourage us to leave them alone, and of course to avoid anti-patterns which feed addiction or deliberately try to trip us up.

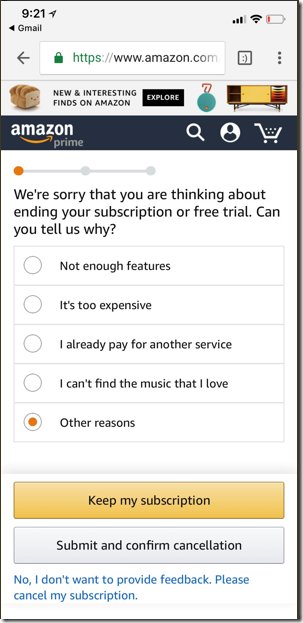

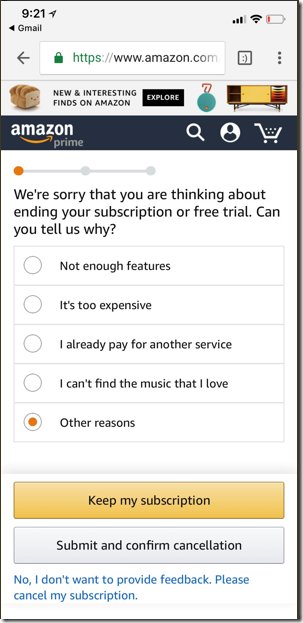

I noticed this tweet today about how an Amazon app behaves when you try to cancel. The user clicks Cancel subscription and gets this:

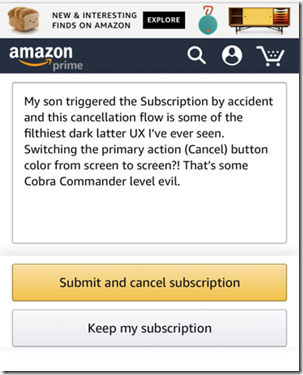

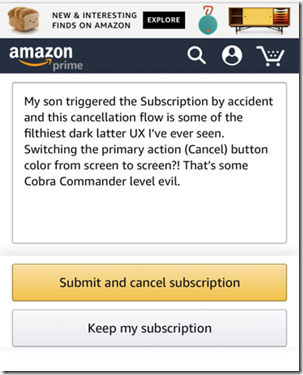

The following screen reverses the button colouring so that if you trained yourself to tap the faint button, you actually do the opposite of what you intend:

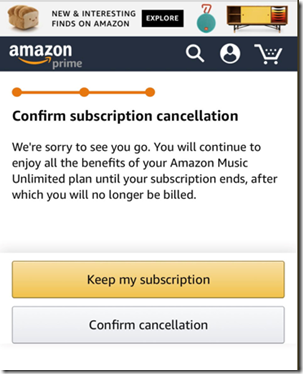

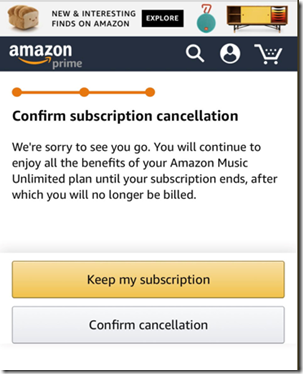

Until the last screen (there’s another one?) where they switch again:

This was not in Steinhart’s talk, but it seems a good example of software designed for the business and not for the user.

I have seen a similar pattern in Amazon’s web checkout where you have to click carefully to avoid being signed up for Amazon’s Prime subscription by accident. Not good.

Ethics and technology

This post is long enough; but there is, I hope, much more to say on this subject.

Despite enjoying Steinhart’s talk and others in the Ethics track, I was not encouraged. We need, of course, regulation as well as more principled businesses, and we do not know what such regulation should look like, nor how to implement it.

One thing though is worth repeating: if as a software developer you are asked to do something that is ethically unacceptable, you should refuse. Professional standards include more than quality of coding.