Apple launched the Mac App Store yesterday and I had a look this morning. It is only available to users of Mac OS X Snow Leopard, where it comes with the latest system update.

It is interesting that Apple has not used iTunes for the App Store, but has developed new client software. Maybe it is coming round to opinion that iTunes has become bloated; it is only for historic reasons that a music player has become an all-purpose app installer.

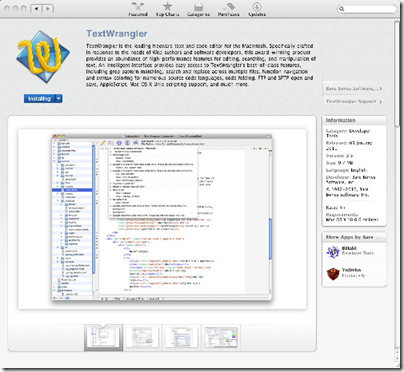

The store itself worked well for me. I picked a free app, TextWrangler, and signed in with my Apple ID. The UI showed Installing, then Installed, and I was done.

The TextWrangler icon appeared in the Dock so I could start the app easily.

What counts is what I did not have to do – reboot, select from setup options, or deal with perplexing error messages.

Users will also like the common-sense licensing, which lets you download and install a purchased app on any Mac you use, controlled by your App Store log-in. I am not sure what happens if you install your app on your friend’s Mac, then sign out of the App Store. There is some link between the app and your Apple ID, because if you copy the application to another Mac it will ask for your sign-in details when you first run it, but I am not clear whether this is checked on every run to deter piracy.

Most important, there is an attractive range of apps at good prices. In the UK, Angry Birds is £2.99, Pinball HD £1.79, and Apple Pages or Keynote £11.99 each. That is less than typical Apple Store shrink-wrap prices. The prices for Pages and Keynote makes the price Microsoft charges for Office look impossibly expensive. Good for customers; but worrying for independent software vendors who want to make a living.

Developers pay $99.00 per year to join the Mac Developer Program and then 30% commission to Apple on every sale. Of course, like the iPhone App Store, apps are subject to Apple’s approval.

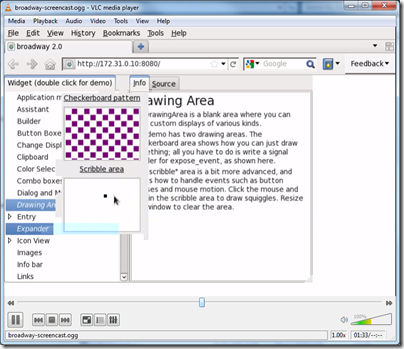

Lest you think it is clever of Apple to invent an app store for the desktop, it is worth noting that the concept is an old one. Linux has delivered free software like this for years, and some distributions have also featured paid app installers integrated into the OS.

So has Microsoft, which has run various varieties of Windows Marketplace over the years, for mobile and desktop applications. Windows Vista shipped with an app store for both Microsoft and third-party apps built-in. It was on the Start menu:

as well as in Control Panel:

On November 1st 2008 Microsoft shut down Windows Marketplace and “transitioned” it to a referral site. There was some angst at the time about the closing of the digital locker, which proved insecure against the threat of corporate mind-changing. It still runs the online Microsoft Store, but this is for Microsoft-only products. For example, you can download Microsoft Songsmith for £25.00:

Why did Windows Marketplace fail? Well, the user experience was poor, it was insufficiently prominent in the Vista user interface, setup could be troublesome. Major Windows app vendors figured out that they would be better off drawing potential customers to their own web sites, where they have full control. As is often the case, Microsoft was conflicted over whether it wanted to drive customers to the online store, or to partner retailers, or to app vendor sites; and the OEMs would have their say as well, when customising Windows for their own PCs.

Another factor is that Windows apps are often not well isolated. Silverlight actually solves this problem – out-of-browser apps are well isolated and secure – but Microsoft does not even ship Silverlight by default with Windows.

The indications are that Microsoft will have another go in Windows 8. Documents leaked last year show an app store. From my post at the time:

There’s a pattern here. Microsoft gets bright idea – Tablet, Windows Marketplace, Passport. Does half-baked implementation which flops. Apple or Google works out how to do it right. Microsoft copies them.