Microsoft announced today that the .NET runtime will be open source and cross-platform for Linux and Mac. There are a several announcements and it is potentially confusing, so here is a quick summary.

The .NET runtime, also known as the CLR (Common Language Runtime) is the virtual machine that runs Microsoft’s C#, F# and Visual Basic .NET languages, performing just –in-time compilation to native code and providing interop between the application code and the operating system APIs. It is distinct from the .NET Framework, which is the library of mostly C# code that underlies application platforms like ASP.NET, Windows Presentation Foundation (WPF), Windows Forms, Windows Communication Foundation and more.

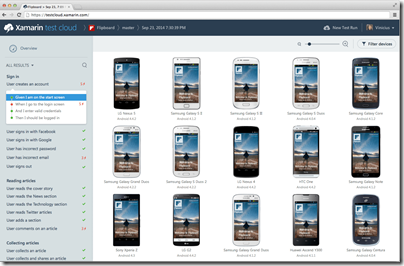

There is is already a cross-platform version of .NET, an open source project called Mono founded by Miguel de Icaza in 2001, not long after the first preview release of C# in 2000. Mono runs on Linux, Mac and Windows. In addition, de Icaza is co-founder of Xamarin, which uses Mono together with its own technology to compile C# for iOS, Android and Mac OS X.

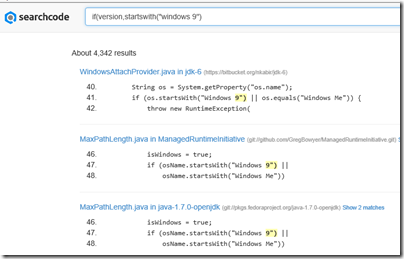

Further, some of .NET is already open source. At Microsoft’s Build conference earlier this year, Anders Hejlsberg made the Roslyn project, the compiler for the next generation of the .NET Runtime, open source under the Apache 2.0 license. I spoke to Hejlsberg about the announcement and wrote it up on the Register here. Note the key point:

Since Roslyn is the compiler for the forthcoming C# 6.0, does that mean C# itself is now an open source language? “Yes, absolutely,” says Hejlsberg.

What then is today’s news? Blow by blow, here are what seems to me the main pieces:

- The CLR itself will be open source. This is the C++ code from which the CLR is compiled.

- Microsoft will provide a full open source server stack for Mac and Linux including the CLR. This will not include the frameworks for client applications; no Windows Forms or WPF. Rather, it is the “.NET Core Runtime” and “.NET Core Framework”. However Microsoft is working with the Mono team which does support client applications so there could be some interesting permutations (bear in mind that Mono also has its own runtime). However Microsoft is focused on the server stack.

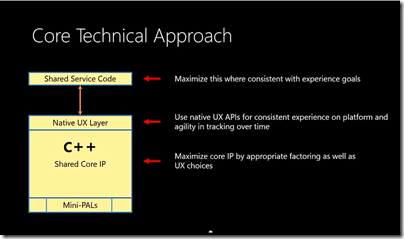

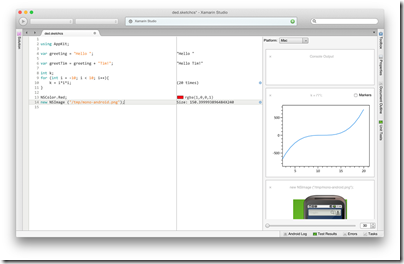

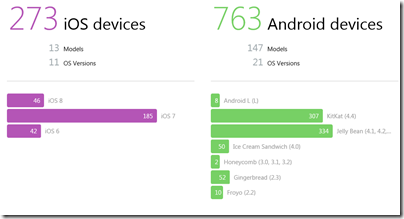

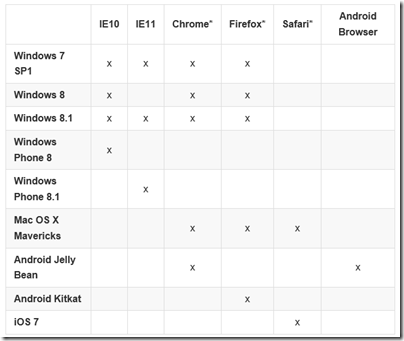

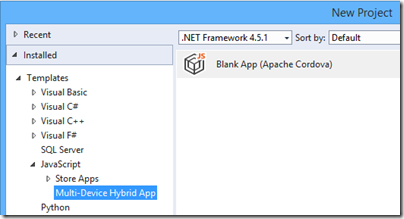

- Microsoft will release C++ frameworks and compilers for iOS and Android, using the open source Clang (C and C++ compiler front-end) and LVVM (code generation back end), but with Visual Studio as the IDE. If you are targeting iOS you will need a Mac with a build agent, or you can use a cloud build service (see below). The Android compiler is available now in preview, the iOS compiler is coming soon. “You can edit and debug a single set of C++ source code, and build it for iOS, Android and Windows,” says Microsoft’s Soma Somasegar, corporate VP of the developer division.

- Microsoft has a new Android emulator for Windows based on Hyper-V. This will assist with Android development using Cordova (the HTML and JavaScript approach also used by PhoneGap) as well as the new C++ option.

- The next Visual Studio will be called Visual Studio 2015 and is now available in preview; download it here.

- There will be a thing called Connected Services to make it easier to code against Office 365, Salesforce and Azure

- A new edition of Visual Studio 2013, called the Community Edition, is now available for free, download it here. The big difference between this and the current Express editions is first that the Community Edition supports multiple target types, whereas you needed a different Express edition for Web applications, Windows Store and Phone apps, and Windows desktop apps. Second, the Community Edition is extensible so that third parties can create plug-ins; today Xamarin was among the first to announce support. There may be some license restrictions; I am clarifying and will update later.

- New Cloud Deployment Projects for Azure enable the cloud infrastructure associated with a project to be captured as code.

- Release Management is being added to Visual Studio Online, Microsoft’s cloud-hosted Team Foundation Server.

- Enhancements to the Visual Studio Online build service will support builds for iOS and OS X

- Visual Studio 2013 Update 4 is complete. This is not a big update but adds fixes for TFS and Visual C++ as well as some new features in TFS and in GPU performance diagnostics.

The process by which these new .NET projects will interact with the open source community will be handled by the .NET Foundation.

What is Microsoft up to?

Today’s announcements are extensive, but with two overall themes.

The first is about open sourcing .NET, a process that was already under way, and the second is about cross-platform.

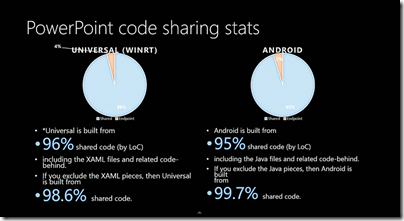

It is the cross-platform announcements that are more notable, though they go hand in hand with the open source process, partly because of Microsoft’s increasingly close relationship with Mono and Xamarin. Note that Microsoft is doing its own C++ compilers for iOS and Android, but leaving the mobile C# and .NET space open for Xamarin.

By adding native code iOS and Android mobile into Visual Studio, Microsoft is signalling real commitment to these platforms. You could interpret this as an admission that Windows Phone and Windows tablets will never reach parity with their rivals, but it is more a consequence of the company’s focus on cloud, and in particular Office 365 and Azure. The company is prioritising the promotion of its cloud services by providing strong tooling for all major client platforms.

The provision of new Microsoft server-side .NET runtimes for Mac and Linux is a surprise to me. The Mac is not much used as a server but very widely used for development. Linux is an increasingly important operating system within the Azure cloud platform.

A side effect of all this is that the .NET Framework may finally fulfil its cross-platform promise, something Microsoft suppressed for years by only supporting it on Windows. That is good news for those who like programming in C#.

The .NET Framework is changing substantially in its next version. This is partly because of the Roslyn compiler, which is itself written in C# and opens up new possibilities for rich refactoring and code transformation; and partly because of .NET Core and major changes in the forthcoming version of ASP.NET.

Is Microsoft concerned that by supporting Linux it might reduce the usage of Windows Server? “In Azure, Windows and Linux are a core part of our platform,” Somesegar told me. “Helping developers by providing a good set of tools and letting them decide what server they run on, we feel is all goodness. If you want a complete open source platform, we have the tools for them.”

How big are these announcements? “I would say huge,” Somasegar told me, “What is shows is that we are not being constrained by any one platform. We are doing more open source, more cross-platform, delivering Visual Studio free to a broader set of people. It’s all about having a great developer offering irrespective of what platform they are targeting or what kind of app they are building.”

That’s Microsoft’s perspective then. In the end, whether you interpret these moves as a sign of strength or weakness for Microsoft, developers will gain from these enhancements to Visual Studio and the .NET platform.