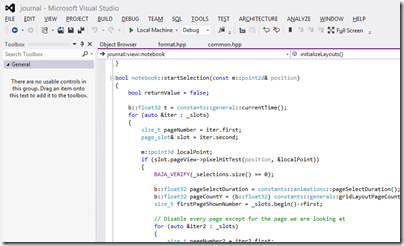

A few quick reflections after writing a rather large review of Visual Studio 2012, Microsoft’s development tool for everything Windows.

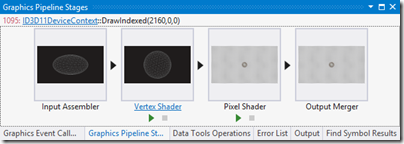

Several things impressed me. The Graphics Diagnostics Tools for Direct3D, for example, is amazing; you can capture a frame, select a pixel, and drill down into why it is the colour it is. See Amit Mohindra’s blog post here. Though admittedly I got “Unable to start the experiment session” on my first go with this; make sure the Debugger Type is set to Native Only.

Graphics is not really my area; but web development is more like it, and I continue to be impressed by what Microsoft has done with Windows Azure. You can go from hitting New Project in Visual Studio to an ASP.NET MVC 4.0 web site up and running on Windows Azure in moments. Even if you add an Azure SQL database into the mix it is not much harder. The experience is slightly spoiled by the fact that the new Azure portal for web sites etc is still in preview and seems to be a bit unreliable; I sometimes get an error when logging in and have to refresh before it works. That is a minor detail though; the actual deployed web sites and applications seem to work fine.

That said, it was also apparent to me that Microsoft’s Azure story has become a little confusing. Want an ASP.NET web app on Azure? Choose between a Web Role, a stateful VM, or a web site. Both web roles and web sites can be scaled quite effectively, thanks to the built in load balancer for web sites. Still, choice is good, as long as the differences are understood. It appears that Microsoft is still backing the web role approach as the most architecturally sound; but web sites are so easy to use and understand that it would not surprise me if they are more successful.

Another hit with me is the SQL Server Data Tools (SSDT), once I understood the difference between DACPACs and BACPACs – a DACPAC encapsulates the schema and logins etc for a database in a single file that you can import elsewhere, whereas a BACPAC also stores the data. The approach in SSDT is that a database schema is just a bunch of SQL scripts, and that if you manage it that way it makes a lot of sense in terms of version control, schema comparisons, deployment and maintenance.

On the ALM side I am impressed with Team Foundation Server Express, which is genuinely easy to install and lights up most of the key features of Microsoft’s ALM platform, though it does not handle the full SharePoint team portal or all the reporting features. Cloud hosting is also an option for TFS and that also worked OK for me, though with occasional delays as my code crossed the internet.

I hesitate slightly with TFS though. It feels like a heavyweight solution, whereas most developers like lightweight solutions. I know that open source tools like git and subversion only do a fraction of what you can do with TFS; but they also never keep me waiting.

I also wonder whether TFS simply creates too many artefacts. Work items seem to multiply rapidly as you use the system, which is good for traceability but could also become a bit of a bureaucratic nightmare if you have team members who make every action into a thing that needs comments and deadlines and links to source code and so on.

I guess it is like any other tool; it will work well for a team that already works well, but will not solve problems for a team that is already a bit dysfunctional.

I had not looked at Microsoft’s modelling featurs for a while; I was interested to discover new code generation features in the UML diagramming tools.

I am slowly beginning to understand what Microsoft is doing with apps for SharePoint. Get this: Microsoft is moving SharePoint 2013 towards being more of a service than a platform; you do not build apps on SharePoint; you build apps that use SharePoint services. This means you can at last develop SharePoint apps without having SharePoint installed on the same box as Visual Studio (thank goodness). And you can build SharePoint apps with PHP or Java as well as ASP.NET, because they are calling SharePoint, not running on it. Makes sense.

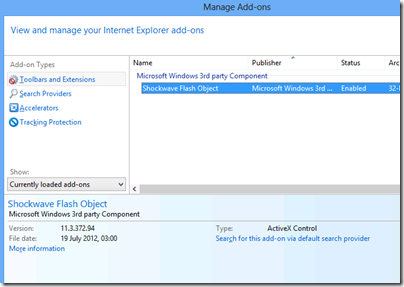

So what is not to like? There are a few puzzles, like the way Visual C++ has fallen behind in standards compliance despite the presence of Herb Sutter at Microsoft.

I also still find the whole XAML/Visual Studio/Blend thing a bit of a struggle. One day I will open up Blend, Microsoft’s XAML designer, and it will all fall into place as a natural and quick way to build a user interface, but it has not happened yet. I have also heard that developers should find the designer in Visual Studio enough; but at best it is rather slow and a little unpredictable.

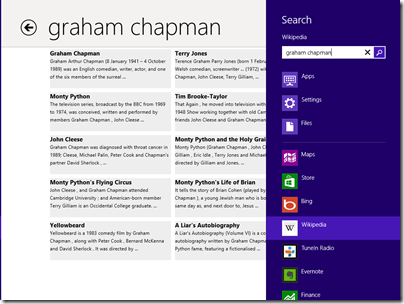

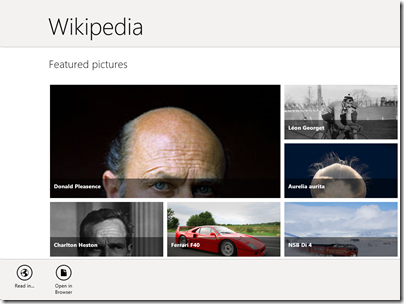

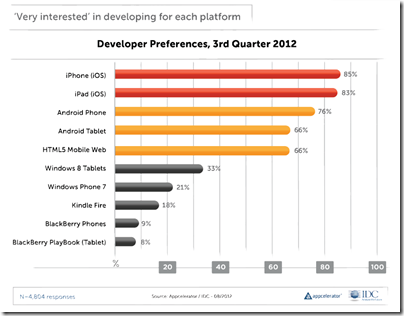

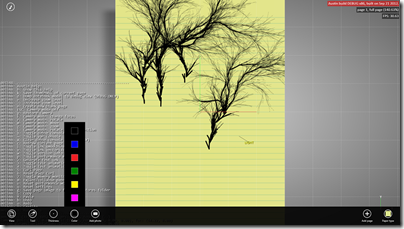

Otherwise the tools for Windows Store apps seem decent to me, though I have heard that advanced developers are finding some issues; not surprising considering how new a platform it is. It is a distinctive platform, and my sense it that while there is a lot to like, developers need time to get the best from it, and there is also scope for Microsoft to improve it, maybe a few refinements in Windows 8 SP1?

Considering its scope, Visual Studio was relatively stable in my tests, though I did once get it into a state where it froze every time I tried to debug an application; fixed by a reboot (sigh).

I do not mind the monochrome user interface; I do not like it especially but it is something you get used to and do not notice after a short time.

Overall? Few people will use everything that is in Visual Studio and of course I have missed out most of it in the above, but it is a mighty achievement and still an asset to Microsoft’s platform.