This is a book about pervasive data collection and its implications. The author, April Falcon Doss, is a lawyer who spent 13 years at the US National Security Agency (NSA), itself an organization controversial for phone-tapping and other covert surveillance practices. Disturbing though that is, one of Doss’s observations is that “in democratic countries … the government doesn’t have nearly as much data as private companies do.” She argues that government-held data is less troubling since its usage is well regulated, unlike privately held data – though these safeguards do not apply in authoritarian regimes.

Government use then is just one piece of something much bigger, the colossal amount of personal data gathered on so much of what we do, our buying habits, what we search for on the internet, our health, our location, our contacts, tastes and preferences, all tracked, stored, and used in ways that we might not expect. Most of the book simply describes what is happening, and this will be eye-opening to anyone who has not followed the growth of data collection and its use in marketing and advertising over the last twenty years or so. Doss describes how a researcher analyzed his iPhone activity and found that “within seven days, the phone had exported data via 5,400 hidden app trackers.” – and Google’s Android is even worse.

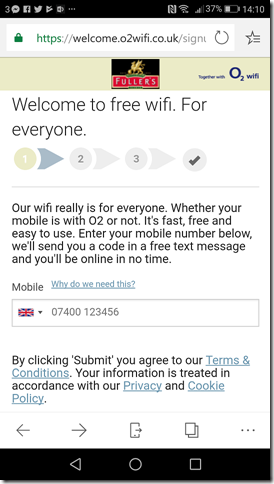

How much do we care and how much should we care? Doss looks at this question which to me is of particular interest. We like getting stuff for free, like social media, search, maps and directions; but how aware are we of hidden costs like compromised privacy and would we be willing to pay in other ways? Studies on the subject are contradictory; humans are not very logical on the matter, and it depends exactly how the trade-off between privacy and cost is presented. The tech giants know this and in general we easily succumb to the temptation to hand over personal information when signing up for free services.

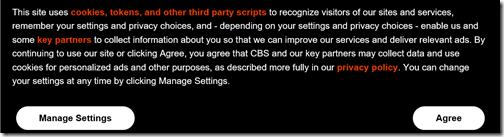

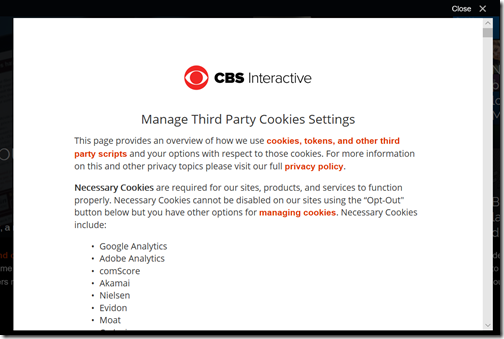

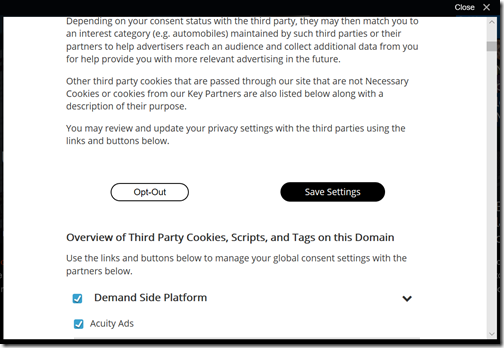

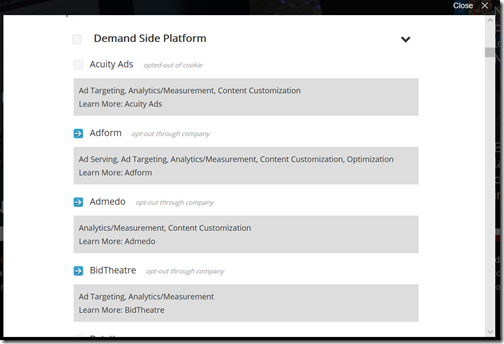

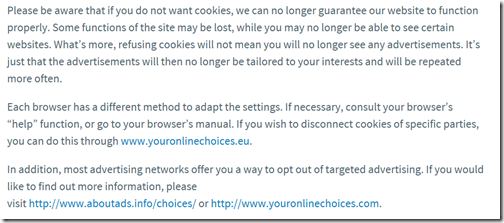

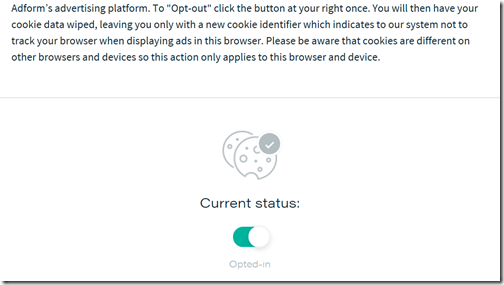

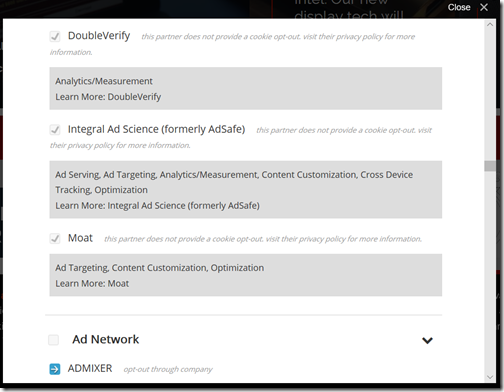

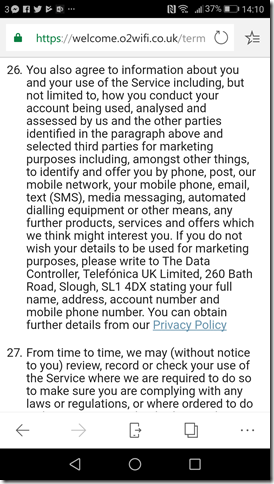

Doss makes some excellent and succinct points, as when she writes that “privacy policies offer little more than a fig leaf of user notice and consent since they are cumbersome to read, difficult to understand, and individuals have few alternatives when it comes to using the major digital platforms.” She also takes aim at well-intended but ineffective cookie legislation – which have given rise to the banners you see, especially in the EU, inviting you to accept all manner of cookies when you visit a web site for the first time. “A great deal of energy and attention has gone into drafting and implementing cookie notice laws,” she says. “But it is an open question whether anyone’s privacy has actually increased.”

She also observes that we are in uncharted territory. “It turns out that all of us have been unwitting participants in a multifaceted, loosely designed program of unregulated research,” she writes.

Personally I agree that the issue is super-important and deserves more attention than it gets, so I am grateful for the book. There are a couple of issues though. One is that the reason personal data gathering has escalated so fast is that we’ve seen benefits – like free services and personalisation of advertising which reduces the amount of irrelevant material we see – but the harms are more hidden. What are the harms? Doss does identify some harms, such as reduced freedom in authoritarian regimes, or higher prices for things like Uber transport when algorithms decide what offers to show based on our willingness to pay. I would like to have seen more attention paid though to the most obvious harm of the moment, the fact that abuse of personal data and social media may have resulted in political upheavals like the election of Donald Trump as US president, or the result of the Brexit referendum in the UK. Whatever your political views, those who value democracy should be concerned; Doss gives this matter some attention but not as much as it merits, in my opinion.

Second, the big question is what can be done; and here the book is short of answers. Doss ends up arguing that we have passed the point of no return in terms of data collection. “The real challenge lies in creating sufficient restrictions to rein in the human tendency to misuse information for purposes that we’ve collectively decided are unacceptable in society,” she writes, acknowledging that how we do so remains an open question.

She says that her ambitions for the book become more modest as the research continued, ending with the hope that she has provided “a catalogue of risks and relevant questions, along with a useful framework for thinking about the future” which “may spark further, future discussions.”

Fair enough, but I would like to have seen more practical suggestions. Should we regulate more? Should Google or Facebook be broken up? As individuals, does it help if we close social media accounts and become more wary about the data that we give away?

Nevertheless I welcome this thought-provoking book and hope that it does help to stimulate the future debate for which the author hopes.

BenBella Books (3 Nov. 2020)