I rashly agreed to create a small web application that uploads files into Azure storage. Azure Blob storage is Microsoft’s equivalent to Amazon’s S3 (Simple Storage Service), a cloud service for storing files of up to 200GB.

File upload performance can be an issue, though if you want to test how fast your application can go, try it from an Azure VM: performance is fantastic, as you would expect from an Azure to Azure connection in the same region.

I am using ASP.NET MVC and thought a sample like this official one, Uploading large files using ASP.NET Web API and Azure Blob Storage, would be all I needed. It is a start, but the method used only works for small files. What it does is:

1. Receive a file via HTTP Post.

2. Once the file has been received by the web server, calls CloudBlob.UploadFile to upload the file to Azure blob storage.

What’s the problem? Leaving aside the fact that CloudBlob is deprecated (you are meant to use CloudBlockBlob), there are obvious problems with files that are more than a few MB in size. The expectation today is that users see some sort of progress bar when uploading, and a well-written application will be resistant to brief connection breaks. Many users have asynchronous internet connections (such as ADSL) with slow upload; large files will take a long time and something can easily go wrong. The sample is not resilient at all.

Another issue is that web servers do not appreciate receiving huge files in one operation. Imagine you are uploading the ISO for a DVD, perhaps a 3GB file. The simple approach of posting the file and having the web server upload it to Azure blob storage introduces obvious strain and probably will not work, even if you do mess around with maxRequestLength and maxAllowedContentLength in ASP.NET and IIS. I would not mind so much if the sample were not called “Uploading large files”; the author perhaps has a different idea of what is a large file.

Worth noting too that one developer hit a bug with blobs greater than 5.5MB when uploaded over HTTPS, which most real-world businesses will require.

What then are you meant to do? The correct approach, as far as I can tell, is to send your large files in small chunks called blocks. These are uploaded to Azure using CloudBlockBlob.PutBlock. You identify each block with an ID string, and when all the blocks are uploaded, called CloudBlockBlob.PutBlockList with a list of IDs in the correct order.

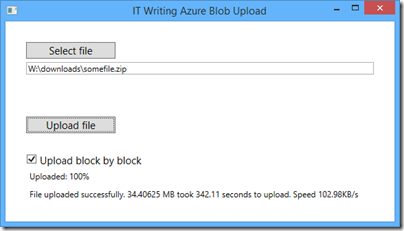

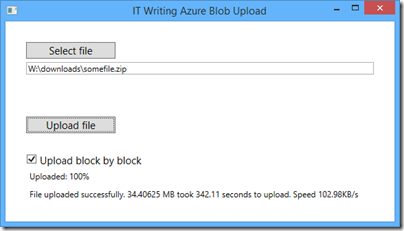

This is the approach taken by Suprotim Agarwal in his example of uploading big files, which works and is a great deal better than the Microsoft sample. It even has a progress bar and some retry logic. I tried this approach, with a few tweaks. Using a 35MB file, I got about 80 KB/s with my ADSL broadband, a bit worse than the performance I usually get with FTP.

Can performance be improved? I wondered what benefit you get from uploading blocks in parallel. Azure Storage does not mind what order the blocks are uploaded. I adapted Agarwal’s sample to use multiple AJAX calls each uploading a block, experimenting with up to 8 simultaneous uploads from the browser.

The initial results were disappointing. Eventually I figured out that I was not actually achieving parallel uploads at all. The reason is that the application uses ASP.NET session state, and IIS will block multiple connections in the same session unless you mark your ASP.NET MVC controller class with the SessionStateBehavior.ReadOnly attribute.

I fixed that, and now I do get multiple parallel uploads. Performance improved to around 105 KB/s, worthwhile though not dramatic.

What about using a Windows desktop application to upload large files? I was surprised to find little improvement. But can parallel uploading help here too? The answer is that it should happen anyway, handled by the .NET client library, according to this document:

If you are writing a block blob that is no more than 64 MB in size, you can upload it in its entirety with a single write operation. Storage clients default to a 32 MB maximum single block upload, settable using the SingleBlobUploadThresholdInBytes property. When a block blob upload is larger than the value in this property, storage clients break the file into blocks. You can set the number of threads used to upload the blocks in parallel using the ParallelOperationThreadCount property.

It sounds as if there is little advantage in writing your own chunking code, except that if you just call the UploadFromFile or UploadFromStream methods of CloudBlockBlob, you do not get any progress notification event (though you can get a retry notification from an OperationContext object passed to the method). Therefore I looked around for a sample using parallel uploads, and found this one from Microsoft MVP Tyler Doerksen, using C#’s Parallel.For.

Be warned: it does not work! Doerksen’s approach is to upload the entire file into memory (not great, but not as bad as on a web server), send it in chunks using CloudBlockBlob.PutBlock, adding the block ID to a collection at the same time, and then to call CloudBlockBlob.PutBlockList. The reason it does not work is that the order of the loops in Parallel.For is indeterminate, so the block IDs are unlikely to be in the right order.

I fixed this, it tested OK, and then I decided to further improve it by reading each chunk from the file within the loop, rather than loading the entire file into memory. I then puzzled over why my code was broken. The files uploaded, but they were corrupt. I worked it out. In the following code, fs is a FileStream object:

fs.Position = x * blockLength;

bytesread = fs.Read(chunk, 0, currentLength);

Spot the problem? Since fs is a variable declared outside the loop, other threads were setting its position during the read operation, with random results. I fixed it like this:

lock (fs)

{

fs.Position = x * blockLength;

bytesread = fs.Read(chunk, 0, currentLength);

}

and the file corruption disappeared.

I am not sure why, but the manually coded parallel uploads seem to slightly but not dramatically improve performance, to around 100-105 KB/s, almost exactly what my ASP.NET MVC application achieves over my broadband connection.

There is another approach worth mentioning. It is possible to bypass the web server and upload directly from the browser to Azure storage. To do this, you need to allow cross-origin resource sharing (CORS) as explained here. You also need to issue a Shared Access Signature, a temporary key that allows read-write access to Azure storage. A guy called Blair Chen seems to have this all figured out, as you can see from his Azure speed test and jazure JavaScript library, which makes it easy to upload a blob from the browser.

I was contemplating going that route, but it seems that performance is no better (judging by the Test Upload Big Files section of Chen’s speed test), so I should probably be content with the parallel JavaScript upload solution, which avoids fiddling with CORS.

Overall, has my experience with the Blob storage API been good? I have not found any issues with the service itself so far, but the documentation and samples could be better. This page should be the jumping off point for all you need to know for a basic application like mine, but I did not find it easy to find good samples or documentation for what I thought would be a common scenario, uploading large files with ASP.NET MVC.

Update: since writing this post I have come across this post by Rob Gillen which addresses the performance issue in detail (and links to working Parallel.For code); however I suspect that since the post is four years old the conclusions are no longer valid, because of improvements to the Azure storage client library.