The audiophile world (small niche though it is) is buzzing with a renewed interest in high resolution audio, now to be known as HRA.

See, for example, Why the Time is Right for High-Res Audio, or Sony’s new Hi-Res USB DAC System for PC Audio, or Gramophone on At last high-resolution audio is about to go mainstream, or Mark Fleischmann on CD Quality Is Not High-Res Audio:

True HRA is not a subtle improvement. With the best software and hardware, a good recording, and good listening conditions, it is about as subtle as being whacked with a mallet, and I mean that in a good way. It is an eye opener. In lieu of “is that all there is?” you think “wow, listen to what I’ve been missing!” … The Compact Disc format is many good things but high-res it is not. It has a bit depth of 16 and a sampling rate of 44.1 kHz. In other words, it processes a string of 16 zeroes and ones 44,100 times per second. Digitally speaking, this is a case of arrested development dating back to the early 1980s. We can do better now.

As an audio enthusiast, I would love this to be true. But it is not. Fleischmann appears to be ignorant of the Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem, which suggests that the 16-bit/44.1 kHz CD format can exactly reproduce an analogue sound wave from 20–22,050 Hz and with a dynamic range (difference between quietest and loudest signal) of better than 90Db.

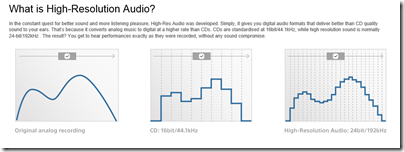

Yes there are some ifs and buts, and if CD had been invented today it would probably have used a higher resolution of say 24-bit/96 Khz which gives more headroom and opportunity for processing the sound without degradation; but nevertheless, CD is more than good enough for human hearing. Anyone who draws graphs of stair steps, or compares CD audio vs HRA to VHS or DVD vs Blu-Ray, is being seriously misleading.

Yes, Sony, you are a disgrace. What is this chart meant to show?

If shows that DACs output a bumpy signal it is simply false. If it purports to show that high-res reproduces an analogue original more accurately within the normal audible range of 20-20,000 Hz it is false too.

As an aside, what non-technical reader would guess that those huge stair steps for “CD” are 1/44,100th of a second apart?

The Meyer-Moran test, in which a high-res original was converted to CD quality and then compared with the original under blind conditions (nobody could reliably tell the difference), has never been debunked, nor has anyone conducted a similar experiment with different results as far as I am aware.

You can also conduct your own experiments, as I have. Download some samples from SoundKeeper Recordings or Linn. Take the highest resolution version, and convert it to CD format. Then upsample the CD quality version back to the high-resolution format. You now have two high-res files, but one is no better than CD quality. Can you hear the difference? I’ve yet to find someone who can.

Read this article on 24/192 Music Downloads … and why they make no sense and watch the referenced video for more on this subject.

Still, audio is a mysterious thing, and maybe in the right conditions, with the right equipment, there is some slight difference or improvement.

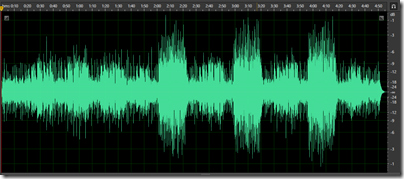

What I am sure of, is that it will be nowhere near as great as the improvement we could get if CDs were sensibly mastered. Thanks to the loudness wars, few CDs come close to the audio quality of which they are capable. Here is a track for a CD from the 80s which sounds wonderful, Tracy Chapman’s debut, viewed as a waveform in Adobe Audition:

And here is a track from Elton John’s latest, The Diving Board:

This everything louder than everything else effect means that the sound is more fatiguing and yes, lower fidelity, than it should be; and The Diving Board is far from the worst example (in fact, it is fairly good by today’s standards).

It is not really the fault of recording engineers. In many cases they hate it too. Rather, it is the dread of artists and labels that their sales may suffer if a recording is quieter (when the volume control is at the same level) than someone else’s.

Credit to Apple which is addressing this to some extent with its Mastered for iTunes initiative:

Many artists and producers feel that louder is better. The trend for louder music has resulted in both ardent fans of high volumes and backlash from audiophiles, a

controversy known as “the loudness wars.” This is solely an issue with music. Movies, for example, have very detailed standards for the final mastering volume of a film’s

soundtrack. The music world doesn’t have any such standard, and in recent years the de facto process has been to make masters as loud as possible. While some feel that overly

loud mastering ruins music by not giving it room to breathe, others feel that the aesthetic of loudness can be an appropriate artistic choice for particular songs or

albums.Analog masters traditionally have volume levels set as high as possible, just shy of oversaturation, to improve the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). With digital masters, the goal

is to achieve the highest gain possible without losing information about the original file due to clipping.With digital files, there’s a limit to how loud you can make a track: 0dBFS. Trying to increase a track’s overall loudness beyond this point results in distortion caused by

clipping and a loss in dynamic range. The quietest parts of a song increase in volume, yet the louder parts don’t gain loudness due to the upper limits of the digital format.

Although iTunes doesn’t reject files for a specific number of clips, tracks which have audible clipping will not be badged or marketed as Mastered for iTunes.

Back to my original point: what is the point of messing around with the doubtful benefits of HRA, if the obvious and easily audible problem of excessive dynamic compression is not addressed first?

None at all. The audio industry should stop trying to mislead its customers by appealing to the human instinct that bigger numbers must mean better sound, and instead get behind some standards for digital music that will improve the sound we get from all formats.