Google announced at its I/O conference in June 2014 that Android apps are coming to its Chrome OS. Earlier this month product managers Ken Mixter and Josh Woodward announced that the first four Android apps are available in the Chromebook app store: Duolingo, Evernote, Sight Words and Vine.

I delayed posting about this until I found the time to investigate a little into how it works. I fired up an Acer C720 and installed Evernote from the Chrome web store (in addition to Evernote Web which was already installed).

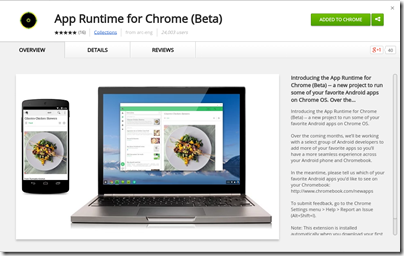

When you install your first Android app, Chrome installs the App Runtime for Chrome (Beta) (ARC) automatically.

Incidentally, I found Evernote slightly odd on Chromebook since it is runs in a window although the app is designed to run full screen, as it would on a phone or tablet. This caught me out when I went to settings, which looks like a dialog, and closed it with the x at the top right of the window. Of course that closes the app entirely. If you want to navigate the app, you have to click the back arrow at top left of the window instead.

But what is the App Runtime for Chrome? This seems to be an implementation of the Android runtime for NaCl (Native Client), which lets you run compiled C and C++ code in the browser. If you browse the parts of ARC which are open source, you can see how it implements the Android Open Source Project (AOSP) for arch-nacl: a virtual processor running as a browser extension.

Not all of ARC is open source. The docs say:

Getting Started with ARC Open Source on Linux

=============================================

A small set of shared objects can be built which are part of ARC currently.

A fully running system cannot currently be built.

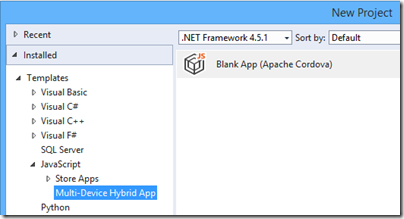

It is early days, with just four apps available, ARC in beta, and developers asked to contact Google if they are interested in having their Android apps run on Chrome OS. However, an independent developer has already ported ARC to desktop Chrome:

ARChon runtime lets you run unlimited number of Android APKs created with

chromeos-apkon Chrome OS and across any desktop platform that supports Chrome.

The desktop version is unstable, and apps that need Google Play services run into problems. Still, think of it as a proof of concept.

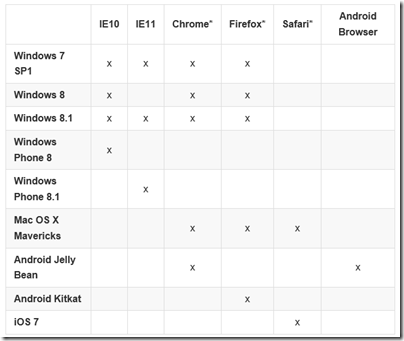

In particular, note that this is Android Runtime for Chrome, not Android Runtime for Chrome OS. Google is targeting the browser, not the operating system. This means that ARC can, if Google chooses, become an Android runtime for every operating system where Chrome runs – with the exception, I imagine, of Chrome for iOS, which is really a wrapper for Apple’s web browser engine and cannot support NaCl, and Chrome for Android which does not need it.

Imagine that Google gets ARC running well on Windows and Mac. What are the implications?

The answer is that Android will become a cross-platform runtime, alongside others such as Flash (the engine in Adobe AIR) and Java. There has to be some performance penalty for apps written in Java for Android running in an Android VM in the browser; but NaCl runs native code and I would expect performance to be good enough.

This would make Android an even more attractive target for developers, since apps will run on desktop computers as well as on Android itself.

Might this get to the point where developers drop dedicated Windows or Mac versions of their apps, arguing that users can just run the Android version? An ARC app will be compromised not only in performance, but also in the way it integrates with the OS, so you would not expect this to happen with major apps. However, it could happen with some apps, since it greatly simplifies development.