I’m in Seattle airport waiting to head home – so here are some quick reflections on Microsoft’s Professional Developers Conference 2010.

Let’s start with the content. There was a clear focus on two things: Windows Azure, and Windows Phone 7.

On the Azure front, the cloud platform, Microsoft impressed. Features are being added rapidly, and it looks solid and interesting. The announcements at PDC mean that Azure provides pretty much the complete Windows Server platform, should you want it. You will get elevated privileges for complete control over a server instance; and full IIS functionality including support for multiple web sites and the ability to install modules. You will also be able to remote desktop into your Azure servers, which is going to make Windows admins feel more comfortable with Azure.

The new virtual machine role is also a big deal, even though in some ways it goes against the multi-tenanted philosophy by leaving the customer responsible for patches and updates. Businesses with existing virtual servers can simply move them to Azure if they no longer wish to run their own hardware. There are also existing tools for migrating physical servers to virtual.

I asked Bob Muglia, president of server and tools at Microsoft, whether having all these VMs maintained by customers and potentially compromised with malware posed a security threat to the platform. He assured me that they are fully isolated, and that the main danger is to the customer who might consume unexpected amounts of bandwidth.

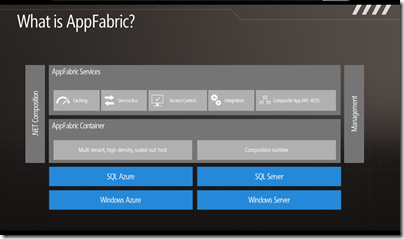

Simply running on an Azure VM does not take full advantage of the platform though. It makes more sense to hook into Azure services such as SQL Azure, or the non-relational storage services, and deploy to Azure web or worker roles where Microsoft take care of maintenance. There is also a range of middleware services called AppFabric; see here for a few notes on these.

If there was one gap in the Azure story at PDC, it was a lack of partner announcements. Microsoft says there are more than 20,000 applications running on Azure, but we did not hear much about them, or about notable large customers embracing Azure. There is still a lot of resistance to the cloud among customers. I asked some attendees at lunch whether they expect to use Azure; the answer was “no, we have our own datacenter”.

I think the partner announcements will come. Microsoft is firmly behind Azure now, and it makes sense for its customers. I expect Azure to succeed; but whether it will do well enough to counter-balance the cost to Microsoft of migration away from on-premise servers is an open question.

Alongside Azure, though hardly mentioned at PDC, is the hosted application business originally called BPOS and now called Office 365. This is not currently hosted on Azure, though Muglia told me that most of it will in time move there. There are some potential synergies here, for example in Azure workflow applications that handle SharePoint forms or documents.

Microsoft’s business is primarily based on partners selling Windows hardware and licenses for on-premise or client software. Another open question is how easily the company can re-orient itself to be a cloud platform and services company. It is a massive shift.

What about Windows Phone? Microsoft has some problems here, and they are not primarily to do with the phone itself, which is decent. There are a few issues over the design of the launch devices, and features that are lacking initially. Further, while the Silverlight and XNA SDK forms a strong development platform, there is a need for a native code SDK and I expect this will follow at some point.

The key issue though is that outside the Microsoft bubble there is not much interest in the phone. Google Android meets the needs of the OEM hardware and operator partners, being open and easily customised. Apple owns the market for high-end devices with the design quality and ease of use that comes from single-vendor control of the whole stack. The momentum behind these platforms is such that it will not be easy for Microsoft to grab much market share, or attention from third-party app developers. It deserves to do well; but I will not be surprised if it under-performs relative to its quality.

There was also some good material to be found on the PDC sidelines, as it were. Andes Hejlsberg presented on new asynchronous features coming in C# 5.0, which look like a breakthrough in making concurrent programming safer and easier. He also showed a bit of Microsoft’s work on compiler as a service, which has huge potential. Patrick Smaccia has an enthusiastic report on the C# presentation. Herb Sutter gave a brilliant talk on lambdas.

The PDC site lets you stream pretty much all the sessions and seems to work very well. The player application is written in Silverlight. Note that there are twice as many sessions as appear in the schedule, since many were pre-recorded and only show in the full session list.

Why did Microsoft run such a small event, with only around 1000 attendees? I asked a couple of people about this; the answer seems to be partly as a cost-saving measure – it is much cheaper to run an event on the Microsoft campus than to hire an external venue and pay transport and expenses for all the speakers and staff – and partly to emphasise the virtual aspect of PDC, with a global audience tuning in.

This does not altogether make sense to me. Microsoft is still generating a ton of cash, as we heard in the earnings call at the event, and PDC is a key opportunity to market its platform to developers and influencers, so it should not worry too much about the cost. Second, you can do virtual as well as physical; they are not alternatives. You get more engagement from people who are actually present.

One of the features of the player is that you see how many are currently streaming the content. I tuned into Mark Russinovich’s excellent session on Azure – he says he has “drunk the cloud kool-aid” – while it was being streamed live, and was surprised to see only around 300 virtual attendees. If that figure is accurate, it is disappointing, though I am sure there will be thousands of further views after the event.

Finally, what about all the IE9/HTML 5 vs Silverlight discussion generated at PDC? Clearly Microsoft’s messaging went badly awry here, and frankly the company has only itself to blame. It cannot be surprised if after making a huge noise about how IE9 forms a great client for web applications, standards-based and integrated with Windows, that people question what sort of role is envisaged for Silverlight. It did not help that a planned session on Silverlight futures was apparently cancelled, probably for innocent reasons such as not being quite ready to show, but increasing speculation that Silverlight is now getting downplayed.

Microsoft chose to say nothing on the subject, other than some remarks by Bob Muglia to freelance journalist Mary-Jo Foley which seem to confirm that yes, Silverlight is no longer Microsoft’s key technology for cross-platform web applications.

If that was not quite the message Microsoft intended, then why not clarify the matter to press, myself included, as we sat in the press room on Microsoft’s campus?

My take is that while Silverlight is by no means dead, it seems destined for a lesser role than was once envisaged – a shame, as it is an excellent cross-platform .NET client.