Google CEO Eric Schmidt gave a keynote address at the Mobile World Congress yesterday, which is worth watching if you have an interest in the future of technology or, well, human life.

The talk was an informative and open insight into Google’s future direction. It was centred on mobile; but since Google now regards the mobile phone as the primary device for how we interact with the world, that was no limitation. Google is putting mobile first, said Schmidt, because it is the meeting point for the three things that matter: computing, connectivity and the cloud. He believes that phones will replace credit cards, for example, as they are smarter and more secure for financial transactions.

Google’s strategy is to combine the near-unlimited power of server-side computing with its database of human behaviour, to create devices that are “like magic. All of a sudden there are things you can do that were not previously possible.”

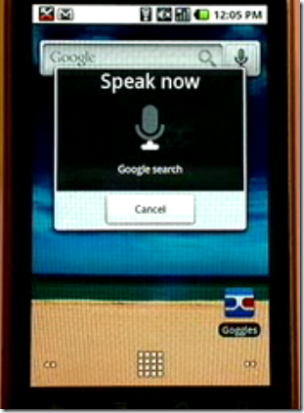

He gave an illuminating example: Google voice search. You speak into your phone, and Google transcribes your voice and performs a search. Voice recognition is nothing new, but the difference in the Google demo is that it works. Here’s how. The problem with voice recognition is that one word sounds very like another, especially since we do not speak with precision and every voice varies. Computers cannot understand exactly what we say, but they can use dictionaries to come up with a set of possibilities for what we said, one of which is likely to be correct.

The next step is the brilliant one. Google takes this set of possible phrases and compares it to recent Google searches. If one of them matches a popular search, then it is likely to be what you said. Bingo. Google now does this in four languages, with German demonstrated for the first time yesterday.

It works on the assumption that humans are not very original. We tend to do similar things, and to be interested in similar things. Therefore, as Schmidt noted, if you are a tourist walking around a city with your location-aware phone, Google does not only know where you are; it also has a good idea of where you will go next.

Another cool demo is for image recognition. We saw this in two guises. In one, you hold up your phone and do an image search using the camera as input. Result: information about the building you are looking at. [Or maybe the person? Hmm.]

In another demo, you point the camera at your foreign-language menu as you ponder which incomprehensible dish might be one you could eat. Back comes the translation in your own language.

Note that these demonstrations are not really about super-powerful phones, but rather about the other two factors mentioned above, the power of cloud computing combined with a vast database of knowledge.

Schmidt’s blind spot is that he does not really see privacy as an issue. He mentions it from time to time; but he is clear that he regards the trade-off, that we give our personal data to Google in return for these cool services, as worth it. I posted a remarkable quote yesterday. Here’s another one, from late on in the address:

Google will know more about the customer because it benefits the customer if we know more about them.

What Schmidt fails to do is to extrapolate the implications for stuff other than cool services. One is what happens if that huge database is used dishonourably. Another is the huge competitive advantage it gives to Google versus everyone else; Google has this data, but rest of us do not. A third is how that data could be used in ways that disadvantage us. An example is in insurance. Insurance is about pooling risk. The more data insurance companies have about you, the more accurately they can assess the risk, which means a wider range of premiums. If by some mechanism insurance companies are able to analyse Google’s data to assess risk, they can refuse to insure, or charge high penalties, for the higher risks. We won’t necessarily enjoy that, because it means more us may find it impossible to get the insurance we want at a price we can afford.

Google’s business strategy

That’s the technical side. What are Google’s business plans? Schmidt made some interesting comments here as well, many of them in the question and answer session.

Google does not plan to become a mobile operator. Schmidt received some fairly hostile questions on this topic. Since Google positions operators as dumb pipes, stealing their talk minutes and insisting on an open web for services, who will invest in infrastructure? Schmidt denies positioning operators as dumb pipes, but does not leave them room for much other than infrastructure; he says they might have a role in financial transactions.

How do we (both Google and the rest of us) make money? Two main areas, according to Schmidt. One is advertising. He says that online advertising spend is currently one tenth of the total, and that this proportion must grow since “consumers are moving from offline to online.” In addition, mobile advertising will be huge since you can target location as well as using other data to personalise ads. “The local opportunity is much larger, and largely unexplored,” he says.

The other big opportunity is apps. The number of apps that need to be installed locally is constantly diminishing, he says, leaving great potential for new cloud-based applications and services.

As for Google, Schmidt says it wants to be part of everything you do:

We want to have a little bit of Google in every transaction on the internet

Thought-provoking stuff, and a force that will be hard to resist.

So who can compete with Google? Making equally capable phones is easy; building an equally good database of human intentions not so much, particularly since it is self-perpetuating: the more we all use Google, the better it gets.

No wonder Microsoft is piling money into Bing, with limited success so far. No wonder Apple’s Steve Jobs is concerned:

On Google: We did not enter the search business, Jobs said. They entered the phone business. Make no mistake, they want to kill the iPhone. We won’t let them, he says. Someone else asks something on a different topic, but there’s no getting Jobs off this rant. I want to go back to that other question first and say one more thing, he says. This don’t be evil mantra: "It’s bullshit." Audience roars.