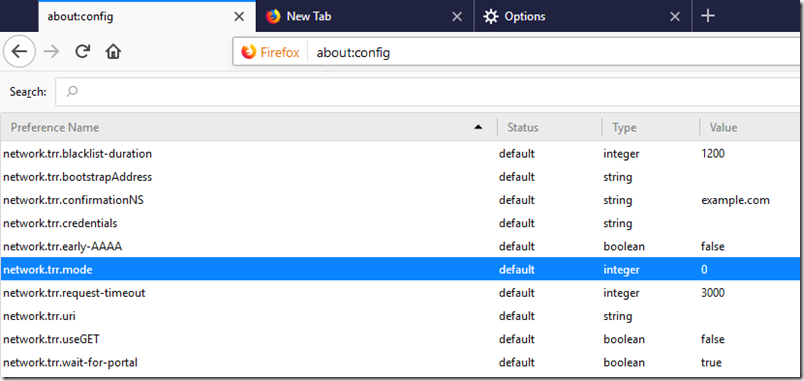

Mozilla is proposing to make DNS over HTTPS default in Firefox. The feature is called Trusted Recursive Resolver, and currently it is available but off by default:

DNS is critical to security but not well understood by the general public. Put simply, it resolves web addresses to IP addresses, so if you type in the web address of your bank, a DNS server tells the browser where to go. DNS hijacking makes phishing attacks easier since users put the right address in their browser (or get it from a search engine) but may arrive at a site controlled by attackers. DNS is also a plain-text protocol, so DNS requests may be intercepted giving attackers a record of which sites you visit. The setting for which DNS server you use is usually automatically acquired from your current internet connection, so on a business network it is set by your network administrator, on broadband by your broadband provider, and on wifi by the wifi provider.

DNS is therefor quite vulnerable. Use wifi in a café, for example, and you are trusting the café wifi not to have allowed the DNS to be compromised. That said, there are further protections, such as SSL certificates (though you might not notice if you were redirected to a secure site that was a slightly misspelled version of your banking site, for example). There is also a standard called DNSSEC which authenticates the response from DNS servers.

Mozilla’s solution is to have the browser handle the DNS. Trusted Recursive Resolver not only uses a secure connection to the DNS server, but also provides a DNS server for you to use, operated by Cloudflare. You can replace this with other DNS servers though they need to support DNS over HTTPS. Google operates a popular DNS service on 8.8.8.8 which does support DNS over HTTPS as well as DNSSEC.

While using a secure connection to DNS is a good thing, using a DNS server set by your web browser has pros and cons. The advantage is that it is much less likely to be compromised than a random public wifi network. The disadvantage is that you are trusting that third-party with a record of which sites you visit. It is personal data that potentially could be mined for marketing or other reasons.

On a business network, having the browser use a third-party DNS server could well cause problems. Some networks use split DNS, where an address resolves to an internal address when on the internal network, and an external address otherwise. Using a third-party DNS server would break such schemes.

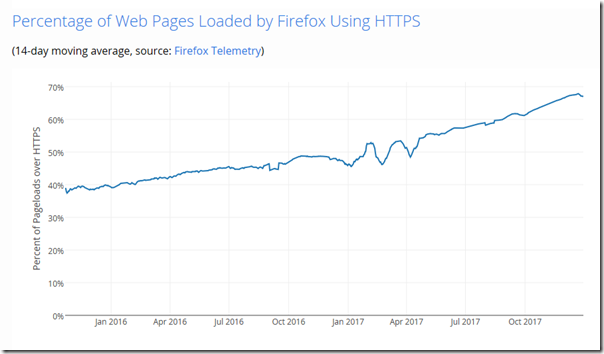

Few will use this Firefox feature unless it is on by default – but that is the plan:

You can enable DNS over HTTPS in Firefox today, and we encourage you to.

We’d like to turn this on as the default for all of our users. We believe that every one of our users deserves this privacy and security, no matter if they understand DNS leaks or not.

But it’s a big change and we need to test it out first. That’s why we’re conducting a study. We’re asking half of our Firefox Nightly users to help us collect data on performance.

We’ll use the default resolver, as we do now, but we’ll also send the request to Cloudflare’s DoH resolver. Then we’ll compare the two to make sure that everything is working as we expect.

For participants in the study, the Cloudflare DNS response won’t be used yet. We’re simply checking that everything works, and then throwing away the Cloudflare response.

Personally I feel this should be opt-in rather than on by default, though it probably is a good thing for most users. The security risk from DNS hijacking is greater than the privacy risk of using Cloudflare or Google for DNS. It is worth noting too that Google DNS is already widely used so you may already be using a big US company for most of your DNS resolving, but probably without the benefit of a secure connection.