In the beginning there was the Professional Developers Conference (PDC) – the first was in 1992. They were fantastic events, with deep dives into the innards of Windows and how to develop applications on Microsoft’s platform. Much of the technology presented was in early preview and often did not work quite right; some things that were presented never made it to production, famous examples including “Hailstorm” also known as .NET My Services, and the WinFS file system originally slated for Windows Vista.

These events seemed to be a critical part of Microsoft’s development cycle. Internally teams would ready their latest stuff for a PDC session, which was then adapted and re-presented at other events around the world.

Then PDC kind-of morphed into Microsoft Build, the first of which took place in September 2011. Unlike PDC, Build was specifically focused on Windows, and was originally associated with Windows 8 and its new app platform, WinRT. Part of the vision behind Windows 8 was that it would have a strong app ecosystem and Build was about enthusing and informing developers about the possibilities.

As it turned out, the Windows 8 app ecosystem was a bit of a disaster for various reasons. Microsoft had another go with UWP (Universal Windows Platform) in Windows 10. Build in April 2015 was an amazing event, where the company appeared to be going all-out to make UWP on both desktop and mobile a success. Not only was the platform itself being enhanced, but we also got Project Centennial (deliver desktop applications via the Store), Project Astoria (compile Android apps to UWP) and Project Islandwood (compile iOS code for UWP).

Just a few months later the company made a huge about-turn. CEO Satya Nadella’s Aligning Engineering to Strategy memo signalled the beginning of the end for Windows Phone, and the departure of Stephen Elop and the dismantling of the Nokia devices acquisition. That was the end of the universal part of UWP.

Project Astoria was scrapped. The Windows Bridge for iOS (Project Islandwood) still just about exists, but its core rationale (get iOS apps to Windows Phone) is now irrelevant.

Nadella steered the company instead towards “the intelligent cloud” and to date that strategy has been successful, with impressive growth for Office 365 and Microsoft Azure.

Microsoft has announced Build 2018, in early May, I find it intriguing, given the history of Build, that Windows is not currently mentioned on the event’s home page. In the page description metadata it says:

Microsoft Build 2018, Seattle, WA May 7-9, 2018. Microsoft’s ultimate developer conference focused on cloud, artificial intelligence, mixed reality, and more.

In the main text of the page, about the only specific topics mentioned are these:

Take in keynotes by Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella and other visionaries behind the Intelligent Cloud and Intelligent Edge

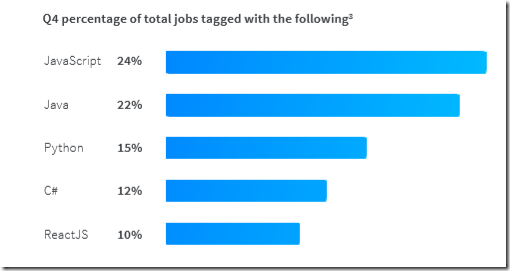

That sounds like a focus on Azure and AI/ML/IoT/Big Data cloud services, and on mobile and IoT devices. It is a long way removed from the original concept of Build as all about Windows and its application platform.

Windows remains important to Microsoft, and to all of us who use it day to day. Still, if you think about cutting-edge software development today, Windows desktop applications are probably not the first thing to come to mind, nor UWP for that matter.

This being the case, it does make sense for the company to focus on its cloud services at Build, and on diverse mobile platforms through what is now an amazing range of cross-platform tools in Visual Studio.

Of course there will in fact also be Windows stuff at Build, including Windows and HoloLens Mixed Reality, Cortana skills and UWP improvements.

Still, if you can only get to one big Microsoft event in the year, Ignite in September is now a bigger deal and closer to the heart of the new (or current) Microsoft.

Let me add that these Microsoft events, whether Build or PDC, have on occasion seen some stunning announcements. Examples include the unveiling of C# and the .NET Framework, the 2003 Longhorn reveal (yes it all turned to dust), Windows 7 in 2008, and Windows 8 in 2011.

I would like to think that the company still has the capacity to surprise and amaze us; but it must be admitted that the current Build pitch is rather unexciting. Google I/O, incidentally, is on at the same time.