Microsoft’s Jason Zander has published an account of what went wrong yesterday, causing failure of many Azure services for a number of hours. The incident is described as running from 0.51 AM to 11.45 AM on November 19th though the actual length of the outage varied; an Azure application which I developed was offline for 3.5 hours.

Customers are not happy. From the comments:

So much for traffic manager for our VM’s running SQL server in a high availability SQL cluster $6k per month if every data center goes down. We were off for 3 hrs during the worst time of day for us; invoicing and loading for 10,000 deliveries. CEO is wanting to pull us out of the cloud.

So what went wrong? It was a bug in an update to the Storage Service, which impacts other services such as VMs and web sites since they have a dependency on the Storage Service. The update was already in production but only for Azure Tables; this seems to have given the team the confidence to deploy the update generally but a bug in the Blob service caused it to loop and stop responding.

Here is the most troubling line in Zander’s report:

Unfortunately the issue was wide spread, since the update was made across most regions in a short period of time due to operational error, instead of following the standard protocol of applying production changes in incremental batches.

In other words, this was not just a programming error, it was an operational error that meant the usual safeguards whereby a service in one datacenter takes over when another fails did not work.

Then there is the issue of communication. This is critical since while customers understand that sometimes things go wrong, they feel happier if they know what is going on. It is partly human nature, and partly a matter of knowing what mitigating action you need to take.

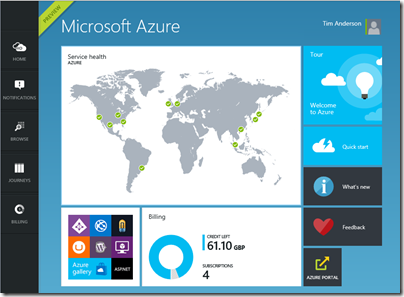

In this case Azure’s Service Health Dashboard failed:

There was an Azure infrastructure issue that impacted our ability to provide timely updates via the Service Health Dashboard. As a mitigation, we leveraged Twitter and other social media forums.

This is an issue I see often; online status dashboards are great for telling you all is well, but when something goes wrong they are the first thing to fall over, or else fail to report the problem. In consequence users all pick up the phone simultaneously and cannot get through. Twitter is no substitute; frankly if my business were paying thousands every month to Microsoft for Azure services I would find it laughable to be referred to Twitter in the event of a major service interruption.

Zander also says that customers were unable to create support cases. Hmm, it does seem to me that Microsoft should isolate its support services from its production services in some way so that both do not fail at once.

Still, of the above it is the operational error that is of most concern.

What are the wider implications? There are two takes on this. One is to say that since Azure is not reliable try another public cloud, probably Amazon Web Services. My sense is that the number and severity of AWS outages has reduced over the years. Inherently though, it is always possible that human error or a hardware failure can have a cascading effect; there is no guarantee that AWS will not have its own equally severe outage in future.

The other take is to give up on the cloud, or at least build in a plan B in the event of failure. Hybrid cloud has its merits in this respect.

My view in general though is that cloud reliability will get better and that its benefits exceed the risk – though when I heard last week, at Amazon Re:Invent, of large companies moving their entire datacenter infrastructure to AWS I did think to myself, “that’s brave”.

Finally, for the most critical services it does make sense to spread them across multiple public clouds (if you cannot fallback to on-premises). It should not be necessary, but it is.