The latest versions of Adobe AIR and Microsoft Silverlight both allow access to native code, but with limitations. The two platforms take a different approach though – here is a quick comparison.

Native code access in AIR

The new version 2.0 of Adobe AIR is just about done. The runtime is available now (as is Flash Player 10.1), but we have to wait until June 15 for the final version of the SDK.

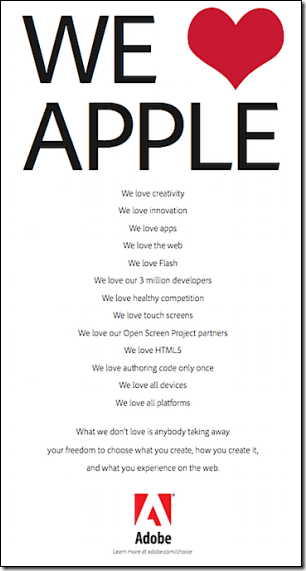

AIR lets you create cross-platform desktop applications that use the Flash runtime. Supported operating systems include Mac, Windows and Linux, and coming soon, Android. Sadly, supported operating systems do not include Apple’s iPhone or iPad.

One of the big new features in AIR 2.0 is access to native code. Of course this breaks cross-platform, unless you create identical native code extensions for all the platforms that AIR supports. Still, the ability to extend AIR without limit using native code is significant. So how do you use it, can you call a DLL or a dynamic shared library? What about COM on Windows, for automating Microsoft Office?

The answer is that you can do all these things, but not easily. There are actually three obvious ways to communicate with native applications in AIR 2.0:

1. Open a document using the default file handler. This is done using the new openWithDefaultApplication function. This is a handy way to open a PDF or Microsoft Office document, but you as the developer have little control over what happens. You do not know which application will open, and cannot control it once it does open.

2. Socket support. Your AIR application can send and receive data over a TCP socket. If you write a native code socket server and install it, you can get access to the local operating system APIs that way.

3. Native process support. This one looks promising. The new NativeProcess class lets you launch a native application and communicate with it via STDIN and STDOUT. Your native application could do anything, of course, such as calling a DLL or using COM, but it must use STDIN and STDOUT to communicate with AIR.

Another limitation is that AIR applications which use this function must be installed with a native installer, rather than by downloading an .AIR file. A further limitation is that auto-update does not work for these applications. You will have to write your own code to check for updates and download an updated installer if necessary.

Native code access in Silverlight

Microsoft Silverlight 4.0 also has the ability to run on the desktop and to call native code – but the native code part only works on Windows, and is restricted to applications that are “Trusted”, which means the user has approved the installation. A trusted Silverlight 4.0 desktop application can call COM via AutomationFactory.CreateObject. Presuming it is successful, your application can call methods on the returned object. If what you really want is to call a DLL, for example, you would have to write a COM DLL (or an application with a COM API) that calls the native DLL.

In addition, Silverlight 4.0 trusted applications have socket support, so that would be another possible approach. However, unlike Adobe AIR 2.0, you cannot simply open a document using the default file handler for its type. That said, it would be trivial to do so using COM and the WScript object, for example. You can also use the browser to do this – see here for an interesting case study from Beat Kiener, who does this with remote documents.

The main limitation of native code access in Silverlight is that it only works on Windows. Even if it does go cross-platform at some point, you would not use COM on Mac or Linux, so some other mechanism will be necessary.

Comparing the two

First, let’s acknowledge that native code interop is not something to use lightly in a cross-platform runtime. If you have to use native code, maybe AIR or Silverlight is not the right choice.

Opening files using the default file handler is a different case, as you can do this without any platform-specific code.

Still, if you can do almost everything in AIR or Silverlight, but need to call a native API for just one or two important features, it may be a reasonable approach.

My immediate observation is that native code interop is easier in Silverlight, though wrecked by being restricted to Windows only. The packaging and updating limitations in AIR, plus being restricted to STDIN and STDOUT, is more arduous than using COM in Silverlight.

Further, it is a shame that neither platform lets you simply call a dynamic library. It would then be relatively easy to write some conditional code to load the appropriate library on different platforms, and many tasks could be accomplished without needing to build and deploy your own native code executable for each platform.

Will you be using native code interop in either AIR or Silverlight? I’d be interested in hearing of examples, and how well it is working for you.