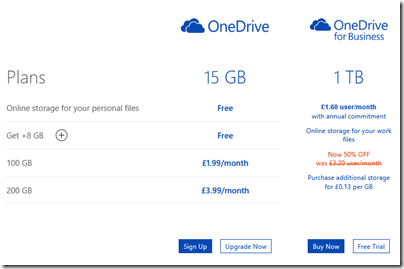

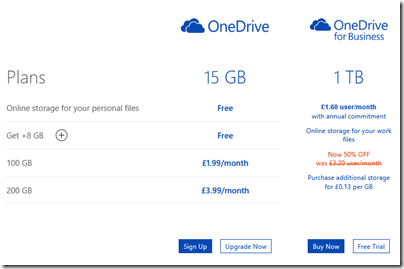

Microsoft’s price plans for additional cloud storage are odd:

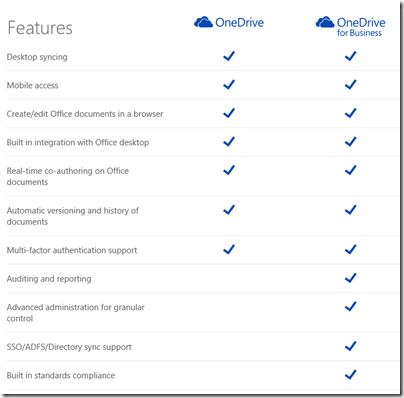

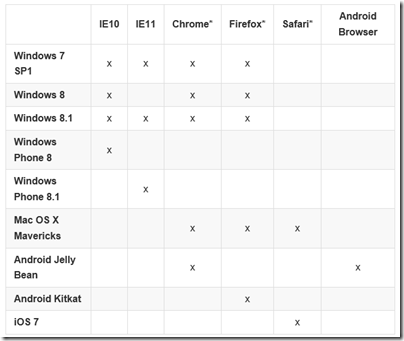

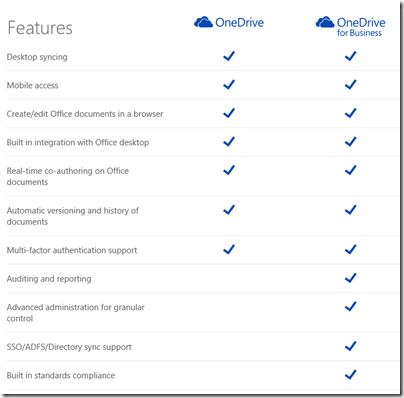

Hmm, £1.60 per month for 1TB or £3.99 for 200GB. Difficult decision? Especially as OneDrive for Business appears to be a superset of OneDrive:

It is not that simple of course (and see below for how you can get 1TB OneDrive for less). The two products have different ancestries. OneDrive was once SkyDrive and before that Windows Live Folders and before that Windows Live Drive. It was designed from the beginning as a cloud storage and client sync service.

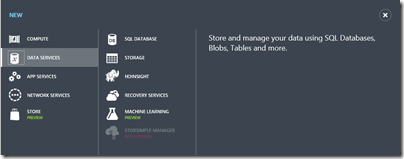

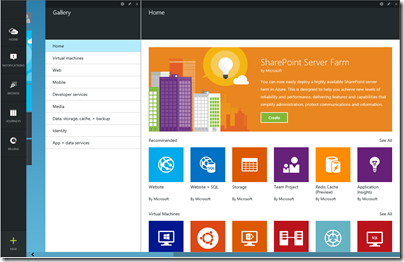

OneDrive for Business on the other hand is essentially SharePoint: team portal including online document storage and collaboration. The original design goal of SharePoint (a feature of Windows Server 2003) was to enable businesses to share Office documents with document history, comments, secure access and so on, and to provide a workplace for teams. See the history here. SharePoint supported a technology called WebDAV (Web Distributed Authoring and Versioning) to allow clients to access content programmatically, and this could be used in Windows to make online documents appear in Windows Explorer (the file utility), but there was no synchronization client. SharePoint was not intended for storage of arbitrary file types; the system allowed it, but full features only light up with Office documents. In other words, not shared storage so much as content management system. Documents are stored in Microsoft SQL Server database.

SharePoint was bolted into Microsoft BPOS (Business Productivity Online Suite) which later became Office 365. In response to demand for document synchronization between client and cloud, Microsoft came up with SharePoint Workspace, based on Groove, a synchronization technology acquired along with Groove Networks in 2005.

I have no idea how much original Groove code remains in the the OneDrive for Business client, nor the extent to which SharePoint Online really runs the same code as the SharePoint you get in Windows Server; but that is the history and explains a bit about why the products are as they are. The OneDrive for Business client for Windows is an application called Groove.exe.

OneDrive and OneDrive for Business are different products, despite the misleading impression given by the name and the little feature table above. This is why the Windows, Mac and Mobile clients are all different and do different things.

OneDrive for Business is reasonable as an online document collaboration tool, but the sync client has always been poor and I prefer not to use it (do not click that Sync button in Office 365). You may find that it syncs a large number of documents, then starts giving puzzling errors for which there is no obvious fix. Finally Microsoft will recommend that you zap your local cache and start again, with some uncertainty about whether you might have lost some work. Microsoft has been working hard to improve it but I do not know if it is yet reliable; personally I think there are intractable problems with Groove and it should be replaced.

The mobile clients for OneDrive for Business are hopeless as DropBox replacements. The iOS client app is particularly odd: you can view files but not upload them. Photo sync, a feature highly valued by users, is not supported. However you can create new folders through the app – but not put anything in them.

Office on iOS on the other hand is a lovely set of applications which use OneDrive for Business for online storage, which actually makes sense in this context. It can also be used with consumer OneDrive or SharePoint, once it is activated.

The consumer version of OneDrive is mostly better than OneDrive for Business for online storage. It is less good for document collaboration and security (the original design goals of SharePoint) but more suitable for arbitrary file types and with a nice UI for things like picture sharing. The Windows and mobile clients are not perfect, but work well enough. The iOS OneDrive client supports automatic sync of photos and you can upload items as you would expect, subject to the design limitations of Apple’s operating system.

Even for document collaboration, consumer OneDrive is not that bad. It supports Office Web Apps, for creating and editing documents in the browser, and you can share documents with others with various levels of permission.

What this means for you:

- Do not trust the OneDrive for Business sync client

- Do not even think about migrating from OneDrive to OneDrive for Business to get cheap cloud storage

- No, you mostly cannot use the same software to access OneDrive and OneDrive for Business

- Despite what you are paying for your Office 365 subscription, consumer OneDrive is a better cloud storage service

- SharePoint online also known as OneDrive for Business has merit for document collaboration and team portal services, beyond the scope of consumer OneDrive

Finally, what Microsoft should do:

- Create a new sync client for OneDrive for Business that works reliably and fast, with mobile apps that do what users expect

- Either unify the technology in OneDrive and OneDrive for Business, or stop calling them by the same name

I do understand Microsoft’s problem. SharePoint has a huge and complex API, and Microsoft’s business users like the cloud-hosted versions of major server applications to work the same way as those that are on premise. However SharePoint will never be a optimal technology for generic cloud storage.

If I were running Office 365, I think I would bring consumer OneDrive into Office 365 for general cloud storage, and I would retain SharePoint online for what it is good at, which is the portal, application platform, and document collaboration aspect. This would be similar to how many businesses use their Windows servers: simple file shares for most shared files, and SharePoint for documents where advanced collaboration features are needed.

In the meantime, it is a mess, and with the explosive growth of Office 365, a tricky one to resolve without pain.

Microsoft has a relatively frank FAQ here.

Postscript: here is a tip if you need large amounts of OneDrive storage. If you buy Office 365 Home for £7.99 per month or £79.99 per year (which works out at £6.66 per month) you get 1TB additional storage for consumer OneDrive for up to 4 users, as well as the main Office applications:

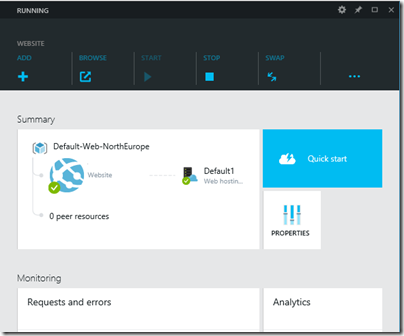

The way this works is that each user activates Office using a Microsoft account. The OneDrive storage linked to that account gets the 1TB extra storage while the subscription is active.

Another option is Office 365 Personal – same deal but for one user at £5.99 per month, or £59.99 per year (£4.99 per month).

Even for one user, it is cheaper to subscribe to Office 365 Home or Personal than to buy 1TB storage at £3.99 per month per 200GB. When you add the benefit of Office applications, it is a great deal.

Despite the name, these products have little to do with Office 365, Microsoft’s cloud-hosted Exchange, SharePoint and more. These are desktop applications plus consumer OneDrive.