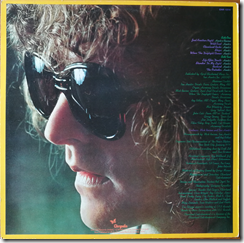

You’re never alone with a Schizophrenic (May 1979)

Chrysalis CHR 1214

UK: 49. US: 35

Overnight Angels, you will recall, was meant to be a hit album after Ian Hunter returned to a more traditional approach with rockers and ballads, as opposed to the jazz-tinged, quieter and more thoughtful All American Alien Boy. Overnight Angels was also the name of the new band. It flopped though, not least because Columbia did not even release the album in the USA. In June 1977 Ian Hunter’s Overnight Angels did a short UK tour. “I hated the whole mess I was in,” recalls Hunter, quoted in Campbell Devine’s biography. “I knew I was writing sh-t, singing sh-t, and playing sh-t.”

Next up was some work with Corky Laing of Mountain, first a session of demos for a projected new LP followed by a further session with Mick Ronson, Laing, and John Cale, and another session at Bairsville Studios with Todd Rundgren producing (see The Secret Sessions as mentioned above), but nothing came together commercially.

This brings us to 1978. Hunter was at a bit of a loose end. He produced an album called Valley of the Dolls, by Generation X, which put him in touch with the album’s label Chrysalis Records. Chrysalis offered Hunter a recording contract, so Hunter got back together with Mick Ronson and work started on a new album. In January 1979 work started in earnest at the Power Station in New York. The band was formed by Ronson along with three members of Bruce Springsteen’s E Street band: Roy Bittan, Gary Tallent and drummer Max Weinberg. Bittan had also worked with David Bowie on the 1976 Station to Station album, continuing Hunter’s habit of borrowing ex-Bowie sidesmen. The new album was provisionally called The Outsider. Engineer was Bob Clearmountain. The album came together quickly and Hunter has great memories of the recording experience. “That album was people getting down to business and really working hard … the E Streeters were all extremely nice people, nothing was too much trouble.”

The title was changed to You’re Never alone with a Schizophrenic, taken apparently from some graffiti spotted by Ronson.

Despite the polished result, it was not a big budget album. Hunter has some recollections here [http://www.songwriteruniverse.com/ian-hunter-interview-2017.htm]:

“For Schizophrenic it was a new studio, there was a new engineer Bob Clearmountain, who later went on to fame (mixing Bruce Springsteen, the Rolling Stones and many other artists). Bob had just worked with Chic and he was fed up with doing disco. But he had great drum sounds. And we were in the Power Station (studio), which was then kind of a disco place.

"I had started in London, with people like Glen (Matlock) from the Sex Pistols…people like that…punk music. It didn’t sound too good. At the time, my manager Steve Popovich said, “the E Streeters will [play on the album] if you want to come back (to the U.S.) and do it here.” So we did it with the E Streeters and Mick was with me. And we went into the Power Station and we wanted a bit of eerieness here and there, you know, so John Cale (of the band Velvet Underground) came in. It was all done pretty quick. The budget was small; it was the first record I did with Chrysalis.”

Just another night is a rocker whose lyric Devine says is based on the time in 1973 when Ian spent a night in an Indianopolis jail while on tour with Mott. “Oh no, the fuzz, all in a line – My oh my, I think I’m gonna die.” The song is good but not great; but you can immediately hear how well the band gels and what a great sound they achieved.

Next up is Wild East, about East Side New York, another energetic number that does not quite hit the heights but most enjoyable nonetheless.

Cleveland Rocks follows. “When we first came [to the U.S.], you had those talk shows like Merv Griffin and Johnny Carson, and I noticed that they’re always taking the mickey out (making fun) of Cleveland. If there was a town to be taking the mickey out of, it was Cleveland. And I’m like, “That’s not right. Because we didn’t get discovered in L.A., we didn’t get discovered in New York. We got discovered in Cleveland, as did a lot of people.” The same with (David) Bowie…Cleveland was way ahead. You’d play Cleveland and [the venue] would be full. Everywhere else, it would be like 150 people staring at you, saying “What is that?” And so that’s why I wrote “Cleveland Rocks.,” says Hunter in the interview also referenced above.

Who knows what is the full story of the song, which also had a life as England Rocks in reference to the punk movement, but *the song* certainly rocks, though it can be tiresome live.

Ships is the first ballad and it’s a great one, said to be about Hunter’s memories of his father. Great keyboard work from Bittan. “We walked to the sea, just my father and me, and the dogs played around on the sand.”

When the Daylight Comes is a cheery song though tinged with sadness, possibly another about a night with a groupie. “Sweet woman what’s your name? You smell as fresh as the rain … But when the daylight comes, I’ll be on my way.” The tone is upbeat though, with some striking lyrics: “I want to weave you in words, want to paint you in verse, want to leave you in someone else’s dreams.”

Life After Death seems like some of Hunter’s thoughts on religion, complete with a sort of church organ-y sound in the intro. It comes over though as more of a “live life to the fullest” type of song, an energetic rocker.

Standin’ in my Light kicks off a trilogy of songs which to my mind are what makes this album great. This song and the one that follows are probably related to Hunter’s distaste for Tony Defries, Bowie’s manager whom Hunter blamed for preventing him from working with Mick Ronson after the release of their first album together. Rock stars often struggle with their managers and other hangers-on; and Hunter is quoted by Devine saying that after the Overnight Angels debacle he refocused his life and “started with Standing in my Light, right in the middle of when I was getting clean of everyone.”

The lyric is strong. “Well I finally found you out, All through your mess of dreams … But you ain’t no pretty sight, And you’re standing in my light.” The organ drones, the guitar wails, and Hunter sings with real feeling.

As he does on the next one, Bastard. This is where Hunter lets rip. “You twist me til I’m lame, then you spin the coin again – you’re such a bastard.” What a great song though. It builds from a pounding beat, the guitar comes in, then Hunter delivers one of his best vocals.

Hunter says Bastard is a love song. In Campbell Devine’s book:

Asked to whom the lyric was addressed, and assuming it was a male, Ian replied, ‘It’s a she actually!’"

So that supports the love song idea. And the lyrics do seem to be addressed to a woman, if the transcription here is roughly right. "Vestal Virginia," ha ha.

And the rap at the end is good-humoured, suggesting that the song is playful rather than vengeful, though the lyrics have plenty of bite.

Hmmm, some sort of thrill of pain stuff here perhaps.

The Outsider closes the album. Ostensibly about a man on the run after killing a man in some sort of brawl, it conveys a powerful sense of life on the outside of society norms. No doubt too it has an autobiographical touch, not that Hunter ever “Just killed a man in a town called Nightfall,” but more that he’s a Brit in New York, he’s always on tour, he feels like an “outsider” much of the time.

Overall this is just a wonderful album; the band is superb, the songs are powerful, drawing on Hunter’s frustrations after a difficult couple of years, and the partnership with Ronson is up and running again, and better than ever.

The best Ian Hunter album? Well, it’s this one or Alien Boy. Or possibly one of the many albums to follow …