Yesterday NVIDIA announced the Geforce GRID, a cloud GPU service, here at the GPU Technology Conference in San Jose.

The Geforce GRID is server-side software that takes advantage of new features in the “Kepler” wave of NVIDIA GPUs, such as GPU virtualising, which enables the GPU to support multiple sessions, and an on-board encoder that lets the GPU render to an H.264 stream rather than to a display.

The result is a system that lets you play games on any device that supports H.264 video, provided you can also run a lightweight client to handle gaming input. Since the rendering is done on the server, you can play hardware-accelerated PC games on ARM tablets such as the Apple iPad or Samsung Galaxy Tab, or on a TV with a set-top box such as Apple TV, Google TV, or with a built-in client.

It is an impressive system, but what are the limitations, and how does it compare to the existing OnLive system which has been doing something similar for a few years? I attended a briefing with NVIDIA’s Phil Eisler, General Manager for Cloud Gaming & 3D Vision, and got a chance to put some questions.

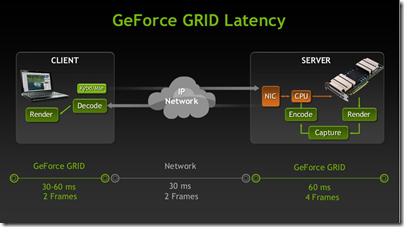

The key problem is latency. Games become unplayable if there is too much lag between when you perform an action and when it registers on the screen. Here is NVIDIA’s slide:

This looks good: just 120-150ms latency. But note that cloud in the middle: 30ms is realistic if the servers are close by, but what if they are not? The demo here at GTC in yesterday’s keynote was done using servers that are around 10 miles away, but there will not be a GeForce GRID server within 10 miles of every user.

According to Eisler, the key thing is not so much the distance, as the number of hops the IP traffic passes through. The absolute distance is less important than being close to an Internet backbone.

The problem is real though, and existing cloud gaming providers like OnLive and Gaikai install servers close to major conurbations in order to address this. In other words, it pays to have many small GPU clouds dotted around, than to have a few large installations.

The implication is that hosting cloud gaming is expensive to set up, if you want to reach a large number of users, and that high quality coverage will always be limited, with city dwellers favoured over rural communities, for example. The actual breadth of coverage will depend on the hoster’s infrastructure, the users broadband provider, and so on.

It would make sense for broadband operators to partner with cloud gaming providers, or to become cloud gaming providers, since they are in the best position to optimise performance.

Another question: how much work is involved in porting a game to run on Geforce GRID? Not much, Eisler said; it is mainly a matter of tweaking the game’s control panel options for display and adapting the input to suit the service. He suggested 2-3 days to adapt a PC game.

What about the comparison with OnLive? Eisler let slip that OnLive does in fact use NVIDIA GPUs but would not be pressed further; NVIDIA has agreed not to make direct comparisons.

When might Geforce GRID come to Europe? Later this year or early next year, said Eisler.

Eisler was also asked about whether Geforce GRID will cannibalise sales of GPUs to gamers. He noted that while Geforce GRID latency now compares favourably with that of a games console, this is in part because the current consoles are now a relatively old generation, and a modern PC delivers around half the latency of a console. Nevertheless it could have an impact.

One of the benefits of the Geforce GRID is that you will, in a sense, get an upgraded GPU every time your provider upgrades its GPUs, at no direct cost to you.

I guess the real question is how the advent of cloud GPU gaming, if it takes off, will impact the gaming market as a whole. Casual gaming on iPhones, iPads and other smartphones has already eaten into sales of standalone games. Now you can play hardcore games on those same devices. If the centre of gaming gravity shifts further to the cloud, there is less incentive for gamers to invest in powerful GPUs on their own PCs.

Finally, note that the latency issues, while still important, matter less for the non-gaming cloud GPU applications, such as those targeted by NVIDIA VGX. Put another way, a virtual desktop accelerated by VGX could give acceptable performance over connections that are not good enough for Geforce GRID.